![]()

1

Conversations about Calling

“How does it make you feel?” “Does it have a positive impact on others?” “Does it turn up the volume and increase the vibration of your life?”1 Media mogul Oprah Winfrey posed those questions to help her readers gain insights about their “callings.” Contributing authors to the “Find Your True Calling”2 issue of O Magazine echoed the core themes embedded in her questions—personal alignment, intense emotions, prosocial intent, and something transcendent (e.g., vibration). Interestingly, these same themes dominate contemporary management scholarship—not surprising given that management scholars’ renewed interest in calling coincided with Winfrey’s ascent as an “arbiter of truth”3 during the 1990s.

Modern management scholars generally agree that a calling entails engaging in work that is intrinsically rewarding because it is aligned with one’s passion, core interests, abilities, and perceived destiny. Consequently, work in a calling is energizing, elicits commitment, and sometimes benefits society. Similar themes are evident in definitions of calling that guide management scholarship.4 More specifically, the Encyclopedia of Career Development states:

The idea of viewing one’s work as a calling came into common usage with Max Weber’s concept of the Protestant work ethic. While a calling originally had religious connotations and meant doing work that God had “called” one to do, a calling in the modern sense has lost this religious connotation and is defined here as consisting of enjoyable work that is seen as making the world a better place in some way. Thus, the concept of a calling has taken on a new form in the modern era and is one of several kinds of meanings that people attach to their work.5

This definition suggests that modern management has made considerable progress beyond historic theological notions of calling—but not all management scholars agree.6 Although encyclopedic definitions have the cache of authority and dominate the discourse, some management scholars contend that calling is still a transcendent or religious concept, but they are in the minority. The source of discord among management scholars can be traced to fault lines that frame conversations about calling. In this chapter, I explain the contours of those fault lines, resulting conversations about calling, and overall implications for calling scholarship and practice.

Fault Lines That Define Conversations About Calling

Calling is an old idea that found new life in management scholarship at the end of the 20th century. The conversation about calling is centuries old and has spawned multiple conversations as religious adherents, philosophers, social scientists, and cultural trends have influenced its meaning. New actors and epochs have spawned revolutionary changes in the meaning of calling and evolutionary changes7 that reflect incremental shifts in our understanding and its application.

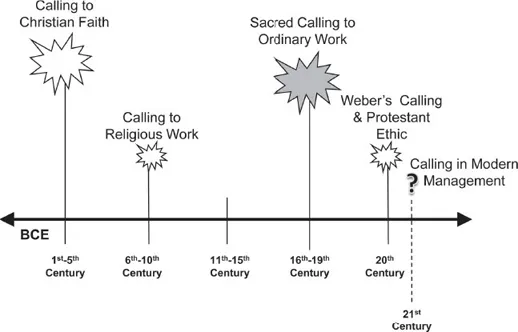

Three historical epochs carved fault lines that now define calling scholarship: (1) the Protestant Reformation of the 1500s, which defined calling as a sacred approach to ordinary work; (2) the simultaneous birth of management studies and the introduction of calling into it in the early 1900s; and (3) renewed interest in calling in the 1980s. These epochs are illustrated in Figure 1.1. Revolutionary changes in the meaning of calling are illustrated by large, dramatic flashes, while more incremental evolutionary changes are represented by minor flashes along a continuum from before the Christian era (B.C.E.) to the present.

Figure 1.1 Twenty centuries of revolutionary and evolutionary shifts in the meaning of calling.

Revolutionary conversations about calling originated with being called to the Christian faith after the ministry of Jesus Christ. Shortly thereafter, an evolutionary shift in meaning denoted calling as a summons to religious occupations and service.8 Sacred meanings of calling as religious service persisted for more than 1,500 years.

In the mid-1500s, a revolutionary shift occurred when Protestant Reformers Martin Luther and John Calvin appropriated the term calling and declared that all ordinary work was sacred, not just work in a monastery. For the remainder of the millennium to the present, theologians have continued to theorize, sermonize, and write about the sacred calling in secular life.9 (Theological perspectives of calling will be examined in Chapter 9.) As Figure 1.1 shows, there has been no widely accepted revolutionary shift in the meaning of calling since the 1500s; truly revolutionary changes are both rare and disruptive.

The next notable evolutionary shift in meaning occurred nearly 500 years later, when calling was catapulted into management studies at the dawn of the 20th century. The issue that interests us here is whether modern management’s perspective of calling in the 21st century is best described as revolutionary, evolutionary, or something else.

Origins of Calling in Management Studies

Renowned sociologist Max Weber introduced the idea of calling to the nascent discipline of organization studies in the early 1900s with his book The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism10 (hereafter Weber). His ideas about calling were evolutionary in the larger context, but injecting calling into the new field of management studies was indeed revolutionary for management. Weber referred to the theological writings of Protestant reformers Martin Luther and John Calvin to describe calling as a “peculiar ethic” that infused ordinary work with religious or sacred meaning. He hypothesized that a sacred calling resulted in highly motivated employees who approached work in ways that “enormously increase performance,” thereby contributing to remarkable economic growth. Intrigued by these ideas, industrialists and clergy experimented with integrating spirituality and work during this era, which I examine in Chapter 9. Yet, Weber was concerned that the robust religious construct might become a ghost of its former self in the new economic system—with good cause.

Weber considered religion an important dimension of modern life in the industrial age, as did his contemporaries, psychologist William James and sociologist Emile Durkheim. Yet Weber’s perspective was eclipsed by two academic trends—Scientific Management and positivism. Frederick Taylor’s book The Principles of Scientific Management,11 was the cornerstone of management studies and was published shortly after Weber’s book. Scientific management sought to enhance employee performance with exhaustive measurement—not meaning and motivation. Taylor used time and motion studies to measure and improve observable work practices, which resonated with industrialists and managers. Moreover, Taylor’s techniques were validated by the second academic trend—positivism in scientific research.

Positivists, and logical positivists, measure what is distinctly observable. The goals of positivist approaches to research are to identify and predict cause-and-effect relationships in order to control those causes and outcomes. This research tradition seeks to verify or falsify claims or deem them meaningless. However, since metaphysical, spiritual, and religious constructs are not easily observable, knowable, or verifiable, they were not considered “serious” topics for social science research in that era.12

Positivism prevailed from the 1920s to the 1950s, coinciding with management’s Human Relations movement of the 1920s−1940s, when psychologists redirected their attention from time studies toward human need; indeed, careerism and fitting a person with his or her environment (i.e., Person-Environment [P-E] fit) followed.13 As these ideas prevailed, Weber’s calling receded in importance and lay dormant for decades.14 Calling was a dead topic in management during most of the 20th century.

It stands to reason that in 1968, when calling reemerged in management scholarship—having been filtered through Taylorism and positivism—that the definition was quite different from Max Weber’s original idea. Richard Hall resurrected calling with a study of professions and bureaucracy during the ascent of careerism. Hall’s definition reflected the prevailing academic zeitgeist: “A sense of calling to the field—this reflects the dedication of the professional to his work and the feeling that he would probably want to do the work even if fewer extrinsic rewards were available.”15 Hall’s assertion is notable because he decoupled calling from religion, God, and sacred notions of work. Further, he tightly coupled calling and career by associating it with professions (e.g., law, medicine, and accounting).

Nearly 20 years later, in 1987, Phillip Schorr published an article about public service as a calling,16 in which he defined calling as “joyous service” to a profession. Having traced the origins of calling from ancient Greece to the Bible to Weber, Schorr believed that the utility of calling could be increased by disconnecting it from religion and making it broadly applicable to non-religious endeavors such as public service and administration. He asked, “Can we promote the contemporary equivalent of the calling by creating commitment and passion for the public service by means of an administrative theology?”17 Apparently, Schorr was unaware that reformers’ revolutionary idea of calling applied to non-religious endeavors and was broadly applicable to all work. For Schorr, an “administrative theology” had more practical utility than an actual theology of work, as Weber suggested. (I discuss the risks of an administrative theology in Chapters 8 and 9.)

The 1980s publication that had the greatest influence on management thought about calling was Habits of the Heart,18 by Robert N. Bellah, Richard Madsen, William M. Sullivan, Ann Swidler, and Steven M. Tipton (hereafter Habits). Habits emphasized the importance of institutions in strengthening community and society as a means of moderating the rise of expressive individualism, which is characterized by strong feelings, rich sensual and intellectual experiences, self-expression, and luxuriating in one’s interior world.19 In Habits, the authors did not dismiss religious notions of calling as Schorr did; instead, they suggested that it had been weakened and displaced, which is precisely what Weber feared. Thereafter, calling became an intriguing topic in management, and publications proliferated.

Given the trajectory of calling scholarship in management, it is “logical” that the dominant conversation asserts that calling is a secular orientation toward occupational work. If this is true, however, the notion would represent the first revolutionary shift in meaning in 500 years! While some might think it’s about time, and it may be, not reflecting on the context, causes, and consequences of such a momentous change is intellectually reckless. So, I consider them here.

The Revival of Calling in Historical Context

Each epochal shift in the definition of calling to date—from the call to religious belief and behaviors, to a call to religious service, to the sacred call to ordinary work—has added layers and texture to its meaning, making calling more robust and relevant ...