- 228 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Body Language for Competent Teachers

About this book

Non-verbal skills are invaluable for teachers in getting their own messages across to classes and understanding the messages pupils are sending them.

Here an educational psychologist and a classroom teacher join forces to show new teachers in particular how to use gesture, posture, facial expression and tone of voice effectively to establish a good relationship with the classes that they teach. Each chapter is illustrated with clear drawings of pupils and teachers in common classroom situations and accompanied by training exercises aimed at improving the new teacher's ability to observe both her class and her own practice.

A section at the end of the book gives suggested solutions to some of the exercises and the final chapter, addressed to staff responsible for their colleagues' professional development, provides suggestions for half and whole day courses.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Education GeneralChapter 1 Introduction

UP THE SWANEE?

The phrase The Blackboard Jungle’ epitomises the frustrations, anxieties and cynicism of those involved in the stressful occupation of teaching. It aptly highlights the endless tangle of theoretical advice and pedagogical practice, populated with such strange creatures as reports, examinations, preparation, capitation, attainment targets, folklore and headteachers. Little wonder, then, that many student and probationary teachers enter the jungle well-schooled in identifying the fauna and flora, but wondering why their training has not armed them with a practical ‘machete’ with which to cut a preliminary path.

One particularly painful and thorny tangle for many new teachers is classroom control. Deviant and disruptive behaviour can divert them away from their carefully planned teaching programme, maybe never to return. It is easy for any experienced teacher to recall their early days in the classroom when survival ranked high on the list of priorities, and when endless evenings were spent worrying neurotically about certain classes and pupils.

Solutions were hard to come by; every promising path ended abruptly in a seething morass, and the class showed a mulish tendency to bolt in every direction but the right one. As a new teacher, you are in a position of having to break in a creature which you cannot directly force to do your bidding and which can collectively outrun you, both literally and metaphorically. We therefore make no apology for concentrating, at the outset, on how you can detect, from the laid-back ears or rolling eye, the signs of trouble which need your immediate attention, as well as where a more soothing approach is required. Secondly, we look at the ‘hands’; the skills which allow you to establish and maintain effective control and authority—unless you meet a bucking bronco of a class. A very small number of children and classes are uncontrollable, even by the sanctions available to an experienced teacher.

However, you need to go further, not only to catch and tether, but to persuade the mule to follow, to set up an environment in which authority and control become merely subsidiary. Though we have left the positive side of the classroom relationship to last, this is not a reflection of its relative unimportance—any more than our omission of anything related to the curriculum means it does not matter what teachers teach. Children have instrumental views of their teachers (e.g. Docking 1980, Nash 1974) they expect them to teach rather than to be friendly, and this expectation is likely to be increased with the National Curriculum.

Some may regret this lack of true friendship between teacher and class, but this phenomenon is not confined to the school. Among adults, friends are usually similar in age and status and friendships do not normally develop between work colleagues who occupy markedly different positions in the hierarchy. You cannot be truly a friend to the children, simply because you are an adult, and therefore you cannot establish a relationship based on true reciprocity. Inevitably you define the relationship, if only because if you fail to fulfil the children’s expectations, they may consider themselves released from the need to attend (Nash 1974). Nash found that if the teacher did not meet the children’s expectations that she should control and teach them, they rebelled against her; these were norms from which she was not readily allowed to depart. ‘Friendliness is something of a bonus’ as Nash says, and he feels that novice teachers need to learn the rules the class expects.

Perhaps the biggest hurdle to clear in arriving at an appropriate relationship lies in the very nature of most teachers. As a breed we tend to be sympathetic to the potential dangers and problems which can affect our charges, and we are usually intent upon establishing, as quickly as possible, an empathy from which we can cater for their individual needs. It is not surprising, therefore, that for so many years, teacher training courses should have concentrated on pupil-based methods. Courses in the sociology, psychology and philosophy of education have tended, most laudably, to place emphasis on the factors affecting pupil performance. Government departments and other bodies have made part of the basic student teacher vocabulary such expressions as ‘equality of opportunity’, ‘special needs’, ‘moral danger’ and ‘core curricula’. No one is denying the immense importance of these factors or disputing their place within the training process, but you will not find yourself in a position where you have the power to influence school practice in response to these pastoral and curriculum needs for some period into your career. You are unlikely to get such influence until you have demonstrated effective classroom skills.

ALL THE CLASS A STAGE

Whole-class teaching is very different to most situations in the normal social environment for which everybody has extensively practised social skills. You need to accentuate some of your existing skills to deal with this situation, and to abandon others. In normal conversation, for example, most of us are skilled at detecting, from the relevant nonverbal signs, if we are boring our friends, and can shift the topic of conversation until we detect more interest; but you cannot allow the children the same freedom to dictate the curriculum.

In the last resort, teachers have no sanction which can cow a child into submission (given that he has not been suspended from the school!) and in an average-sized class you cannot physically stop a number of children who are determined to be disruptive. Ultimately you cannot force children to learn; you must persuade them that to attend to what you propose to teach them is preferable to any alternative activity. Your chances of doing so are much greater if you can present your material in an interesting way and when the class cooperate with you, reward them in a way which they appreciate.

Many readers may wonder why it is necessary to look at non-verbal behaviour in such detail. Does it really matter whether you stand with your hands on your hips, or lean back against your desk? As we hope to show, it does. Readers may also wonder whether these aspects of performance are what teaching is all about. We would not wish to claim that they are, but research suggests that student teachers who were able to see their lessons as a performance which might be more or less successful managed better than those who were more completely and personally involved. Those who maintained a degree of detachment were more able to perform successfully. Selfknowledge, including awareness of one’s non-verbal skills, leads to effective performance.

The success or failure of any lesson will hinge on the effective use of the communication skills at your disposal. These should form part of your authority, felt subjectively by your class as linking you to the structure of your school. It may seem odd that such skills are observed by pupils and are understood in the sense that they convey authority. Political speeches offer a parallel—some politicians are more effective speakers than others; a few are really charismatic. The ability to speak persuasively can make a major contribution to political success, but Atkinson (1984) has shown that it depends on remarkably simple techniques. Effective speakers tend to package their ideas in formats, such as contrasts and three-part lists (‘Never in the field of human conflict has so much been owed by so many to so few’) which make it easy for an audience to predict when the speaker will finish making a point; they can then respond immediately. Speaker and audience then seem to be ‘on the same wavelength’ as each other. The natural assumption must then be that the speaker is particularly persuasive. In other words, the manner of delivery governs the response; because it is readily taken in, the audience will form their impression from the delivery, even if they remember little of the content.

Significantly, many of the signals used by politicians to coordinate an audience’s response are conveyed not in the words spoken, but through the non-verbal ‘back-up’ given in the speaker’s postural and facial cues, tone of voice and speech timing. Atkinson suggests that politicians have to use relatively simple techniques as this is the only way that the response of a large audience can be synchronised. Even so, speeches frequently misfire through faulty technique—if the audience cannot predict when to applaud, they either do not applaud at all, or only hesitantly, after an embarrassing silence. The speaker does not seem to be ‘getting through’. Charismatic speakers often seem to be able to time their speech so that it overlaps with the audience’s applause, but without the important points being drowned out; thus they appear to have to struggle to keep their audience’s enthusiasm under control. Atkinson suggests that most interactions, involving smaller numbers, will be more complex, and this certainly seems to apply to teaching.

Formal or informal? And what about the subject?

The more informal the approach and the greater the part of the children in the smooth running of the lesson, the more subtle your classroom skills need to be to maintain their interest in tasks which some at least would not have chosen freely. In a generally formal school setting, as an inexperienced teacher you can derive considerable support from the structure of the school rules, provided that you make sure you know them thoroughly, and can conduct lessons which are effective even if your relationship with the class is rather cool and distant. In such a setting the pupils are equally aware of how, as teacher, you should show your authority; any shortfall on your behalf may be immediately perceived as a sign of weakness. ‘Master teachers’ in such schools, who are often highly popular with their classes, have much warmer and more humorous relationships with their pupils. You can aspire to this desirable situation only as your skills improve; as we shall show, such relationships depend on the class’s knowledge of the limits you will allow. Experienced teachers who move to a new school are sometimes surprised by the sudden need to put effort into controlling their classes; they are not always aware how much they previously relied on their thorough, but subliminal, knowledge of the formal and informal procedures of their old school, and their reputation among the children.

More progressive and informal school settings make the inexperienced teacher’s task easier in some ways, because there is less of a ‘them and us’ atmosphere to set the children against you. You still need authority to convince them that your subject is worth attending to, and to get them to work steadily through the difficult or dull areas which are present in every subject. Where children expect warm and non-restrictive relationships with teachers, you must exercise your authority on a narrow borderline between coldness and over-familiarity. Every school contains difficult children; in dealing with these in the more informal situation you may have to rely more on your own authority, whereas in the more traditional establishment a framework of rules would provide more assistance. In fact our videotapes show that the real differences between classroom processes in progressive and traditional schools are less great than the apparent ones, simply because the children at schools tend to have more similar attitudes than their teachers. In a progressive school children may have no uniform, address the teachers by their first names and come in freely to choose their own seats in the classroom, but this does not mean they will treat you as a friend; in a formal school, uniform, lining up outside the classroom before going to designated seats, and addressing you as ‘Sir’ or ‘Miss’ are no guarantee of order—yet nor do they prevent warm relationships.

Figure 1.1 Six pupils occupying their positions during Ms. Discord’s lesson. The seating arrangement was of their choosing and held its own significance

Just as the similarities between different schools arise because their children react to teachers in similar ways, so similar tactics apply across subject boundaries in the secondary school. When children move from History to Home Economics, they are still the same children, and the different subject matter does not mean a complete difference in the social relationship they have with their teachers. Children are generally unaware of the intellectual structure of the particular subject, as you understand it—this would require knowledge which they are still in the process of learning. You cannot rely on the appeal of your subject itself, or the lure of completing their understanding of a particular branch of knowledge, to appeal to any substantial number of your pupils. Some children, especially in the younger age-groups, will be keen to learn, whatever you do. The majority will learn if you make it emotionally rewarding—especially if the alternatives are unrewarding. Their learning depends on a satisfactory teacher/pupil relationship, which is likely to remain independent of and unconnected to specific subject structures.

Teachers usually see themselves as teachers of a particular subject, and often feel that it is only possible to learn useful lessons from other teachers of their own subject. Pupils are far more likely to be impressed by what is happening in your relationship with them than by the finer points of the subject. What is more, their like or dislike of you may powerfully affect their attitude to the subject, and indeed whether they continue or drop it when option choices become available.

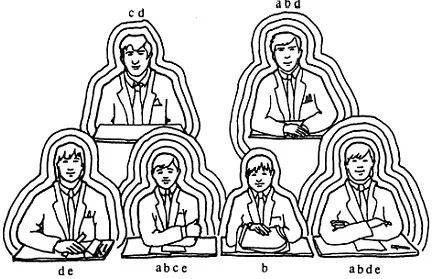

Figure 1.2 Shows the ‘ mitigators’ affecting the pupils, each generally regarded as having potential for slowing or damaging pupils’ educational progress:

a known family background conflicts

b reading age below 9:00

c probation, and or problems with the police

d anti-school/authority problems

e confirmed educational handicap other than low reading age (dyslexia etc.)

Hidden problems in the class

It is very likely that some of your pupils’ performance will be affected by psychological or social factors which interfere with their learning. Recognising these factors, formal or informal, in or out of the classroom, is a skilled process, normally resulting from the gradual accumulation of evidence about the child concerned. As a new teacher you may be able to make some early identifications, but usually you will simply not have sufficient information at the start to make effective judgements or to devise independently an appropriate strategy to solve such problems. The words ‘at the start’ are crucial; if you wait until you have got to know the children so that you can react to them as individuals, the class will long since have made up its mind about you and will be acting accordingly. You have to get to know twenty-five or thirty children; they only have to get to know one teacher.

As we shall describe later, an experienced teacher often makes it quietly clear that she is in charge within half a minute of entering the room. Videotapes of a class as they encounter a new teacher sometimes show their dawning realisation that she is a ‘soft touch’ after only five or ten minutes. Let us take an actual example. Ms Discord, a probationer teacher of music in a large comprehensive school, found herself taking a particularly difficult class of third-year pupils. It was evident from her initial contacts with them that although immensely enthusiastic, well prepared and sympathetic, she was unable to make these factors count in terms of her relationship with the form. After only a few lessons, the ‘honeymoon’ period, she had serious discipline problems and the pupils lost interest in the subject as their challenges to her authority increased. It is not hard to imagine the frustration and anxiety which this situation produced after all, her intentions were admirable. She had been told that the class were failing educationally, and that they had been labelled as failures. Armed with this limited information she had structured her lessons to cater for what she considered to be their probable individual needs. So what went wrong?

Firstly what she could not have known at the outset was the number and complexity of the problems affecting each pupil. Looking at these factors for just six members of that class, Figure 1.1 shows six boys as they ...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- GENERAL NOTE

- PREFACE—WHO THIS BOOK IS FOR

- CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION

- CHAPTER 2: WHAT IS NON - VERBAL COMMUNICATION?

- CHAPTER 3: STAGE DIRECTIONS AND PROPS

- CHAPTER 4: PUPIL BEHAVIOUR AND DEVIANCY

- CHAPTER 5: THE MEANING OF PUPILS’ NON-VERBAL SIGNALS

- CHAPTER 6: GETTING ATTENTION

- CHAPTER 7: CONVEYING ENTHUSIASM

- CHAPTER 8: CONFRONTATIONS; OR, THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK

- CHAPTER 9: RELATIONSHIPS WITH INDIVIDUAL CHILDREN

- CHAPTER 10: IMPLICATIONS FOR TRAINERS

- REFERENCES

- FURTHER READING

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Body Language for Competent Teachers by Chris Caswell,Sean Neill in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.