![]()

Brian Goodey

At first it was difficult to believe graffiti that appeared in view of steel framing rising over the former site of our local, Banbury, bus station, itself located on the in-filled canal dock. ‘Heritage Woz Here’ seemed less a popular protest than a contrivance waiting for camera to record it. But there it was, a modest protest against the obliteration of the town's defensive works, canal and early manufacturing industry beneath enclosures for parking and shopping, all wrapped in a pastiche of anywhere nineteenth-century-styled maltings façade devices. Or it may be a regret at the political demise of the concept of ‘heritage’ in a brave new Britain (see Goodey, 1998).

Since the mid-nineteenth century much of the UK has looked to its market towns and cities for the vitality and context that sustain life. Within the next hundred years, people moved from describing their geographical position as a village or rural location, to the proximity to town or city. Gradually the urban agglomeration drew them in – factories, shop jobs and administration providing a ticket to suburban residence within one or two generations. We are all urban dwellers now – with abstract postal codes that reinforce that relationship.

But what do we know, and care, of the urban areas within which we live, or visit? Newspaper surveys suggest that over 50 per cent of urban residents would, if given the chance, retreat to discernably rural areas, rejecting proximity, crime, grime and other presumed urban disadvantages for the, possibly false, freedom and arcadia of rural residence. Potential densification of our towns and cities, the development of ‘brownfield’ sites, and a presumption against development in the countryside or greenbelt, mean that an increased percentage of the population will be added to the residents of urban places (Urban Task Force, 1999).

Some new developments will, no doubt, be built on semi-urban locations. Estate titles will reflect field, vegetation, wildlife and village titles, often denying centuries of urban history. But when new residents receive family visitors, or instruct children, they may look to nearby urban areas which, they assume, are ‘on ice’ for their pleasure and learning.

It is this ‘pleasure and learning’ that is fundamental to the understanding of interpretation in urban areas. Interpretation should not be primarily for the overseas visitor or the informed national traveller, but for the suburban, or catchment resident, who chooses to explore the neighbouring town, not just as a retail target, but as a comfortable resource for family learning. The belief that the essence of urbanism is in the provision of effective democratic learning spaces guided such writers as Lewis Mumford, Kevin Lynch (1972) and Colin Ward (Ward and Fyson, 1973).

This local, civic seeking clientele is very seldom considered in the programmes and facilities that local authorities propose for visitors (though see Parkin et al., 1989 on the mutual visitor/resident relationship). Heritage turns its back on recency, seldom is the suburb connected to the urban centre, seldom is the twentieth- century experience that brought people to an area heralded in the themes that are explored in urban place.

We are slow off the mark. In Lowell, Massachusetts the US urban National Park, events and museum space are dedicated to introducing new immigrant groups from Asia to previous arrivals in this community mosaic. Interpretation is, and must be a gateway to civic experience – with all the value problems thus implied.

Although we have a fairly clear idea of what visitors want from urban areas, and the techniques that might be used to link visitors and place, that link is seldom made. The bottom line for interpretive investment in most towns is that local people are drawn into designing an emotional relationship with the life, history and fabric of the town, that they join organisations that sustain historic environments, events and activities, and that the sundered status of local and regional identity is repaired.

It is not really important that a local resident recognises Pevsner's Buildings of England architectural world of fourteenth-century towers and sixteenth-century monuments – or even the more impressive recent city-based volumes. Rather, that local events and features that have evolved in the townscape, many of them recently, strike a personal chord.

The best interpreter in this context is still probably the historian, allowed free rein in the local paper, using photographs, interviews and a pointed text, to link both casual and deep-felt personal experiences or memories with more rooted information (see Hayden, 1995). If that ‘historian’ is, in fact, a composite of the community, as in Stratford's ‘Eastside Community Heritage’ project in London then so much the better. This workshop project has over 5,000 participants, eighteen exhibitions, five publications and an audio documentary to its credit since 1993. With assistance and/or initiative, such local schemes can become visitor attractions as evidenced in South Africa's Township Tours, or more instructively in the communities of Barcelona.

For public or private investment in interpretive provision to work for visitors and residents there must be an underpinning of knowledge, availability and exchange that stimulates interest and resources.

Contemporary approaches and attitudes towards urbanism

There has probably been no generation where ‘the city’ has been an undisputed attraction to the entire population. Urban places have always represented power and an association with power, innovation and the risks of innovation, freedom and a context for individual expression.

Today, differing perceptions of the city may depend on income, life-style and expectation. For the young, unencumbered with family, ‘24 hour city’ vitality beckons. For the suburban family it is a quick purposeful day trip, and for the retired a chance to explore within a limited, comfortable, and often nostalgic context. Movement patterns, perceived access and lifestyle, in both physical space and in the electronic world have stimulated new patterns (and academic understandings, e.g. Westwood and Williams, 1997) and have led to a new concern for legibility (see Kelly and Kelly, 2003) after the success of a Bristol project.

In a working lifetime, those born around the Second World War have seen a remarkable sequence of urban changes. First, wartime damage, emergency housing

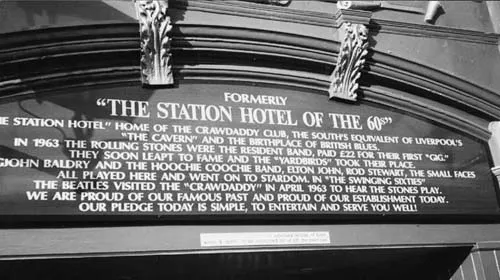

Figure 1.1 Station Hotel, Richmond. A message of rock hunters; commercial interpretation of recent cultural history

provision and belated Modern Movement central area experiments such as Coventry and Basildon, the latter one of many brave ‘new’ towns. Then phases of slum clearance, ‘decanting’ to new communities, tower blocks and peripheral estates. More Modern Movement centres trapped, as in Birmingham, by throttling road rings. From a concern with ‘Traffic in Towns’ (Buchanan, 1963), traffic became towns and from the 1970s retail vitality began to shift to ‘edge city’ leaving ‘historic town centres’ to fend as they may. It was only ministerial concern at the contrast between the brash Merryhill shopping centre and sad Dudley nearby that began to put real clout behind government's re-emphasis on traditional town centres, though as some recent public protest concerning modifications to Milton Keynes’ shopping centre have shown, modern shopping structures do have their aesthetic, as well as retail, supporters.

A wide range of scenic beauties that had been pilgrimage centres since the medieval period and mass, red book, tourist destinations since the railways, were established purveyors of the UK's heritage. Through the significance of their built form, early local interest in conservation, established events programmes (as with the Three Choirs Festival) and international visibility, cathedral, spa and early resort towns set the pace for ‘interpretation’ long before that term arrived in Britain. Even nineteenth-century guidebooks promote selected walking routes (the earlier ‘perambulations’), key buildings open to the public, official guides and an array of specialist publications. These latter offered an ecclesiastical or academic authority that is not entirely removed to this day although it now serves to distance, rather than relate, visitor to site.

Such established traditions of urban heritage presentation and interpretation were shaken by the 1975 European Architectural Heritage Year, a Council of Europe campaign in which the UK, largely through the Civic Trust, played a major part. A post-1969 European theme of cultural democratisation played through into the Campaign's concern with environmental education in schools, with participation by communities in the management of their heritage, and with telling others – interpretation – in which all could join (see Percival, 1979). This was the period of Heritage and Urban Studies Centres, of trails and walks for schools, and of industrial archaeology. ‘Architectural’ heritage turned out to be rather more – boundaries into concern for public artefacts, spaces, even meanings, began to be broken and although, as Wood (1996) has noted, the building preoccupation still survives, it is now alongside a much wider interest in context.

Since the 1970s there has been increasing recognition that all aspects of urban change, development, management … and even interpretation, require a multiagency and -area, rather than site-specific, approach. With a commitment that began long before ministries or departments were dedicated to the urban condition, the Civic Trust began its sequence of initiatives through a network of local amenity groups. Recognising the need for an holistic approach to urban revival, with interpretation as an integrated element, the Trust's Regeneration Unit (at www.civictrust.org.uk) has pioneered the development of local partnerships, an early

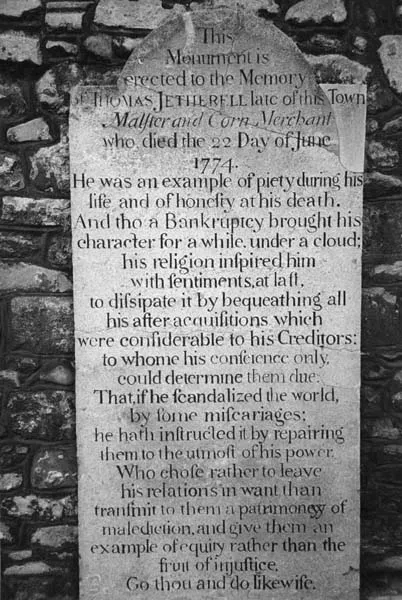

Figure 1.2 Huntingdon. Putting a life's record straight in the eighteenth-century and providing easy access to the past

example of which focused on Wirksworth in Derbyshire. The Wirksworth experience generated several important interpretive studies (including Civic Trust/CEI, 1983; Civic Trust, 1987) that developed themes and methods still evident in the Trust's approach in former industrial cities and agricultural market towns.

The ‘former’ of the previous sentence is significant. We are all aware of living in a post-industrial world where lone examples of the commonplace (such as a pot-kiln in the Staffordshire Potteries) now provide modest employment as relics. Similarly post-war generations have seen animals leave town, first for a new market on the periphery, and then for sale by video if there are any buyers. The open stalls of former market towns trade on plastic, textiles, fruit and vegetables from around the world, with the novel concept of ‘Farmer's Markets’ now (re-)introduced from North America.

The rationale for contemporary urban places is no longer a simple matter of location and centrality. Though places remain known for a single manufactured product, the firm has probably diversified and is owned elsewhere. If of value in heritage development the identifiable product may be plundered. Bird's Custard moved from down-at-heel Digbeth in Birmingham to Banbury in the great postwar decanting and is still manufactured there, though in a factory whose name has passed through several ownerships. In Digbeth, The Custard Factory is a new ‘quarter’ ve...