1

The Increasing Incidence of Disasters

It may seem hard enough to accept the idea that we have designed our way into many of the disasters that we have experienced of late, but harder still to accept that such disasters will likely occur with ever-greater frequency in the near future. The United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (ISDR) has data on global disasters, going back through records to 1900, with updated statistics through 2005.1

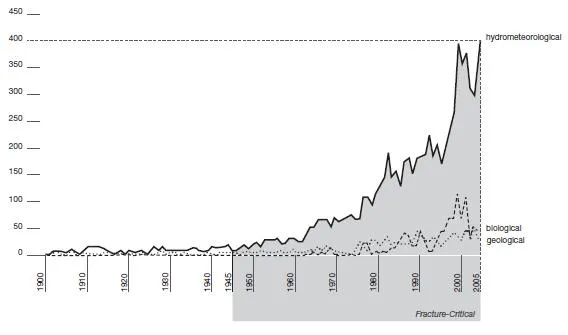

The increase in catastrophes, especially since World War II, is striking. After 1945, the incidence of disasters worldwide begins to move rapidly upward, with “hydrometeorological” events, such as droughts, floods, and storms, rising most noticeably: the number of weather-related catastrophes increased 400 times, by 2005, over the number of such disasters in 1900.2 While such events remain “natural” occurrences in the minds of many, the overwhelming evidence of the scientific community points to human activity such as the burning of fossil fuel in buildings, industry, and vehicles as having prompted climate change and the more extreme weatherrelated disasters that accompany it. As climatologist Mark Seeley has put it: “The more energy we put into the atmosphere, the more energy it gives back to us.”3 In other words, the more we can reduce the emission of climate-changing greenhouse gases, the more we can begin to lessen the number and intensity of hydrometeorological disasters.

Figure 1.1 Number of natural disasters registered in EM-DAT (an Emergency Events Database maintained by CRED) across the years 1900–2005. While data gathering and record keeping related to weatherrelated disasters have improved, that alone cannot account for the rapid rise in the number of such events occurring around the world as our climate changes.

Biological disasters, such as epidemics and insect infestations, and geological disasters, such as earthquakes, tsunamis, and volcanic eruptions, have also increased about the same amount during the twentieth century, roughly to thirty to forty-five times the number in1900. However, these two kinds of catastrophes have had different trajectories. Around the turn of the twenty-first century, the number of biological disasters spiked to over 100 times that of a century before, while geological disasters have never increased to more than fifty times the number in 1900.4 Both of these types of disasters, however, have similar causes: populations living in closer proximity, in over-crowded, unsanitary conditions that can generate epidemic disease and on unstable ground in unstable buildings that remain vulnerable to the hazards of tremors and tsunamis. Here, too, we have designed—or rather badly designed—our way into such disasters. At the same time, we can greatly reduce the loss of life and cost of damage of biological and geological catastrophes by ensuring that all people live and work in safe and sanitary conditions.

These hazards do not occur uniformly around the globe. Obviously climates differ from one location to another, as do factors such as density of population and vulnerability to geological or climatological events. Some events, such as the post-Katrina flooding along the Gulf Coast in 2005 or the Kobe earthquake in Japan in1995, outpace all the others in terms of cost, but remain relatively small percentages of the gross domestic products of the countries in which they occurred. Other events, such as the floods in Bangladesh in 2004 and those in North Korea in 1995, cost relatively little in absolute dollar amounts, but constituted a huge percentage of those nations’ economies.5 But, in the United States, those who think that disasters befall others need to think again.

The United States ranked third among countries most often hit by natural disasters and it leads the world in the cost of these events, with Katrina remaining the most expensive disaster to date, at an estimated $110 to $125 billion. And the United States alone absorbed over $365 billion dollars in disaster-related damages between 1991 and 2005, with only Japan and China coming close to that figure, and with the average cost of disasters in all other countries less than one-tenth as expensive.6 And yet, while the United States exceeds others in the cost of disasters generally, disasters have different geographies. While epidemic disease has increased eightyfold over the twentieth century, for example, the distribution of such diseases remains highly uneven. The number of people killed by biological illness, for instance, was one-third more in the least developed countries than in developing nations and 160 times more than in the most developed parts of the world.7

Some could argue that the criteria used by the Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED) in reporting these findings have skewed the data. For example, CRED uses a rather narrow definition of what constitutes a disaster: a “situation or event, which overwhelms local capacity, necessitating a request to national or international level for external assistance; [and] an unforeseen and often sudden event that causes great damage, destruction and human suffering.”8 Such disasters get recorded if they meet at least one of the following criteria:

-

ten or more people reported killed

-

100 people reported affected

-

declaration of a state of emergency

-

call for international assistance.

Considering the impact of disasters like the Katrina flooding or the Haitian earthquake, these criteria seem mild in comparison. But CRED has used these criteria consistently and so while someone might dispute the total number of disasters, the relationship between catastrophic events across the 105 years represented by the data remains the same. And as we will see, that relationship matters much more than absolute numbers.

At the same time, some might argue that changes in data gathering and reporting disasters have skewed the relationship among these events. Clearly, we have better data in recent decades because of the more reliable and consistent data gathering that digital tools and global communications allow. But, disasters rarely go entirely unnoticed, if only at a local level, and so we should trust the research that CRED and other organizations have done to ascertain, as accurately as possible, the incidence of catastrophes across the last century. To do otherwise would simply cloud the reality that we face as a human species: that the number of particularly weather-related disasters and the number of people on the planet since World War II have both grown exponentially.

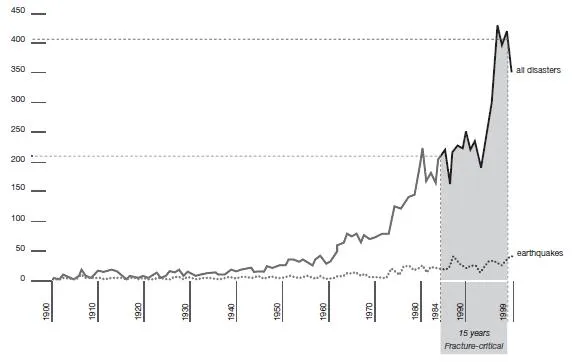

That rate of growth is key, as we will see. Exponential growth has the paradoxical effect of lulling us into complacency because of the peculiar nature of such growth. When something increases exponentially, even a benign or beneficial situation can become unmanageable and even devastating quite quickly. In 1996, for example, the number of weather-related disasters reported worldwide that year stood at roughly 175, a seemingly modest amount and less than the number reported in 1984. But by 1999 the number of such disasters had climbed to around 400, an increase of over 200 percent in just three years.9

Human population numbers have increased even more alarmingly. In 1950, world population stood at about 2.5 billion people; by 2005, it had increased to 6.5 billion, a 260 percent increase in a little more than half a century. By the end of 2010, the number stood at close to 7 billion.10 That it took our entire history to reach 2.5 billion and less than the average lifetime of one person to grow 260 percent shows the nature of the complacency that such exponential increases can instill. Those in the most developed parts of the world may not see the population growing that quickly and so may think that we have time to adjust to having so many more people on the planet than just a generation or two ago, but exponential growth actually gives us very little time to respond. We have become, literally, a species out of control, and the disasters we face remind us of that. Floods, earthquakes, and plagues have occurred on the planet and among species long before humans ever evolved. But those events, combined with our excessively large numbers, make such “natural” events catastrophic in their effects on us.

Figure 1.2 Trends in number of reported events. When comparing all disasters around the globe to the relatively stable incidence of earthquakes worldwide, we can see that the growing numbers of people living in hazard zones has greatly increased the number and severity of catastrophic events since the 1950s.

And not just on us. The CRED data primarily focuses on the direct effects of disasters on humans, with little or no mention of its impact on plant and animal life. And yet, the diminishment or destruction of other species and the ecosystems upon which they thrive can have long-term consequences for us. The oil spill off the Louisiana coast barely makes one of the ISDR criteria: with eleven people killed this was just one more than the ten-person number needed to declare it a disaster. But the impact on sea life and on the wetlands and along the shorelines of the Gulf Coast has been absolutely catastrophic, not only for the millions of plants and animals killed by the spill, but for the millions of people affected by the loss of those ecosystems for generations to come.11

2

Our Planetary Ponzi Scheme

These disasters to both human populations and to other species have not happened by accident; we have designed a system to maximize the rewards of a relatively few people, while threatening most others on the planet. This system has worked well for those at the top, but it has negatively affected enough other people or species to undermine its stability—even for those at the top. And over the last few decades, the devastating consequences of this have become too large to ignore, with billions of people living in abject poverty and an accelerating rate of species extinctions underway. To understand what we have put in place, we might turn to a metaphor, one that recent events have made readily apparent: we have, since at least the industrial revolution over the last two centuries, engaged in a vast Ponzi scheme with the planet.

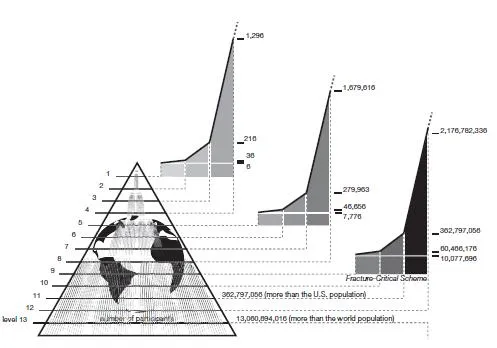

I first read of that idea on September 4, 2009 in an essay in The Chronicle Review , in which David Barash, a professor of psychology at the University of Washington, argued that “in our fundamental relationship to the natural world—which is, after all, the fundamental relationship for everyone—we are all Madoffs.”1 Barash referred to the over $50 billion Ponzi scheme that Bernard Madoff perpetrated on his investors, using the funds he received from new clients, lured by his claims of guaranteed high returns, to pay earlier investors the money that he had promised them. A Ponzi scheme holds enormous appeal to unscrupulous people. It can make its perpetrator, and its initial investors, fabulously wealthy. But as we have seen with Madoff’s fraud, such schemes cannot last; eventually they run out of resources to keep feeding those at the top. As Barash points out, such “pyramid schemes are not sustainable. Eventually they fail. It isn’t possible to keep recruiting a never-ending supply of suckers.”2

Madoff, though, did us all a favor by demonstrating something that we hadn’t recognized before. The original Charles Ponzi, who invented this form of fraud, had a scheme that lasted a matter of months in 1920 before it came crashing down. But Madoff did something Charles Ponzi could only dream of, realizing that if a Ponzi scheme becomes large enough and pervasive enough, it becomes—paradoxically—harder to see and more difficult to accept. In that sense, Madoff played upon an understandable aspect ofhuman nature. Once we become dependent upon something and have invested so heavily into it, we have every incentive to want to keep it going, even after we know it to be unsustainable. Some people had suspicions about Madoff and his promised returns on investments as too good to be true, but their warnings went unheeded because no one wanted to believe them.

Figure 2.1 A Ponzi scheme like that pursued by Bernard Madoff has a fracture-critical nature because it requires exponentially increasing numbers of participants to keep it going and because it inevitably collapses, suddenly and often without warning.

Madoff’s Ponzi scheme may go down in history as just another example of the financial fraud and unethical behavior that became all too common in an era in which capitalism has become “the worst enemy of humanity” as Bolivia’s president, Evo Morales, has called it.3 And to those of us who never invested with Madoff, his conniving may seem far from our concerns. But, as Barash suggests in his essay, when it comes to our treatment of the planet, “we are all Madoffs,” or at least all participants in a Madoff-like pyramid scheme in which the wealthiest populations in the world pay themselves handsome returns by drawing down the available resources of the planet and inexpensive labor of poor people around the world.4

This has gone on for so long and become so enormous that we do not recognize the Ponzi-like nature of the global, industrial economy. Nor do we want to. Those of us living in developed nations have far too much at stake to want to see our standard of living come crashing down, and so we do what Madoff’s investors must have done when warnings of a possible Ponzi scheme went public: we look the other way and don’t want to know about it, in hopes that it isn’t true. But it is true. The combination of modern technology and finance have enabled the last seven or eight generations of people to consume finite resources and exploit human labor at a rate never before seen in our past and no longer sustainable on into the future. We have, like all Ponzi schemes eventually do, run out of suckers, as Barash put it. It now takes 1.5 planets to meet the current needs of humans on our one globe, and with the base of our pyramid now larger than the world it stands on, the structures upon which we all now depend will become increasingly unstable and liable to sudden collapse.5

Barash asks this rhetorical question at the end of his essay: “Madoff eventually got 150 years in the slammer and worldwide derision. What’s in store for the rest of us?”6 What, indeed, lies in wait for the rest of us when the potential collapse we face doesn’t just involve money, but fundamental aspects of human existence, such as a climate cool enough to grow the food we need to eat or to replenish the fresh water we need to live? Many will want to dismiss this Ponzi scheme metaphor as just that: a metaphor, a creation of our imagination and so not worth taking seriously. To which I would respond with Pascal’s wager. Blaise Pascal, the seventeenth-century mathematician and theologian, argued that we cannot know if God exists or not, but that we would be wise to wager that he does, for if he doesn’t exist and we bet that he does, we have lost nothing, but if he does exist and we bet that he doesn’t, we have lost everything.7

The same argument applies to our Ponzi scheme with the planet. If Barash’s metaphor is wrong and we bet that it is right, we have lost nothing. If, for example, we reduce our use of fossil fuels, curb our use of fresh water, limit our generation of greenhouse gases, and generally try to live in more ecologically friendly and more socially just ways, we will continue to live fulfilling lives—and healthier lives in the process. But, if Barash’s metaphor is right and we bet he is wrong, we stand to lose everything. Like life without God to the religiously minded, we cannot maintain human civilization without adequate resources or sustain human life without enough food or fresh water. And if Barash’s metaphor is right, those in the wealthiest countries also have the most to worry about. As the collapse of Madoff’s Ponz...