- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Housing is something that is deeply personal to us. It offers us privacy and security and allows us to be intimate with those we are close to. This book considers the nature of privacy but also how we choose to share our dwelling. The book discusses the manner in which we talk about our housing, how it manifests and assuages our anxieties and desires and how it helps us come to terms with loss.

Private Dwelling offers a deeply original take on housing. The book proceeds through a series of speculations, using philosophical analysis and critique, personal anecdote, film criticism, social and cultural theory and policy analysis to unpick the subjective nature of housing as a personal place where we can be sure of ourselves.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Private Dwelling by Peter King in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArchitectureSubtopic

Architecture GeneralChapter 1

What is dwelling?

Ambiguity on purpose

Dwelling is a nebulous concept. It is one of those words we use in different ways, and to mean different things. We can talk of a dwelling or these dwellings, but also of the act of dwelling: we can talk of things and of actions. It is a word with a long history: Parliament passed several acts in the nineteenth century dealing with dwelling houses for the poor. It has a distinct biblical context: Yahweh, the God of the Old Testament, dwelt in the Ark of the Covenant and later in the Temple in Jerusalem. The word is also used in a technical sense, to define a residential property.1 There is then a difficulty in defining a word that is used in so many different ways.

Yet this very ambiguity might be useful to us. First, it points to the ubiquity of the thing underlying the concept: dwelling might be important if it is found so frequently in different contexts. Second, it might allow us to connect up what would otherwise be seen as incongruent areas, such as the theological with the architectural. As we shall see throughout this book, we need a concept that allows us to draw from many areas, as this is precisely how we lead our lives. We are concerned at times with matters theological and at other times with the plumbing. This may appear flippant, yet our lives do shift from the mundane to the sublime, and we need both a receptacle and a conceptual frame in which to unite them. Third, a lack of precision allows different meanings and emphases to be elided together into something that still retains some general meaning. So it is useful to say that we all dwell, yet our particular dwellings differ markedly. Modern Europeans live differently from Bedouins, and from our ancestors a thousand years ago; I do things differently from my neighbour, and my wife does things differently from me. This is just as it should be. Yet we are all doing, at the most general level, the same thing. Dwelling allows this generality to be said.

What is fascinating about dwelling is not just its ambiguity, but the fact that it operates between two poles – the ubiquitous and the specific: the mundane and the unique. Dwelling is something we all experience, but it is not something that we necessarily experience together. For each of us dwelling is unique, in that it is something we do by and for ourselves. We all dwell, but each of us does it separately.

It is this ambiguity that I am most interested in and wish to explore in these speculations. However, I wish to be somewhat narrower in my discussions than the concept of dwelling would otherwise allow. Whilst I shall offer a fuller definition of dwelling in this chapter, this is only to give full resonance to the term and to put my main topic into focus. My priority is to consider how we dwell privately, and hence I am particularly concerned in this apparent dichotomy between the mundane and the unique: between the fact that dwelling is something we all do, and the counter fact that how I experience dwelling is different from how others experience it, including to an extent those with whom I share my dwelling. What I wish to consider then are two key epistemological questions to do with dwelling. First, how do we respond to the physical box we call the dwelling? In others words, what is the relationship with the physical entity of a dwelling? The second question is, how do we regard this relationship: what significance do we give to it, and in what sense or senses does it transcend the physical? In short, why it is so important to us on a number of levels?

Yet, answers to questions such as these that can be framed in different ways, and which themselves depend on other questions, are likely to prove illusive, and such an illustration is offered in a wonderful quote in David Schmidtz’s book on Robert Nozick. He is discussing the idea of philosophy as persona in relation to Nozick’s frequently misunderstood book, The Examined Life (1989). Schmidtz states that ‘Life is a house. Meaning is what you do to make it a home’ (Schmidtz, 2002, p. 212). This simple statement, which does not quite veer into sentimentality, makes clear the distinction between objects and subjects: between things that allow us to do and be, and doing and being itself. But this quote is also useful for connecting dwelling with a more general sense of how we live. We seek to do meaningful things and most things are meaningful because of what we do. Dwelling is that activity that contains this meaning, but what we do it in is a dwelling.

Yet, we need to remember that policy makers and professionals do not talk about dwellings, nor do they concern themselves any more with housing: they are concerned with homes. Both private developers and social landlords build homes and not houses; for them there is only one level, with any nuance between dwelling, house and home occluded into the one entity.

But the problem goes deeper. Not only is it one of misdescription, but also it ignores that the full functions and uses of dwelling cannot be created by housing policy. Policy can only achieve the basics – the brick boxes – and even there it may fail. Indeed it is hard to see what role any public agency can play other than to provide enough brick boxes and ensure people can afford them. Of course this is not a particularly negligible role – we can do little unless the dwellings are there first – but it is still a limited one. The problem is that politicians, policy-makers and practitioners either do not appreciate this or simply refuse to accept it.

But there is a further thing they refuse to accept: that dwelling can actually be impeded by policy. This is usually a result of the introduction of policy into areas where it is not applicable, where housing practitioners are not, and cannot be, expert. This is the level of relationships within and outside the dwelling: with how we use our housing. Outside interference will either be arbitrary, based on the whim of the person intervening, or overly standardised, as a result of a general policy. But it can be no other: there is no possibility of policy or even an individual practice being so fine-grained as to actually articulate the varied needs and choices of all, or even many, households. Housing policy should then restrict itself to the provision of brick boxes and leave what goes on inside them to the users.

Housing policy does not, because it cannot, engage with how we live. There is little it can do about how we use housing, without destroying that use through its interventions. Rather policy should be concerned merely with the ‘what’ and the ‘where’: with production and standards, access and control. These are important issues, but there is something equally important missing from the totality of housing as a practice. This gap is to do with the subjective – with the individualised, personal relationships that we have with our dwelling. Once a dwelling has been built it remains a mere thing. Only when it is occupied does it take on a meaning and significance beyond this physical structure: only then, so to speak, does the house become meaningfully a home.

But just what is it that our housing does for us? What functions does it perform? What does it allow us to do? Now most assuredly, these are questions capable of a glib response. Houses are for living in, aren’t they? They provide shelter and security. We might suggest that housing is related to status and social value, and thus we can use tenure and style (detached or semi-detached, terrace or mews, single or double garage, and so on) as measures of success. Like all glib answers, these contain within them an element of common sense and speak at least a partial truth. So, of course, houses are for living in; they do help to make us secure and safe.2 But glibness will only take us so far. Our relations with and within our housing are complex and multi-dimensional. What is more, these relationships differ from person to person. Therefore glib answers, because they seek an instant judgement, miss many of the nuances and subtleties of our lived experiences within dwellings. One can submit to glibness because of the very ubiquity of dwelling – we all do it and we all know what it does or ought to consist of. Yet the superficiality of our scepticism is evident as soon as we start to consider what it actually is that we do. It is the very subjectivity of this common relationship, with its self-generated aims and interests, that brings us up sharply against a dilemma.

What is needed therefore is a more considered answering of the basic questions concerning the use of housing and its significance. What we need is some mechanism whereby we can unpick the complexities of dwelling as a subjective experience. This can be achieved, I believe, through a consideration of descriptions of dwelling and the use of these descriptions in particular situations. What is sought, therefore, are those universal notions of significance common to all dwellings that can be derived from a close analysis of lived experience, to draw out the concepts upon which the significance of housing is made manifest. These studies need to be specifically based on actual activities within dwelling. As such, we need to consider concepts such as privacy, sharing, the way we describe and discuss where and how we live, our desires for it and within it, and the anxieties that go along with possession and yearning. This is what these speculations seek to explore, not in any definitive or prescriptive manner, but to open up dwelling as a place of possibility and enquiry free from the dictates of policy and practice. But first, dwelling needs to be defined more fully. A precise definition is neither possible nor wanted – it would limit possibilities – but we do need to be clearer about what it is we are describing.

The phenomenology of dwelling

Housing is more that mere possession. It facilitates or restricts access to employment, family, leisure, and the community at large. This is partly a question of affordability and location, but it also relates to notions of identity, security and the significance of place. What determines how we view housing, therefore, is how we dwell. This shows immediately that there is a distinction between housing and dwelling. Indeed housing, properly speaking, is a subset of dwelling. Dwelling encloses housing, but much more besides. But this is to get ahead of ourselves. We need first to look at these two notions at a more basic level.

Both the terms are ambiguous, partly because they can be used as a noun and a verb. However, there is a distinct qualitative difference between the two terms. Housing, as a noun or verb, cannot be separated from the physical structures called houses. It is, of course, the collective noun for these entities. But even the activity of housing is limited to management and control of these physical structures. However, we can see dwelling as meaning far more than the general physical space meant for personal accommodation. To dwell means to live on the earth and can refer to diverse activities such as human settlement, the domestication and taming of nature, and the creation of permanent social and political structures (markets and urban space) as well as the private inhabitation of space (Norberg-Schulz, 1985). Tim Putnam (1999, p. 144) believes ‘Dwelling is at the core of how people situate themselves in the world’. Dwelling is where human beings inhabit space in the broadest sense. It collects up physical and broad sociological factors but also those psychological, ontological and emotional resonances we experience within the context of our personal physical space.

But we need to make a further distinction between the two terms. Inasmuch as housing relates to, and is inseparable from, physical objects, many of the concepts we connect with our dwelling, such as privacy, security and intimacy, are intangibles. These are not things we can touch, but we experience them, as it were, as by-products of the relationship between our dwelling and ourselves. It is not the dwelling that gives us these things of itself, but the manner in which we are able to use it and how it relates to a wider series of meanings.

Dwelling has a public and a private dimension. Christian Norberg-Schulz (1985) makes this distinction by differentiating the public dwelling of institutions and public buildings and the private dwelling of the individual house. Likewise, he recognises that the process is undertaken by the community at large and the individual household. Such a distinction is derived from the later thought of Martin Heidegger, in particular his essay ‘Building, Dwelling, Thinking’ (1971). In this essay Heidegger equates dwelling with building: for humans to dwell means they build structures for themselves. In turn, he defines building, through its etymological roots in Old English and German, as related to the verb ‘to remain’ or ‘to stay in place’ (p. 146). Dwelling as building is thus more than just mere shelter, but is a reference to the settlement by human beings on the earth. Indeed for Heidegger, dwelling is humanity’s ‘being on the earth’ (p. 147). Heidegger is prepared to see dwelling in the broadest sense, as human settlement in general. Dwelling is the house, the village, the town, the city and the nation in their generality – it is of humanity taking root in the soil.

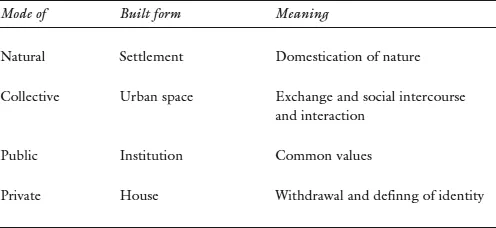

Norberg-Schulz takes Heidegger’s phenomenological approach and extends it into a discussion of the meaning and nature of dwelling which is both more thorough and less metaphysical than Heidegger’s description. According to Norberg-Schulz, dwelling refers to spaces and places, both in terms of how they are used and what this use means to individuals and communities. Dwelling, he suggests, means three things. First, it involves meeting others for the exchange of products, ideas and feelings, where we experience life as a multitude of possibilities. Second, dwelling means to accept a set of common values. It is through this that we can share. We dwell through establishing and operating conventions. Third, it is to be ourselves, where we have a small chosen world of our own: it is our private place where we can withdraw from the wider world. These three meanings are, of course, interrelated. We are able to be ourselves through the security of a common bond within a community of like individuals able to freely meet and exchange. Norberg-Schulz recognises this when he states that, ‘When dwelling is accomplished our wish for belonging and participation is fulfilled’ (1985, p. 7). Thus an important linkage between the public and the private is enacted through dwelling. The security of dwelling gives us the ability to participate within the community. Dwelling identifies the individual with the community, using place as the reference: ‘The particular place is part of the identity of each individual and since the place belongs to a type, one’s identity is also general’ (p. 9). In stressing this linkage between the public and the private Norberg-Schulz is recognising the crucial sense of dwelling whereby we are part of a place and that place is part of us. He goes on to define four modes of dwelling which show the extensive nature of this concept (see Table 1.1).

Dwelling consists of a series of connections, a mix of public and private space

First, he describes the idea of ‘settlement’. This is the mode of ‘natural dwelling’, where humans develop, use and exploit the natural environment. We can equate this to the process of the domestication of nature and its subsequent development as a predeterminant of stable civilisations (Hodder, 1990). Accordingly, we can add the domestication of nature to the three meanings already stated by Norberg-Schulz. Second, he describes the mode of ‘collective dwelling’, where human interaction takes place in the medium of urban space. This is where the first meaning of dwelling is fulfilled, as people interact to exchange products, ideas and feelings in towns and cities. Third, Norberg-Schulz defines the mode of ‘public dwelling’. This is the forum where the common values, as articulated in his second meaning of dwelling, are expressed and kept. He identifies this mode of dwelling with the institution, be it political, social or cultural. Finally, he defines the mode of ‘private dwelling’, as exemplified by the house. This is where we are able to be ourselves. It is ‘a “refuge” where man gathers and expresses those memories which make up his personal world’ (p. 13). This, then, is where we can withdraw from the world to define and develop our own identity. Norberg-Schulz’s conceptualisation of dwelling is able to encompass historical, philosophical, psychological and social dimensions. In so doing, he demonstrates the nature of the ‘belonging and participation’ which dwelling brings. He shows how dwelling is the security (private dwelling) to participate in, and withdraw from, a stable agreed culture (public dwelling) where social interaction (collective dwelling) is facilitated within, and co-determined by, our environment (natural dwelling).

Table 1.1 A taxonomy of dwelling

Norberg-Schulz goes on to consider the meaning that dwelling gives, and is given by, the individual and the community. He does this through the articulation of two concepts, identification and orientation. Identification is to experience a ‘total’ environment – where the four modes considered above are present – as meaningful for what it is. He is here associating dwelling with the phenomenological concept of the lifeworld. This concept, as initially defined by Edmund Husserl (1970), refers to the meaningful world of things into which individuals are born. Husserl suggested that the lifeworld can be seen as a series of overlapping circles, beginning with the homeworld, and rippling out into the social world. The lifeworld then consists of those things that surround each person, yet are implicitly accepted without conscious thought. David Pepper (1984) defines the lifeworld as the world of familiar ideas, experiences and objects, like the furniture, ‘on which we do not consciously bring to bear our thought processes but in whose sudden absence we could feel disturbed, as if something were wrong’ (p. 120). We only recognise this lifeworld by thinking ‘consciously and descriptively about things we do not usually think of in this way in order to bring them from the back to the forefront of cognition, and make explicit what was implicit’ (p. 120). Short of their absence then, we must actively strive to recognise their significance; we identify with them only implicitly through their taken-for-granted presence. Pepper goes on however, ‘And since the “lifeworld” is a personal thing, varying from individual to individual, we cannot induce law-like statements about it’ (p. 120).

The notion of the lifeworld, and of identification, relates to Heidegger’s notion of things as being ready-to-hand (Heidegger, 1962). This is where a thing is transparent to consciousness provided it fulfils its prescribed function. The thing is equipment, an extension of the person using it, and thus unnoticed as present-to-hand, as a substance with distinct properties. The things which form our lifeworld therefore are equipment ready-to-hand. Only once there is a problem with them, so that they are unready-to-hand, do we become conscious of these things as present-to-hand, short of a conscious deliberate act of abstract thought to focus upon these things. We use the things around us as extensions of ourselves and...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- series

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Introduction Looking out and looking in

- 1 What is dwelling?

- 2 Privacy When dwelling closes in on itself

- 3 A brick box or a velvet case?

- 4 Talking about houses

- 5 Ripples Sharing, learning, reaching out

- 6 Want it, have it!

- 7 Fear and the comfort of the mundane

- 8 Loss

- The stopping place

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index