![]()

Chapter 1

Introducing the Electronic Brain

On November 17, 1963, members of the international design consultancy, Arup, convened at their central offices in London for a “Symposium on the Use of Computers.” 3 A decade earlier, the computer did not exist as a commercial product, but participants at the symposium were already talking about it as a necessary part of their work as technical advisors in architecture.4 By then, some members of Arup were working closely with the Danish architect Jørn Utzon on the use of computing to conduct structural calculations for the notoriously complex Sydney Opera House roofs. In that project and many that followed, the computer was burdened by enormous expectations. At the introduction to the symposium, it was heralded as “the electronic brain of popular imagination,” and its presence was treated with a mixture of excitement and anxiety.5 However, these were early days in the history of computing in architecture. The participants, mostly engineers, were only beginning to test out ideas about how the computer might change the field and their professional roles within it.

The symposium attendees contemplated the possibility that the computer might enable a new range of building designs: “The engineer would be free to give more of his time to more interesting and complicated projects.”6 They speculated that it could affect the way engineers think: “The very fact that one would be using a computer ought to make one think systematically about what one was doing.”7 They also agreed that the computer would necessitate new roles in the office – programming in particular, which was described as a “completely new job.”8 One engineer exclaimed, “If we did start using computers, special men would develop in our office,” at which everyone in attendance laughed, but they understood exactly what he meant.9 “We needed people with this specialized knowledge to act as a link between us and our problems and the computer.”10 Though still enigmatic, the new machine suggested all these possibilities at once: a new range of forms, new ways of knowing, and new kinds of professionals in architecture.11

Across disciplines, computing is redefining the relationships and conceptual distinctions that define professional work.12 In this book, I examine cultural transformations in architecture that are developing along with computer simulations. Engineers, architects, and others in the field are making trade-offs between manual traditions of design and new technologies for simulation. Historically, practitioners have developed a variety of tools and techniques for sharing imaginations, and even experiences, of buildings before they are built. In their simplest form, designers’ simulations can be personal thought experiments or mental images. But creating advanced computer simulations means engaging a network of people and powerful machines. Indeed, new technologies have profound implications for the social distribution of work: computer simulations are technologies for collective imagination.13

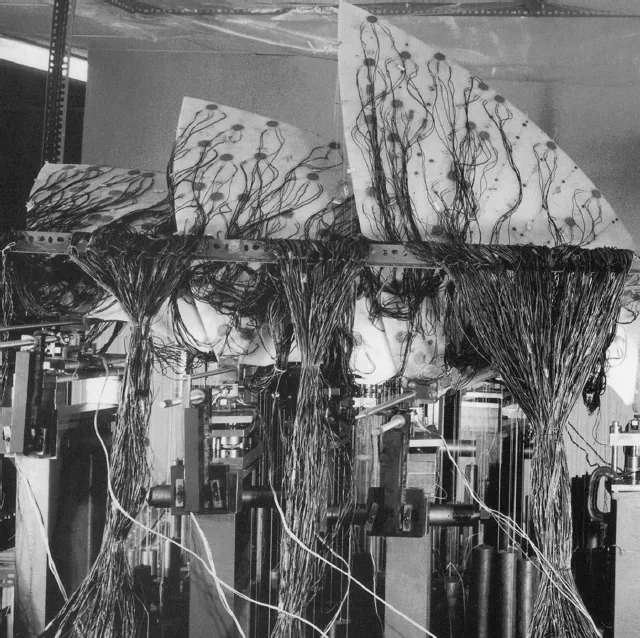

Figure 1 A hybrid structural simulation of the Sydney Opera House roofs undergoing stress distribution testing by Arup, in collaboration with the Southampton University structural laboratory.

Simulations performed on computers are used to forecast a range of behaviors in buildings: structural, visual, and acoustical, among others. They transform quantitative models of building physics into qualitative, sensory experiences. Internally, simulations contain only abstract, symbolic representations. However, they create convincing sensorial events for audiences varying from art critics to government regulators. Computer simulations have given rise to new organizations of technical and creative practitioners in architecture, making the field an important site for studying the professional implications of advanced technologies. Architecture can tell us much about the changing role of human presence in the face of increasing simulation in the workplace.

Figure 2 Ove Arup on top of Coventry Cathedral.

Assertions at the Arup symposium about the pitfalls and opportunities presented by early computers were recorded in a company newsletter.14 In particular, the newsletter makes note of the deeply held reservations and fears of practitioners: “There were agitated movements that indicated that the discussion was on the boil.”15 Ove Arup, founder of the firm bearing his name, was among the most resistant of the participants. “Design by computer was impossible,” he argued.16 “A computer has to be told what to do.” Arup’s remarks suggest that the computer and the designer are at odds. “Design is visual. You can see immediately whether something is sensible or not.” To overlook this distinction was to put the designer in jeopardy of being mechanized. Arup dramatized the implications of mechanization by making an analogy between the computerized design office and the workings of an automated farm owned by a friend of his. “Those unfortunate cows that do not conform, those that have too much or too little milk for the machine, have to be got rid of!” Ove Arup’s troubled comments highlight the degree to which the symposium was about the implications of computing for human workers.17 Many of the symposium’s attendees were fearful that the computer could come to “dominate” their lives.18 One defiantly asked, “[W]hy should a computer determine the design?”19

This historical scene captures not only apprehension, but the early hopes of practitioners in architecture – that computers would allow humans to focus on the important aspects of design and delegate the rest to machines. “It may eventually take the odious routines off our hands,” suggested one symposium participant.20 The idea that computing might take some aspects of design out of the hands of humans has since been a source of enthusiasm, but also of deep concern. Engineers and architects have struggled to define the enduring importance of human presence, judgment, and skill in design. Even today, in preparing the next generation of practitioners, they carefully consider which human capabilities might be most complementary to the computer: should students of design be trained in construction, the arts, or computer programming? Accounts from the symposium only foreshadow a wave of narratives that practitioners have since developed to think about architecture and themselves in relationship to the machine. By examining these narratives closely, we can see emerging patterns in professional life and reflect on changing notions of identity, knowledge, and form.

Boundaries of Architecture

Beyond their explicit assertions about the capacities and limits of computers, voices from the symposium carried implicit questions about the boundaries of architecture as a discipline and its stability over time. How might architecture change in relationship to computing? What, if anything, should endure? In this book, I consider what the accounts of a new class of architects and engineers can tell us about how the meaning of architecture is negotiated in the technological moment: as a set of professional identities, a system of knowledge, and a formal approach to the material world. This is a cultural study of technology. Changing human–machine–environment relationships in architecture are an indication of broader shifts in the locus of decision-making.

Since the time of the symposium, new roles have developed around the use of computers in architecture. And yet, the professional boundaries that separate architects from engineers have never been stable. Historian Andrew Saint writes of architects and engineers as siblings, “perpetually learning how to live together.”21 Today, in 2012, both disciplines use computer simulations to negotiate this relationship. Whether by mandate, or through their enthusiasm for the new medium, a number of architects are using these technologies to enrich their technical understanding of buildings, since the Enlightenment the traditional domain of engineers. Reciprocally, some engineers are using computer simulations to meet architects on their own aesthetic terms.

In the context of this continual flux, a more inclusive category is needed to account for all those who bring their aesthetic, technical, scientific, or political skills to bear in building design. I assert that these practitioners are all designers, or co-designers, in their way: they are creative, but partial, contributors to the work of imagining architecture. I use the term designer liberally, not to whitewash the differences between practitioners, but rather to emphasize the creative contributions of each and to forestall ready-made attributions of authorship in new configurations of humans and machines.

Understanding the implications of computer simulations requires a broad view of how they affect systems of relationships. It is not enough simply to talk about these technologies in terms of one person at a machine. In addition to many varieties of architects and engineers, those participants who are seemingly on the fringe of design – including regulators, contractors, technology developers, and researchers – are all designers in their own right. These participants have found diverse ways of staying in the loop and maintaining influential roles in the field. However, this book does not seek to tell the stories of all designers. That is a much more ambitious project. Instead, it focuses on an emerging faction of practitioners, those who define themselves and their work explicitly in relationship to computer simulations. Their stories offer crucial insights into the rapidly changing social and technological system of architecture practice.

Theorist Herbert Simon may have defined design in its broadest sense in The Sciences of the Artificial, as any activity where an existing state is transformed to a preferred state.22 In practice, the activities labeled design and the people who call themselves designers are not nearly as broadly constituted. Therefore, for the sake of this book, I have had to establish some limits on what I consider to be design. However, future studies would do well to question the boundaries that I draw here.

In architecture, which deals with the large-scale transformation of human environments, I take design to be the manipulation of representations of environments: plans, sections, models, diagrams, and other “intermediary objects.”23 Computer simulations are also intermediary. They are part of the evolving toolkit that practitioners use to establish virtual sites in which designs can be tested before they are built. They exist between conception and construction, but also between professional groups. However, computer simulations can be different things to different groups: tools for exploration, verification, reflection, or simply communication. In this sense, a definition of simulation is not easily held down. In fact, as Wittgenstein observes, words only gravitate toward stable meanings in dialog, and even then, personal interpretations come into play. The search for simulation’s meaning in practice is a kind of “language game.”24 The term simulation, as applied in everyday design settings, is only as well defined as it needs to be to enable an exchange.

While later in the book, I will explain the kinds of exchange that simulations enable, I employ the term now in reference to a type of representation that maps closely onto how people perceive their environments. The simulations addressed in this book are not the abstract models that architects make for themselves as form-finding devices, nor the exclusively numerical spreadsheets that engineers create routinely. Those are important representations indeed, but they are not my focus.25 Instead, I concentrate on the computer simulations that motivate broad consensus through virtual experiences of alternate possible realities.

There is also a history to the separation of design (the transformation of representations) from construction (the transformation of materials), which has technical, economic, and deeply professional motivations that echo some of the themes highlighted in this book.26 However, rather than consider people who make buildings, I focus on people who make building representations. But even when these distinctions are taken for granted, divisions proliferate. Professionals jockey for jurisdiction over the means of representation. Creative and technical tasks are differentiated in inconsistent ways. From project to project, architects and engineers must look for ways in which they can represent architecture in order to gain a professional upper hand. Conceptions of architecture, its parts, practices, and purposes, are under continual negotiation through representations. Computer simulations become players within these negotiations. As such, I am attentive to the ways in which professionals use simulations strategically. Tracking contemporary professional narratives reveals how computer simulations are used to reframe architecture for purposes of professional positioning.27 Such technologies are configurations of both materials and human relationships.28 We need to assess which claims about computing suggest new configurations for designers, and which ones serve to maintain old hierarchies and disciplinary boundaries.

By the time of the 1963 symposium, Ove Arup and his colleagues had already started to define themselves in relation to the perceived capabilities of early computers. Yet they were only beginning to test out ideas about how to appropriate computing to reframe architecture. Today, computers are being adopted by designers to make new claims about buildings. Architects are adopting visualization to image architecture with unprecedented realism. Acousticians are using auralization to help their clients listen to buildings before they are built. Structural engineers are using finite element analysis to discover a new range of optimal shapes.

Many designers have reflected on the diffusion of computing into architecture.29 However, they have done so in terms which are predominantly instrumental. When theorists of architecture write about the implications of the digital, they often miss the changes that redefine the profession at a cultural level: how good form is assessed, how identity is professed, and how knowledge is produced.30 The material products of architecture, the focus of much writing in the field, reveal little about forms of underlying professional life and how they are changing.31

Today’s powerful computing systems represent the latest in a series of technologies that practitioners have adopted, sometimes reluctantly, as a means of further defining both their professional relationships and their approach to architecture. Practitioners have long known that creating a place for themselves within the professional world means negotiating relationships with new technologies and through them. The history of technologies for representation in architecture has been well documented by scholars, including Mario Carpo and Robin Evans, who both write about architecture’s shift from geometry to numeracy in th...