- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

For the first time, this book brings the insights, methodologies and visions of film to the practice of architecture.

Walls Have Feelings poses unanswered questions from our immediate past, crucial for the future of the city: what was the cultural mindset leading to the triumph of Brutalism? What is the urban and domestic impact of large scale office building? Are there alternatives to the planners' city of object? and, Why does your flat leak?

This book uniquely brings to bear questions of urgent cultural relevance on critical design decisions. As such, it is of as much importance to architects, planners and students of design, as to students of cultural history, geography and all enthusiasts of cities and of film.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Walls Have Feelings by Katherine Shonfield in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArchitectureSubtopic

Architecture GeneralPart one: The Detail

Chapter 1

How Brutalism defeated picturesque populism: parallels in film and architecture

It is hardly possible to overdramatise the effects that the wholesale adoption of the Brutalist style – with its trademark bleak, uncovered, grey concrete – has had on the landscape of London. Together with its architectural sister, system building, and the monuments of the office boom, the tower blocks and new housing estates have transformed our experience of the city.

This book starts with an attempt to shed light on a question still to be answered, and which remains as urgent today as much as in the aftermath of the 1960s. What made the British reject out of hand their traditions of gentle adaptation and picturesque embellishment, and take on so comprehensively an architectural style that was self-consciously ugly and ideologically generated? The reason for the continued urgency is an apparently never-ending schism between how the general public perceive the after-effects of Brutalism, and the immovable conviction by architects that this period was their heyday. For architects, this was both the last time the profession could transform the everyday lives of the many on a concerted scale; and also the last time a style had social and political purpose, imbued with architectural integrity. As for the public, they just hate it.

The fall-out persists into this century. Before the public can give any large-scale commitment again to architects, a line of mutual understanding has to be drawn under the circumstances which generated the styles and forms of this period.

To begin a new exploration in this chapter, I try to do two things. The first is to suggest that the defence (or otherwise) of the border is an overriding theme which allows an understanding of the interconnection of political, social, architectural and cultural activities in the decades preceding the 1960s. The second is to look for insights outside architecture, specifically in film, and to seeks parallels and commentary on the demise of the picturesque aesthetic in British cinema of the same period.

The picturesque architecture of the 1940s and early 1950s is currently enjoying new interest. Its most well-known example is the buildings of the Festival of Britain. This was a national festival put on six years after the end of war, in 1951, which temporarily occupied the area of the South Bank of the Thames directly opposite London’s West End. I consider this against the once again popular Ealing comedy, Passport to Pimlico. The Festival buildings embody what’s been seen either as a happy marriage or an abominable birth. They are the result of the fusion between two apparently opposed traditions: the rigours of international modernism and the English picturesque tradition, a tradition which implies design first and foremost in terms of the composition of a series of visual pictures.1 In film, I suggest, there was a broad, and perhaps equally popular equivalent: the Ealing comedy. These quintessentially English films emanated from the Ealing Studio in west London, and were at their best in this period. They epitomise the spirit of post-war Britain and London in particular: a hybrid world where there was a simultaneous longing for radical change and tangible continuity. As if to express this strange contradiction, the comedies feature gangs of lovable robbers, charming and funny murderers and, in the case of Passport to Pimlico, sensible and conventional anarchists.

Both architecture and film began to go markedly out of fashion in the second post-war decade. They were replaced with monochrome, and supposedly true-to-life genres: Brutalism’s parallel was Britain’s version of the New Wave in cinema.2 Angstridden, alienated loners replace chirpy communities. Remorseless realism replaces happy endings. This is both an exploration of parallels between their aesthetics and their preoccupations, and an attempt to cast insight from architecture on cinema and vice versa. The preoccupations of post-war architecture set the scene at the beginning of the chapter, and cinematic themes are taken up in the second half.

To allow speculation between the social, political architectural and filmic material, I use a fictional motif. It is extrapolated from the anthropologist Mary Douglas’ theory of the origins of pollution taboos. It is described in more detail in this book’s Endpiece. The point of using this work is to arrive at a kind of common currency which allows us to move between the various areas of exploration. As I indicated above, this concerns the idea of the defence of the border. Borders hold in what is defined and pure. And a set of characteristics allows identification of the pure in contrast to the hybrid. The pure can have a line drawn clearly round it. The pure can be reduced to an original set of classes. The borders between the form of the pure and the formlessness outside it, are well defined and self-evident.

The idea of the hybrid is the opposite of the pure. The hybrid straddles two or more classes; its edges are unclear, and difficult to delineate, to draw a line around. The hybrid doesn’t have an identifiable, categorisable form. The hybrid obscures the possibility of its reduction to an original set of parts or classes. The hybrid transgresses the edges of established forms. The pure and the hybrid polarise the two tendencies in British post-war architecture. And these two tendencies can be personified in two iconic buildings, the Skylon and Hunstanton School.

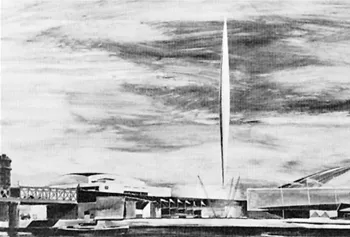

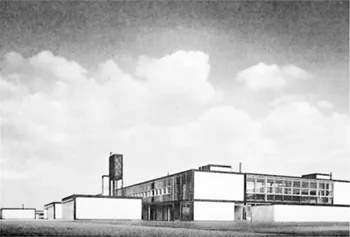

The Skylon (Fig. 1.1) was a vertical structure built for the Festival of Britain in 1950, and designed by two competition-winning architectural students, Philip Powell and Hidalgo Moya. Hunstanton School, another competition winner designed by Alison and Peter Smithson, was one of the first Brutalist buildings completed six years late, and crucial to Brutalism’s identification as a new and challenging style (Fig. 1.2).

1.1 Drawing by Hidalgo Moya of the Skylon, Festival of Britain, London (1951): Powell and Moya.

1.2 Hunstanton School, Norfolk, UK (1956) Alison and Peter Smithson

The presentation drawing shows the Skylon as part of a picturesque composition complete with moody sky, passing boat and Victorian railway bridge. It also shows that it is meant to be experienced as seamless. Skylon was clad in steel panelling but the edges between components are suppressed, the line between distinct constructional parts fuzzed. The structure connecting the Skylon to the ground is similarly made invisible. The structure seems to float intangibly: the point at its bottom end means it can never sit on the ground like a structure that could be categorised as ‘tower’. Skylon, like its equally popular post-war namesake, Nylon, is a hybrid.

By contrast, Hunstanton is pure. While it completely lacks what became the Brutalist tag, uncovered concrete, Hunstanton is a textbook of the characteristics behind the idea of this most self-conscious of styles. Hunstanton declares the distinct categories of its construction throughout. The edge is clearly underlined between brick panel and steel frame. It is equally clear that the frame not the bricks holds the building up. The purity of its form, expressed by the parts that make up the building, is as transparent from inside as it is from outside (Fig. 1.3).

No attempt is made to cover up any edge, or obscure any category. In this interpretation, Brutalism defends borders; it upholds the unpolluted and pure against the hybrid characteristics of the Festival Style.

The problem, though, as ever, is how to relate these specifically visual aspects of architecture to broader social and political ideas, that is, the context for these two markedly different ways of making buildings. Mary Douglas herself establishes terms which cross over from the material to the social. She characterises four varieties of social ‘pollution’, all associated with defence of the border. They are threats to external boundaries; threats to internal lines within a social system; threats to margins of the lines defining a social system; and the fourth variety is ‘danger from internal contradiction, when some of the basic postulates are denied by other basic postulates, so that at certain points the system seems to be at war with itself’.3 All these kinds of social pollution described directly threaten the coherent delineation of a particular community, its defining edges and rules. They can be used to understand perceived threats to the architectural community itself after the end of the second world war, and to characterise those threats as a battle of the pure versus the hybrid.

1.3 Interior of hall at Hunstanton School, Norfolk, UK (1956): Alison and Peter Smithson.

The architectural historian and critic, Reyner Banham, is acknowledged as the official chronicler of Brutalism. He himself along with Alison and Peter Smithson was a member of the self-styled Independent Group, an avant-garde of artists and architects, formed in London in 1952. They originated both the idea and the term ‘Brutalism’. It is from the activities and concerns of the Independent Group that he identifies the genesis of the style in his 1966 book The New Brutalism.4 For Banham, it’s clear that what the profession understood as ‘architecture’ was under threat both from the Festival Style, and also from widespread local authority architecture of the immediate post-war years,

a style based on a sentimental regard for nineteenth century vernacular usages, with pitched roofs, brick or rendered walls, window boxes, balconies, pretty paintwork, a tendency to elaborate woodwork detailing and freely picturesque grouping.5

He goes on:

The younger generation, viewing these works, had the depressing sense that the drive was going out of Modern Architecture, its pure dogma being diluted by politicians and compromisers who had lost their intellectual nerve.6

The functionalist principles of modernist design were handed down from the European masters of the early years of the 20th century. These principles were, by the end of the 1930s, the established rules of architectural practice. Going back to Douglas, it was these rules – machine aesthetic and anti-decorative in appearance – which defined the internal lines, the borders, of architectural aesthetics as a system. And it is these rules, referred to by Banham as modern architecture’s ‘pure dogma’, which were perceived as polluted and transgressed by the post-war hybrid style.

It was not just the new style’s literal transgression of pure modernist lines with ‘elaborate woodwork detailing and freely picturesque grouping’ that threatened professional purity. It was the very fact of the hybridity of this new, debased, modernist style. Douglas’ statement that pollution threatens when there is ‘danger from internal contradiction … so that. . . the system seems to be at war with itself is particularly apposite here. Banham does not identify this as a problem of confrontation of on...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Walls Have Feelings: Architecture, Film and the City

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- How to Use This Book

- Part One: The Detail

- Part Two: The Interior

- Part Three: The City

- Endpiece

- Bibliography

- Acknowledgements

- Illustrations

- Filmography