1 Socioeconomic inequalities in

health in Europe

An overview

Johan P. Mackenbach, Martijntje J. Bakker, Anton E. Kunst and Finn Diderichsen

Introduction

At the start of the twenty-first century all European countries are faced with substantial socioeconomic inequalities in health, and it is the purpose of this chapter to briefly review the empirical evidence from around Europe. Such evidence relates to both the size and the nature of these inequalities and to their explanation, and is intended to lay the foundation for later chapters in this book.

Historical evidence suggests that socioeconomic inequalities in health are not a recent phenomenon, but it is only relatively recently, during the nineteenth century, and on the basis of mortality statistics, that socioeconomic inequalities in health were ‘discovered’. Before that time socioeconomic inequalities in morbidity and mortality went unrecognized, and there was even a general perception that all human beings were equal before death (1). In the nineteenth century, however, great figures in public health, such as Villermé in France, Chadwick in England and Virchow in Germany, devoted a large part of their scientific and practical work to the issue of socioeconomic inequalities in health (2–4). This was made possible by the availability of national population statistics, which permitted the calculation of, for example, mortality rates by occupation or by city district.

Since the nineteenth century the magnitude of socioeconomic inequalities in mortality has certainly declined in absolute terms: owing to the general decline in mortality the absolute difference in mortality rates between those with a high and those with a low socioeconomic position has become much smaller. It is less clear whether relative inequalities in mortality have also declined over time: relative risks of dying for those in a low rather than a high socioeconomic position have remained remarkably stable. During the past few decades there has even been a clear increase of relative inequalities in mortality in many developed countries (5–11). As a consequence, at the end of the twentieth century socioeconomic inequalities in health were seen by some as the biggest public health issue (12).

In the meantime, the emphasis of research in the area of socioeconomic inequalities in health has gradually shifted from description to explanation, and although the number of countries for which the results of explanatory studies are available is still limited, a general understanding of the factors involved has emerged. Childhood circumstances, material factors, health-related behaviours and psychosocial factors have all been shown to contribute significantly to the explanation of socioeconomic inequalities in health (13–17). A better understanding of this explanation has also laid the foundation for a systematic development of strategies to reduce such inequalities (18–20).

For the purpose of this book, socioeconomic inequalities in health will be defined as systematic differences in morbidity and mortality rates between individual people of higher and lower socioeconomic status to the extent that these are perceived to be unfair. In the literature on health inequality there is, unfortunately, no agreement about the way to conceptualize socioeconomic position. As in the sociological literature the choice is mainly between concepts of ‘class’ and ‘status’. Concepts of social class are based on theories of society, such as the Marxist theory of exploitation or the Weberian theory of market mechanisms creating inequality in access to resources. Concepts of socioeconomic status try to capture overall welfare along several dimensions of inequality but generally have no theory of the political and economic forces generating inequality attached to them (21). Measures of socioeconomic status might therefore be better predictors of health, as they better describe the material and behavioural conditions of individuals that are important causes of disease. For purposes of health inequality analysis it might nevertheless be more useful to think about socioeconomic position as defined by a theory of society rather than a theory of disease causation. The reason for this is that through such a definition, inequality in health is explicitly linked to a theoretical understanding of the societal mechanisms ‘upstream’ in the causal pathways.

Positions in a social structure should be distinguished from the individuals occupying those positions (21). Socioeconomic positions are defined by their function in that specific society’s division of labour, and have attached to them a number of characteristics of importance for health, such as power, working conditions and income. The health effects attached to a given socioeconomic position can be understood, however, only when they are analysed together with the biological, mental and behavioural characteristics of the individual who occupies it. The allocation of individuals to socioeconomic positions is strongly selective with regard to education, age, gender, race and health. The health distribution we observe across socioeconomic positions is the final outcome of all those effects and processes on health.

Socioeconomic inequalities in morbidity and mortality in

Europe

Before we present some summary data on socioeconomic inequalities in health, it is useful to look at some general indicators of health and socioeconomic development in Europe.

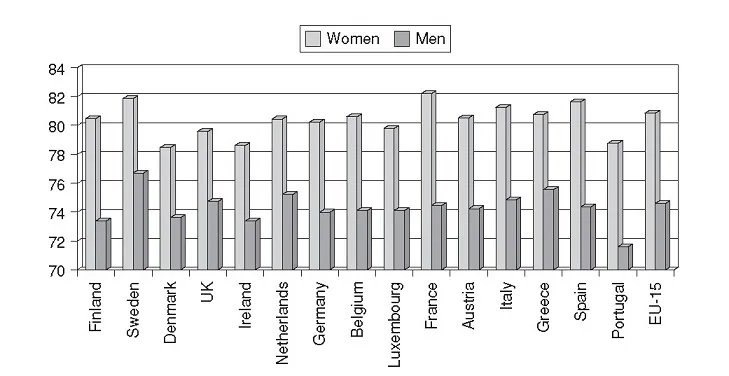

Figure 1.1 Life expectancy (in years) at birth: women and men (1997)

Source: Eurostat Yearbook 2000 (96)

In 1997, life expectancy for women living in the European Union (EU) was 81 years and for men approximately 5 years less (Figure 1.1). There were no clear differences between countries in the north and the south with regard to life expectancy. Life expectancy for women was highest in France and Sweden and lowest in Denmark, Ireland and Portugal.

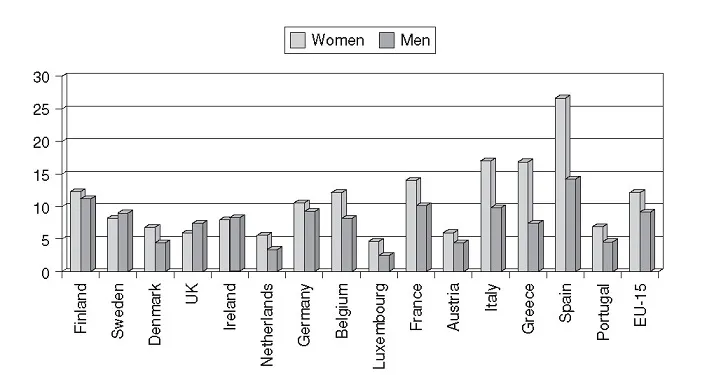

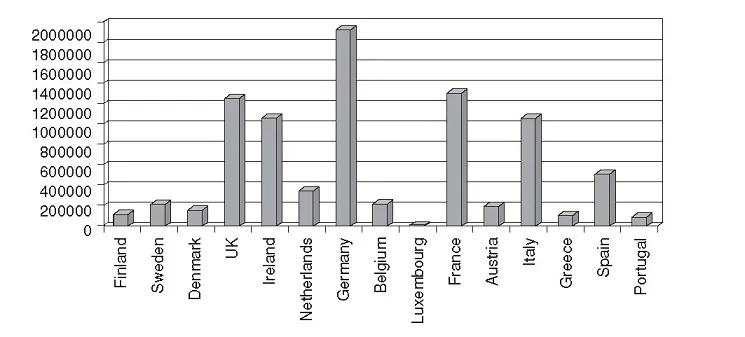

In 1998 the average unemployment rate was 12 per cent for women and 9 per cent for men (Figure 1.2). Unemployment rates for women were particularly high in Spain, Italy and Greece, and for men in Spain, Finland and France. In general, gross domestic product was higher in countries in the north of Europe than in those in the south (Figure 1.3), indicating more prosperity in the north of Europe. Furthermore, income is generally more unequally distributed in countries in the south of Europe (Table 1.1).

Socioeconomic inequalities in morbidity

Many countries have health interview, level of living or multipurpose surveys with questions on both socioeconomic status (education, occupation, income) and self-reported morbidity (for example, self-assessed health, chronic conditions, disability). Analysis of these data shows that inequalities in self-reported morbidity are substantial everywhere, and nearly always in the same direction: persons with a lower socioeconomic status have higher morbidity rates (22–25).

A comparative study covering 11 countries in Western Europe showed that in the mid-and late 1980s the risk of ill-health was 1.5–2.5 times higher in the lower half of the socioeconomic distribution than in the upper half. Substantial inequalities in health were found in all countries participating in this study, from Spain to Finland and from Great Britain to Italy. Surprisingly, substantial inequalities in self-reported morbidity were also found in the Nordic countries, despite their long histories of egalitarian socioeconomic and healthcare policies (26, 27). During the mid-and late 1980s, similar results were found in Central and Eastern Europe: for example, in the Czech Republic, Estonia and Hungary socioeconomic inequalities in self-reported morbidity are about equal to those in most Western European countries (28).

Figure 1.2 Unemployment rate (in percentages) of women and men (1998)

Source: Eurostat Yearbook 2000 (96)

Note: The Eurostat unemployment rates are calculated according to the recommendations of the 13th international Conference of Labour Statisticians organized by the International Labour Office (ILO) in 1982. Unemployed persons are those persons aged 15 years and over who are without work, are available to start work within the next two weeks and have actively sought employment at some time during the previous four weeks.

Figure 1.3 Gross domestic product at market prices current series in million ECU (1998)

Source: Eurostat Yearbook 2000 (96)

Table 1.1 Indicators of income distribution a in the EU, 1994

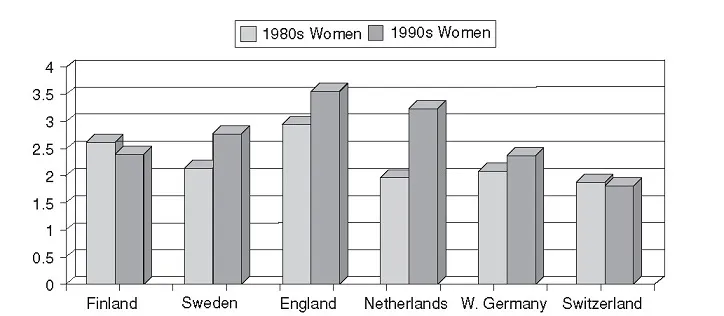

It is unclear whether socioeconomic inequalities in self-reported morbidity are increasing, stable or decreasing. Some studies have reported increasing inequalities, but a recent comparative overview of the situation in six Western European countries has shown that the picture is far from clear. The direction and magnitude of the changes seem to vary by country, socioeconomic indicator and type of health problem (29). The clearest patterns were seen for self-reported morbidity by income level, which has increased in a number of countries (Figure 1.4a and Figure 1.4b). Trends in the prevalence of ‘less-than-good’ perceived general health have been more favourable in the higher than in the lower income groups, and as a result inequalities have increased, adding to the urgency of the problem. Whether this rise reflects increasing income inequalities or the increasing economic consequences of illness due to changes in insurance systems, is unclear.

Figure 1.4a Odds ratio for...