![]()

Part 1

Theoretical foundations

![]()

Stated simply, the role of theory is to inform practice, although the reality is that the interface between the two is not always as straightforward as one might hope. In this book we argue that interventions to reduce offending should be based on knowledge about the causes of crime, be informed by an empirically supported theory (or theories) of behaviour change, and be consistent with what has been shown to be effective in changing offending behaviour. Theory is, therefore, imperative in terms of describing and understanding the processes involved, in gaining knowledge, and accumulating evidence (Lippke and Ziegelmann, 2008); evidence which is subsequently the basis for developing effective and interpretable interventions. Before we discuss current practice models of offender rehabilitation, there is a need to consider key theoretical explanations for why people commit crime and, equally importantly, why they stop committing crime.

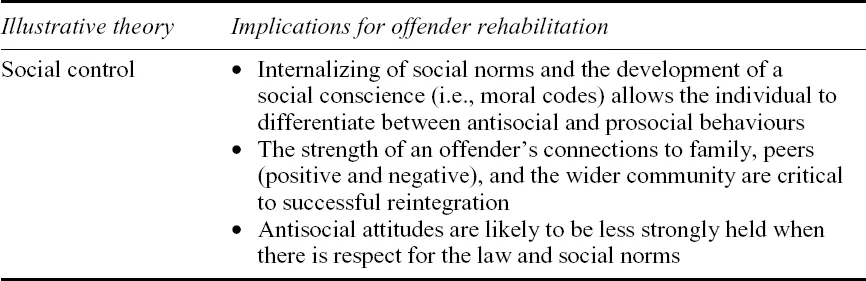

Theories of crime and criminal behaviour

There have been many theories postulated that seek to explain the causes and correlates of criminal behaviour. Several attempts have been made to themati-cally organize different theories according to whether they take a broad, large-scale and society-wide ‘macro’ view, or adopt a ‘micro’ approach that considers crime from the perspective of the individual. One particularly useful organizing scheme is that proposed by McGuire (2004), which consists of five discrete but interconnected levels of theory that range from the social to the individual; or from structural causes (i.e., offenders are victims of their circumstances in some way) to views of individual agency (i.e., people are responsible for their own life situation). Level 1 theories (e.g., social control theory) are macro accounts; Level 2 (e.g., differential opportunity theory) offers locality-based accounts; socialization and group infl uence processes are at Level 3 (e.g., differential association theory, social learning theory, developmental criminology); crime events and ‘routine activities’ are at Level 4 (e.g., routine activity theory, rational choice theory); and individual factors are at Level 5 (e.g., neutralization theory, psychological control theories, social cognitive theory). Table 1.1 provides a brief explanation of the main focus in research and theory construction for each unit of analysis, the broad objective theory in the particular area, and examples of various approaches at each level. This is followed by examples of theories from different levels which are particularly relevant to understanding the proximal and distal antecedents of an individual offender’s behaviour and which have also served to inform the development of offender rehabilitation programmes. It is beyond the scope of this book to provide an analysis of the relevant merits of each of these theories, but some key theories are described in the following sections followed by an analysis of how each theory might contribute to offender rehabilitation practice.

Table 1.1 Theories of crime: Structural to agency (based on McGuire, 2004)

Level I: Society

Social control theories

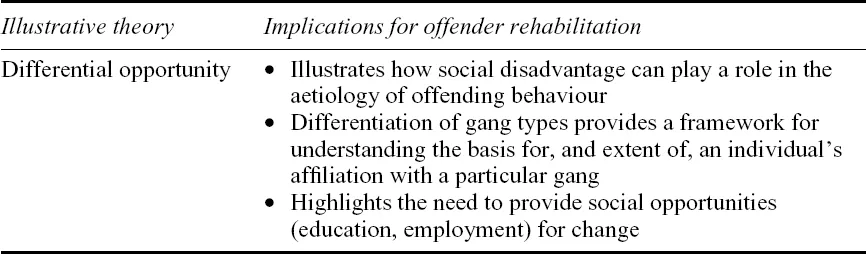

Social control theories operate on the premise that all human behaviour is, by nature, antisocial and that people must be controlled in order to prevent their involvement in crime. The most commonly cited social control theory is that of Hirschi (1969). According to Hirschi, criminal behaviour occurs in the absences of a controlling force which he postulates is the social bond; that is, the link between individuals and society. People refrain from engaging in criminal acts because they value this bond and do not want it damaged. When the individual’s bond to society is weakened or broken, there is an associated increase in the likelihood that they will engage in antisocial and/or criminal behaviours. This bond is said to have four elements: attachment, commitment, involvement and belief.

Attachment is the affective and emotional element of the bond and represents the value placed by the individual on his or her relationships with significant others (e.g., parents, school, peers) and is critical in terms of accepting social norms and developing a social conscience. According to Hirschi, individuals who are strongly attached to others and care about what they think will not want to disappoint them and, for this reason, will be less likely to engage in criminal behaviour.

Commitment (also referred to as ‘stakes in conformity’) is the rational element of the social bond. It refl ects the degree of time, energy and effort invested in conventional lines of action (i.e., the support of and equal participation in social activities that tie an individual to the moral and ethical code of society). People who build an investment in life, property and reputation are less likely to engage in criminal acts that will jeopardise their social position and, therefore, are less engaged in criminal behaviour.

Involvement refers to a preoccupation with activities that stress the conventional interests of society. Individuals with a heavy involvement in conventional activities do not have time to engage in delinquent or criminal acts. Thus an involvement in areas like school, family or sport serves to insulate the individual from the potential for antisocial behaviours that may result from idleness.

Finally, belief is the extent to which an individual recognizes and has respect for the legitimacy of societal norms and laws as well as those people and institutions which enforce these laws. Hirschi argued that people who live in common social settings share similar human values and if these beliefs are weakened or absent, the individual is more likely to engage in antisocial or criminal acts. As such, individuals who believe in the norms of society are more likely to act in accordance with those norms and be less likely to engage in criminal behaviour.

The assumptions underlying social control theory were illustrated in Payne and Gainey’s (2004) investigation of offenders’ experience of house arrest with electronic monitoring. Consistent with the proposition that connection to society is vital in terms of preventing crime, the 49 offenders surveyed in the study recognized that they had too much to lose should they breach the conditions of their electronic monitoring conditions. There was also a strong appreciation that this particular form of sanction provided an opportunity to maintain family and employment bonds while some offenders indicated that it was the controlling nature of the sanction that helped ‘keep them in line’ (p. 432). The authors concluded that this form of sanction demonstrated a new sense of trust being placed in the offenders by society which, in turn, should serve to strengthen their social bonds (see Gainey et al., 2000). It is this stronger bond to society, family and work that is thought to reduce the likelihood of future misconduct on the part of the offender by effectively teaching them self-control.

Table 1.2 Implications of Level I theories for offender rehabilitation

Level II: Community

Differential opportunity theory

This theory, proposed by Cloward and Ohlin (1960), combines notions of strain (Merton, 1957), differential association (Sunderland, 1939; see below) and social disorganization (Shaw and McKay, 1969) to explain the development of delinquent subcultures. The central premise of the theory is that despite an ideology of equal opportunity, people from different levels of the social hierarchy will have different chances of reaching common success goals. Strain experienced in the pursuit of these goals can lead to adjustment problems which can, in turn, result not only in the use of illegitimate means to gain success goals (crime) but also in the feelings of oppression that underpin sub-cultures. In other words, adolescents who form delinquent subcultures have limited opportunities to legitimately access conventional goals (goals which they have internalized) and their inability to downwardly revise their aspirations leads to intensive levels of frustration and exploration of non-conformist alternatives in order to reach these goals. Some of the barriers to success identified in this theory include educational, cultural and economic obstacles. And while deprivation and strain can and do play a role, whether the individual has a positive or negative response will depend to a large extent on the available opportunities and role models, both legitimate and illegitimate.

The authors also reasoned that delinquent subcultures fl ourish in lower socio-economic areas in different forms so that the means for illegitimate success are no more equally distributed than those for legitimate success. Moreover, the form of delinquent subcultures which emerges from within a society will depend, to a large extent, on the degree of integration present in a community. Cloward and Ohlin (1960), proposed this could result in one of three different types of gangs. The first, the criminal gang, develops in areas where conventional as well as non-conventional values are integrated by the close connection of illegitimate and legitimate businesses. Given the primary goal of gang activity is to make money, the lack of legitimate means is replaced by illegitimate ones, such as theft or extortion. Typically stable in nature, older criminals serve as role models for younger gang members, teaching them the criminal skills necessary to successfully maintain their illegitimate pursuit of conventional goals. The second type, the confl ict or violent gang, has few legitimate or illegitimate opportunities. Found primarily in poor, socially disorganized neighbourhoods, this type of gang is unstable and non-integrated with the primary goal being the development of a reputation for toughness and destructive violence. Finally, the retreatist gang is equally unsuccessful in legitimate and illegitimate means. Unable to fight well or profit from their crimes, these gangs are known as double failures with gang members retreating into a world of drugs and alcohol.

Table 1.3 Implications of Level II theories for offender rehabilitation

Level III: Social groups

Differential association theory

Differential association theory is a social learning theory of crime developed by Sutherland (1947). Social learning is a general theory that offers an explanation for the acquisition, maintenance and change in criminal and deviant behaviour that incorporates social, non-social and cultural factors that operate both to motivate and control criminal behaviour and promote and undermine conformity. According to Sutherland, criminal behaviour is learned in much the same way as any other behaviour. This involves learning (a) the techniques of committing crimes and (b) the motives, drive, rationalizations and attitudes favourable to violations of the law. Consistent with learning any social patterns – conventional or deviant learning takes place in groups, particularly intimate social groups such as family or peers. Accordingly, the tendency of any individual towards conformity or deviance will depend on the relative frequency of their association with others who encourage either conventional behaviour or, alternatively, norm violation. The theory incorporates nine principles to explain the process by which an individual becomes a criminal:

1. | Criminal behaviour is not innate, it is learned; |

2. | Criminal behaviour is learned through a process of communication, which is active and open-ended; |

3. | The principal part of the learning takes place in intimate groups; it is in these primary groups that the individual is said to define who they are; |

4. | The learning of criminal behaviour involves not just the learning of techniques that enable the individual to commit crime, but also the learning of motives and attitudes; |

5. | People learn motives and attitudes about the law that can be either positive or negative (this process also takes place within primary and intimate social groups); |

6. | People differentially associate with the attitudes and motives that are favourable to violating the law (i.e., having been provided with excessive definitions that are favourable to violating the law, the individual will elect to behave in a criminal way); |

7. | Differential associations depend on specific variables: frequency (how often the learning takes place), duration (how long the learning episodes are), priority (the age at which the criminal learning began, with earlier onset being associated with greater impact), and intensity (the importance or prestige of the learning source); |

8. | Learning criminal behaviour involves the same mechanisms as any other type of learning; and |

9. | Criminal behaviour is not always an expression of needs and values (e.g., not all homeless people steal in order to eat). |

The basic prediction of this theory is that people offend because they have been socialized in families and/or groups with pro-criminal norms. Empirical evidence certainly supports this proposition. For example, differential association theory has been used to explain juvenile delinquency and gang culture (Haynie and Osgood, 2005) although it is sometimes difficult to determine whether the delinquent behaviour preceded the delinquent friends. Despite this limitation, Gendreau et al. (2006) highlight that differential association can be used to explain how pro-criminal attitudes can be transformed into pro-social patterns of behaviour by reducing contact with antisocial groups. Differential association has also been used to explain white-collar crime. This research suggests white-collar crime is the result of learned definitions (i.e., individual orientations and attitudes toward a given behaviour) and experiences that occur within the workplace (Piquero et al., 2005). Criminal behaviour is most likely to occur when there is a convergence between learning the drives, motivations and rationales to commit white-collar crime and when the definitions toward committing white-collar crime outweigh the definitions against law violations (see Akers, 2004 for a review).

Differential association-reinforcement theory

This theory was an attempt by Burgess and Akers (1966) to combine the approach of differential association with the principles of operant conditioning from behavioural psychology. Consistent with Sutherland (1947), they argued that people are first indoctrinated into deviant behaviour via differential association with deviant peers. Through the process of differential reinforcement – the balance of anticipated or actual rewards and punishments that follow or are the consequences of behaviour – the individual then learns to refrain from or commit crime at any given time. It is the balance of past, present and anticipated future rewards and punishments that is said to be responsible for whether the individual commits a crime (and continues to do so or desists in the future). The greater the value, frequency and probability of reward for deviant behaviour (when balanced against the punishing consequences and rewards/punishment for alternative behaviour), the greater the likelihood it will occur and be repeated (Akers and Jensen, 2006). While reinforcers and punishers can be non-social (e.g., the direct physical effects of drugs and alcohol), Akers and Burgess propose that the majority of learning in criminal and deviant behaviour is the result of direct and indirect social interaction whereby others (a) directly reinforce behaviour (via words, responses, presence and behaviour), (b) provide the setting for reinforcement (discriminative stimuli) or (c) are the conduit through which other social rewards and punishers are delivered or made available. The nine principles devised by Sutherland were reformulated into seven principles which are used to explain how the individual arrives at the point where criminal behaviour is activated by discriminative cues (norms):

1. | Criminal behaviour is learned according to the principles of operant conditioning; |

2. | Criminal behaviour is learned both in non-social situations that are reinforcing or discriminative and through that social interaction in which the behaviour of other persons is reinforcing or discriminative for criminal behaviour; |

3. | The principal components of learning occur in groups; |

4. | Learning depends on available reinforcement contingencies; |

5. | The type and frequency of learning depends on the norms by which these re-inforcers are applied; |

6. | Criminal behaviour is a function of norms which are discriminative for criminal behaviour; and |

7. | The strength of criminal behaviour depends upon its reinforcement. |

A broad range of rehabilitation, prevention, treatment and behaviour modification programmes are delivered in correctional and community treatment facilities for both juvenile and adult offenders which are explicitly or implicitly predicated on social learning theory. Empirical evidence supports the effectiveness of this approach as compared to alternative methods (see Andrews and Bonta, 2003; Pearson et al., 2002).

Developmental criminology

Developmental criminology theories (DLC) adopt a dynamic rather than static approach to understanding the causes of crime and are effectively concerned with three main issues: the development of offending and antisocial behaviour, risk and protective factors at different ages and the effects of life events on the course of development. More importantly, from a rehabilitative perspective at least, DLC approaches document and explain within-individual variations in offending throughout life – an approach that is more relevant to ...