- 328 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book explores how media and religion combine to play a role in promoting peace and inciting violence. It analyses a wide range of media - from posters, cartoons and stained glass to websites, radio and film - and draws on diverse examples from around the world, including Iran, Rwanda and South Africa.

- Part One considers how various media forms can contribute to the creation of violent environments: by memorialising past hurts; by instilling fear of the 'other'; by encouraging audiences to fight, to die or to kill neighbours for an apparently greater good.

- Part Two explores how film can bear witness to past acts of violence, how film-makers can reveal the search for truth, justice and reconciliation, and how new media can become sites for non-violent responses to terrorism and government oppression. To what extent can popular media arts contribute to imagining and building peace, transforming weapons into art, swords into ploughshares?

Jolyon Mitchell skillfully combines personal narrative, practical insight and academic analysis.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Promoting Peace, Inciting Violence by Jolyon Mitchell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Inciting violence

Chapter 1

Visualising holy war

Prologue

At first glance they appear to be a regular set of stained-glass windows. Most of the images are framed by an ornate Gothic canopy, which gives them a three-dimensional quality. From a distance, they look similar to thousands of other windows to be found in churches and cathedrals all over Europe. On closer inspection, they reveal a surprising iconography.

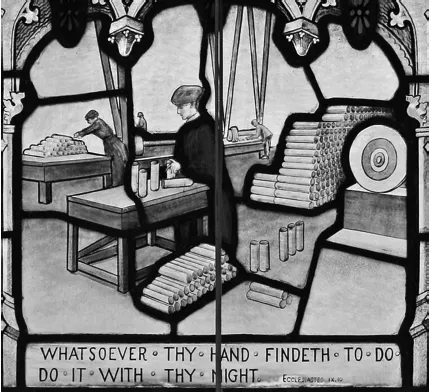

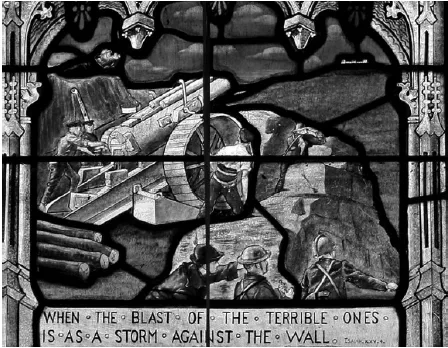

A woman in a bright blue dress holds a golden shell. This is not Mary taking something from the sea, but rather a factory worker packing explosives into metallic casings. Behind her are neatly arranged stacks of shells, reminiscent of stored scrolls (figure 1.1) preserving wisdom. Beneath a text from the Hebrew bible: ‘Whatsoever thy hand findeth to do, do it with thy might’ (Ecclesiastes 9.10, KJB). There is an intensity in her stare, redolent of a saint in prayer clutching a sacred object. The uses of her devotion are made more transparent in the pane above (figure 1.2). A solid silver-coloured object, a howitzer, dwarfs several soldiers. Sleeves rolled up, they prepare their weapon of war. The long brown shells by their feet look like a pile of logs, awaiting use on a winter fire. The heavy gun is directed towards a fort in the distance. Another text from the bible is placed below to underline how the ‘blast of the terrible ones is as a storm against the wall’ (Isaiah 25.4). The diversity of the soldiers’ hats and uniforms, reminiscent of a 1915 Robert Baden-Powell propaganda poster,1 suggests different nationalities working together to fight a common faceless enemy (figure 1.2).

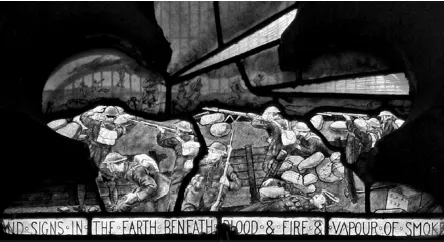

The smaller stained-glass image above captures a moment in the trenches where British soldiers, in khaki uniform, hunker down for cover. In contrast to the war artist Paul Nash's depiction of no-man's land as a deserted, tree-shattered and broken landscape (We are Making a New World, 1918), this window is full of soldiers and action. Out of the shadows German troops charge, spewing red liquid fire as they advance. Two of the defenders return shots with a Lewis machine gun, one more soldier turns his back on the fighting and covers his eyes, while another lies dead with blood oozing from his head. This is by far the most explicitly violent of all the images found in these three windows (figure 1.3).

Figure 1.1 The Shell Factory. 1919 stained-glass window from St Mary's, Swaffham Prior, Cambridgeshire. Photograph courtesy of Steve Day. About 1 million women worked in munitions in Britain during the First World War. They were often called ‘Tommy's Sisters’ or ‘munitionettes’.

Below the scene are the following words: ‘And signs in the earth beneath blood & fire & vapour of smoke’. This text is taken from a New Testament scene describing the day of Pentecost where listeners are surprised to find they can hear their own native languages being spoken by foreigners. Different nationalities are brought together (Acts 2.1–21). In these early twentieth-century windows these prophetic words are taken out of this narrative context and juxtaposed with a graphic depiction of nations violently divided. This snapshot of trench warfare is more evocative of the breakdown of communication between nationalities following the building of the tower at Babel (Genesis 11.1–9) than of the moment at Pentecost when communicative divides are overturned and nationalities are brought back together. More precisely, in the book of Acts, Peter is quoting the prophet Joel and is seeking to persuade a gathered crowd that disciples speaking in many different languages is a sign not of drunkenness but of an outpouring of the spirit where blood, fire and smoke are signs of the ‘last days’. At this apocalyptic moment ‘young men will see visions’ and ‘old men will

Figure 1.2 A Howitzer. 1919 stained-glass window from St Mary's, Swaffham Prior, Cambridgeshire. Photograph courtesy of Steve Day.

Figure 1.3 Liquid Fire. British and German soldiers engage in trench warfare. 1919 stained-glass window from St Mary's, Swaffham Prior, Cambridgeshire. Photograph courtesy of Steve Day. Flamethrowers (Flammenwerfer) were first used in 1915 by the German army at Verdun and then Hooge.

dream dreams’ (Acts 2.17–21). Unlike the apocalyptic visions of Otto Dix (Der Krieg: War Triptych, 1929/1932), the visions expressed through these windows provide only glimpses of the suffering caused by trench warfare. The same set of stained-glass panes also includes other tools of war that brought blood and fire, such as an armoured tank, and a biplane marked with a German cross. While not romanticised, the nightmare visions emerging out of the reality of ‘the war to end all wars’ is largely softened in these pictures, which have a cartoon-like quality.

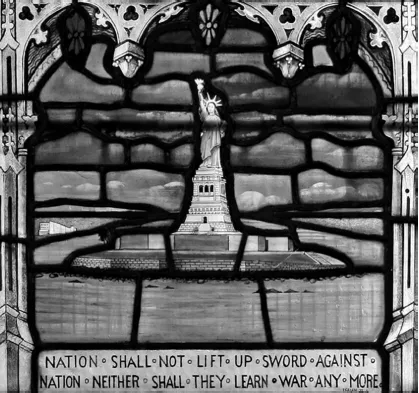

This style is also to be found in two other nearby windows. Whereas the first window depicts some of the newest military technology, the second portrays some ways in which the effects of these brutal tools of killing were mitigated. In simple colours there is a motor field kitchen and a YMCA hut as places of refreshment, a steel net to keep enemy submarines at bay, a ‘French drawing-room converted into a hospital with English Red Cross nurses attending to the wounded’, a military chaplain ‘blessing a dying man on the field’ and the Statue of Liberty, Liberty Island, New York (figure 1.4).2

Figure 1.4 The Statue of Liberty in New York Harbour. 1919 stained-glass window from St Mary's, Swaffham Prior, Cambridgeshire. Photograph courtesy of Steve Day. It depicts Frederick Bartholdi's neoclassical sculpture, a gift from the French people to the USA, which was dedicated in 1886.

Beneath the statue is a prophetic text taken from the book of Isaiah: ‘Nation shall not lift up sword against nation neither shall they learn war any more’ (Isaiah 2.4). While the preceding sentence from Isaiah, which speaks of ‘swords being beaten into ploughshares’, has been omitted, taken together the windows are clearly intended to point forwards to time when there will be no need for war. Alongside these two war windows is a contrasting third, where images of war are entirely absent. Instead, sheep feed, oxen plough and crops are harvested. Green glass is introduced, evoking more a sense of a ‘green and pleasant land’ than a country ‘fit for heroes’.3 These images are reminiscent of the frescoes in the Sala della Pace in Siena's Palazzo Pubblico, which show the effects of good government: the frescoes portray an agricultural idyll, where the benefits of hard work and peace are visually brought to life.4

What do these twenty-seven images, encompassed within these three windows in a small parish church in Cambridgeshire, reveal about the violence and peace they depict? On first viewing, these images could easily be interpreted as incitements to join the First World War effort, whether by embracing the tools of war, by resisting the ‘diabolical’ weapons of the enemy or by caring for the injured. The aim is to lead the viewer through the nightmare vision of the trenches to a new world worth fighting for: a land of fruitful peace. An interpretation that views these windows as direct incitements to violence would be mistaken. They were created not during the war but nearly a year after its end, in 1919. Beneath the window and inscribed on a plaque are the following words:

War was declared on the 4th August 1914 these windows were inserted to commemorate the Great War and the men of Swaffham Prior who were killed in action or died of wounds or disease fighting nobly for God, King and country against the aggression and barbarities of German militarism.

These windows were therefore not wartime visual propaganda, to be catalogued alongside the Lord Kitchener ‘Your Country Needs You’ poster,5 but rather an idiosyncratic war memorial. Here was a visual form of commemoration both of the war itself and to the twenty-three men who died because of the war and who were connected with the small agricultural village of Swaffham Prior in Cambridgeshire.6 References to the ‘aggression and barbarities of German militarism’ illustrate how the tone of this plaque is far from conciliatory. This is reinforced not only through the accompanying texts but also through the unusual images.

Introduction

This small local memorial was created in a few months during 1919. Like so many others, it was born of out of the trauma of nearly 1,600 days of conflict. They are part of the graphic ‘vocabulary of mourning’ which emerged during and after the First World War.7 This memorial, incorporating the windows, a plaque and a cross at St Mary's in Swaffham Prior is but one example of over 40,000 memorials in the UK and many thousands more local and national memorials scattered across Europe.8 The UK's National Inventory of War Memorials lists over 2,000 stained-glass window memorials.9 Many of the memorials found in Britain are now overlooked in what the poet Geoffrey Hill describes as ‘a nation with so many memorials’ yet ‘no memory’.10 Nevertheless, these war and peace windows from an ancient parish church in Cambridgeshire, England, raise questions pertinent to understanding not only other war memorials but also the role of media and religion in promoting peace and inciting violence.

I therefore analyse these pictures, in this chapter, in order to reflect upon the relation between remembering and inciting violence in a religious context. There is already considerable research both on the uses of propaganda during the First World War and the significance of memorials in the shadow of the war.11 Far less common is an approach that considers the relation of memorials to propaganda. What can be learnt from these memorials about the after-life of wartime propaganda? In other words, how far did incitements to violence produced during the war live on after the end of the war? What evidence does this set of twenty-seven memorial images provide for understanding how violence can be incited? Over the last two decades there has been a turn from examining state-produced propaganda to private sector propaganda, such as art, poems, plays and sermons. This reflects an earlier move by researchers to analyse not only state-funded memorials, but also privately commissioned sites.12

These developments in the way propaganda and memorials are analysed provide the backdrop for my own discussion. In this chapter I focus primarily upon this privately funded local memorial that is preserved in a small parish church. In order to answer questions about inciting violence, I begin by briefly considering the mixed responses that these windows have provoked. I then go on to consider five connected processes inextricably connected with these windows: grieving, commemorating, justifying, remembering and vilifying. My aim in this chapter is not to interrogate recent revisionist accounts of the First World War that challenge ‘the myth’ that the war was a ‘disaster’;13 my intention is rather to use this case, which emerged out of the war, to investigate some of the ways in which conflict can be depicted and visualised as something sacred, even after the war is over and most of the dead are buried.

‘A Strange Memorial’

Under the headline of ‘A Strange Memorial’, the London-based daily newspaper the Morning Post described how the ‘inhabitants’ of Swaffham Prior ‘elected to place in the parish church painted windows representing various war activities, with explanatory texts beneath’. In this article they are described as a ‘curious war memorial’ (25 February 1920). An unnamed correspondent, for the Manchester-founded tabloid the Daily Sketch, was even more outspoken: ‘Many sins against good taste have been committed in the name of war memorials, but few, perhaps are more flagrant than that which has occurred at Swaffham Prior, a village near Cambridge, famed for its two churches in one churchyard’. After describing how the village ‘has taken the phrase “war memorial” literally’ by producing ‘realistic memorials of the war’ with depictions of a Zeppelin, a tank or an aeroplane, the article concludes with the (incorrect) claim that ‘there is one hope. ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of figures

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- PART I Inciting violence

- PART II Inciting violence

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Filmography

- Webography

- Index