eBook - ePub

Environment, Growth and Development

The Concepts and Strategies of Sustainability

- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

First Published in 2004. Environment, Growth and Development offers a unique analysis of sustainable economic growth and development and the implications for policy and planning at the local, national and global scale.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Environment, Growth and Development by Peter Bartelmus in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

What On Earth Is Wrong?

This chapter describes the main concerns with development, growth and the environment. An overview of international strategies and approaches reveals large-scale failures in all those areas. Selected indicators of the state and trend of the environment try to answer the questions of what and how much is wrong with the planet. The chapter concludes that the latter (how much?) requires integrated databases and aggregated indicators as common yardsticks of environment and development.

1.1 Development and environment: from global discussion to global frustration

Lost decades of development

Economists and parliamentarians agree that the ‘past decade has been a cruel disappointment’ to developing countries (The Economist, 23 September 1989)—indeed ‘a lost decade of development’ (Parliamentarians for Global Action 1990). With a few exceptions of developing countries in South-east Asia, the rich countries got richer and the poor ones poorer.

Before attempting to determine who are the winners and losers in the global strife for growth and development, it is useful to recall what is commonly understood by economic growth and development. Development is generally accepted to be a process that improves the living conditions of people. Most also agree that the improvement of living conditions relates to non-material wants as well as to physical requirements. Development goals that call for the increase of human welfare or the improvement of the quality of life reflect this agreement.

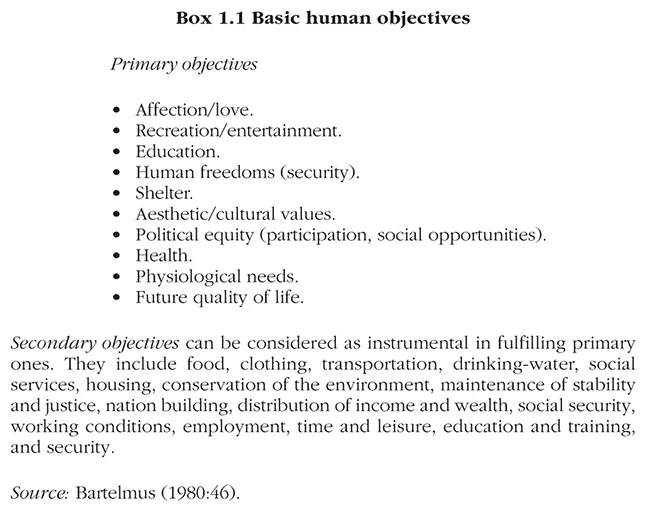

Quantifiable definitions of these concepts are needed for measuring progress towards development goals. A typical starting point has been to break down the overall objective of human welfare into sub-objectives or targets. The difficulties involved are described by Bartelmus (1980:40 et seq.). Box 1.1 offers a tentative list of general (primary) human objectives, condensed from a variety of publicly proclaimed social objectives. Subjective

value judgements are involved in such a list. Any further breakdown would be even more arbitrary as human preferences for more specific ‘secondary’ objectives or desirables (as enumerated in the box) vary significantly among individuals and through time and space.

Generally, applicable policies and strategies to meet such objectives are as difficult to identify as the objectives themselves. Such policies must weigh trade-offs between goals and values within changing socio-economic conditions. In most developing nations, low levels of living and productivity are accompanied by high levels of population growth, unemployment, international dependence and a predominantly agrarian base to the economy. Based on these common factors, some international agreements on development strategies have been reached. However, those agreements had to be revised repeatedly in view of considerable failures of the proposed strategies at the national level.

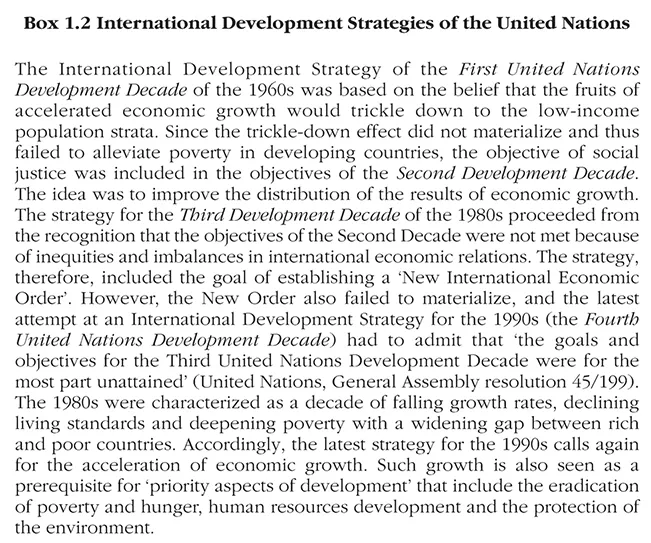

As indicated in Box 1.2, this stark picture of development seems to have brought back a focus on economic growth, the central theme of the First International Development Strategy in the 1960s. The Fourth Strategy for the 1990s advocates the revitalization of economic growth while paying some attention to other ‘aspects’ of development. To some extent, this return to economic growth strategies might have been brought about by the absence of a widely accepted indicator of development. The

economic-growth concept of development utilizes Gross Domestic or National Product as a concise measure, usually in per-capita and real (price-deflated) terms. It is generally acknowledged, however, that economic growth is at best an ‘essential’ (World Bank 1992:34) or a ‘mere’ (UNDP 1992b: 2) means of development rather than an end in itself.

For a multidimensional concept of development, as expressed in lists of human objectives or needs, it is more difficult to find a similar aggregate measure. As shown in Chapters 2 and 3, aggregate development indicators and the correction of national accounting aggregates to obtain measures of economic welfare are still in their infancy; they cannot (yet) replace national or domestic product, which provide an overall insight into a country’s productive capabilities and hence into one of its major sources of national welfare. Nonetheless, some attempts at categorizing countries in terms of overall ‘development indices’ have been made and can be compared to rankings of countries in terms of conventional domestic product or national income.

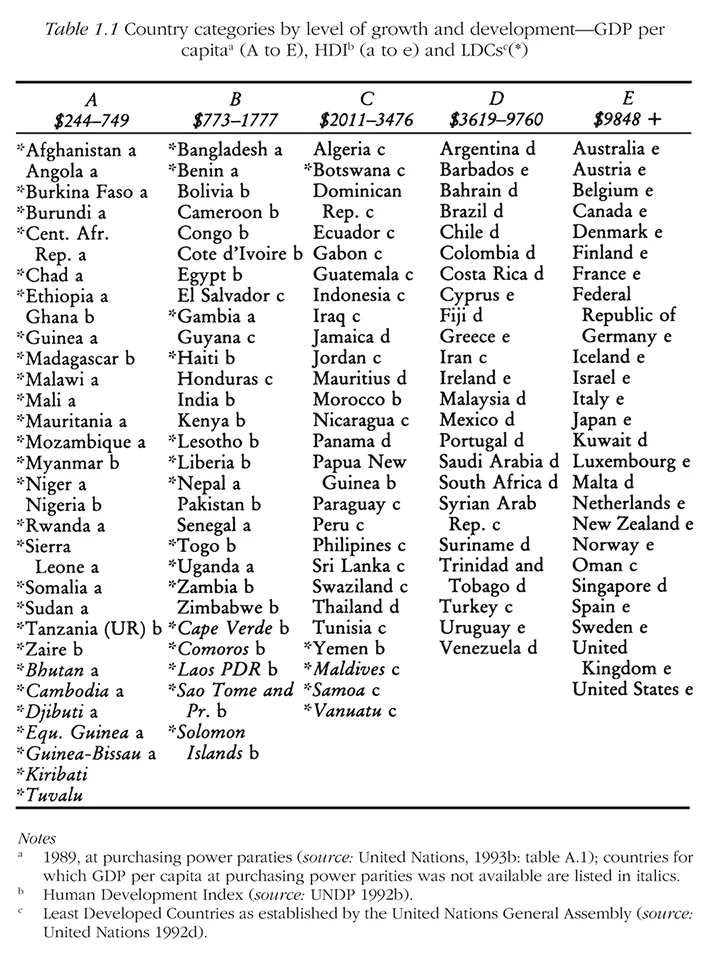

Three approaches to classifying countries according to their stage of development are compared in Table 1.1. The basic grouping is determined by the traditional measure of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita at purchasing power parities rather than conventional exchange rates (United

Nations 1993b). Countries are grouped into five categories from A for the poorest and E for the richest countries. This ranking by economic growth is contrasted with a broader development measure, the Human Development Index (HDI), developed by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP 1992b). The Index combines indicators of national income, life expectancy and educational attainment. It reflects, therefore, a relatively arbitrary selection of factors considered to contribute ‘significantly’ to development. A more politically determined categorization of Least Developed Countries (LDCs) is established by the General Assembly of the United Nations. LDCs are countries with low GDP per capita, a low level of the ‘physical quality’ of life (life expectancy, calorie supply, school enrolment and adult literacy) and lack of economic diversification. Those countries are indicated with an asterisk in Table 1.1.

LDCs are closely correlated with the level of economic growth (categories of A and lower ranking B). Notable exceptions are a few small island developing countries (Maldives, Samoa, Vanuatu) where the low diversification aspect (and dependence on development assistance) (United Nations 1992d: 61) has prevailed in the selection. In terms of the broad categories (A to E and a to e), there seems also to be a close relation between economic growth and human development. One major exception is the muted significance of high-level income in oil-rich Middle East countries in the HDI: those countries lose up to 37 ranks (in the original tables) due to the reduced significance of high incomes in the HDI.

Environmental doomsday and international reaction

It is worthwhile to recall the ups and downs of the environmental movement because there seems to be some risk of recurrence of early (over)reaction to environmental problems. Conspicuous pollution incidents in the 1960s and neo-Malthusian responses to demographic and economic growth led to the appearance of environmental doomsday literature. Titles like The Death of Tomorrow (Loraine 1972), Silent Spring (Carson 1965) or Blueprint for Survival (Goldsmith et al. 1972) are indicative of the environmental mood in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The use of a seemingly objective computerized global model was probably responsible for provoking much of the widespread attention to the Club of Rome’s Limits to Growth, (Meadows et al. 1972). The model predicted a ‘rather sudden and uncontrollable decline in both population and industrial capacity’ within the next century if current growth trends remain unchanged. Zero (or even negative) growth was advocated to avoid the disastrous consequences of transgressing the physical limits of the Earth’s resources.

Another pessimistic conservationist view focused on the preservation of ecosystems and endangered species to the neglect of socio-economic conditions and consequences. Examples of this view are Curry-Lindahl’s Conservation for Survival (1972) and Caldwell (1972) who purports to defend Earth against the ‘unecological animal’ man.

Those policies could not be accepted by countries that were still in the early stages of socio-economic development. For them, economic growth appeared to be more important than concern about a few endangered species of wildlife. Only affluent countries were seen to be able to afford the luxury of diverting some of their wealth to environmental protection. Moreover, the high and wasteful consumption levels of the industrialized nations placed a large stress on the resources of developing countries. Proclamations of global solidarity for spaceship Earth were thus met with suspicion and distrust by developing countries. The only view rich and poor countries seemed to share was the conviction that environmental conservation and economic development were in conflict with each other (UNEP 1978). It is the merit of the international community that it has opened a dialogue on the environment-and-development issue between developed and developing countries through a number of international seminars and conferences.

The Secretariat of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment organized a seminar on development and environment at Founex, Switzerland (United Nations Conference on the Human Environment 1972). The seminar concluded that environmental problems do not only result from the development process itself but also from the very lack of development. Poor water, inadequate housing and sanitation, malnutrition, disease and natural disasters were cited. The term ‘pollution of poverty’ was later coined to describe this aspect of the environmental question. Consequently, environmental goals would provide a new dimension to the development concept itself, requiring an integrated approach to environment and development. The United Nations Conference on the Human Environment (United Nations 1973) endorsed these principles, emphasizing that environmental and developmental goals could be harmonized, inter alia, by the wise use of natural resources. The Conference also established a small (but rapidly expanding) secretariat, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) to facilitate and monitor the implementation of the Conference’s action plan.

In the wake of the energy crises in 1973 and 1974 and of the declaration of a New International Economic Order in 1974 (see Box 1.3), a joint UNEP/UNCTAD Symposium at Cocoyoc attempted to integrate a general assessment of development goals with new ideas in the field of environment. It was recognized that the failure of society to provide a safe and happy life for all is not one of ‘absolute physical shortage but of economic and social maldistribution and misuse’. Hence, the Symposium advocated a strategy of satisfying first basic human needs, with due consideration for global environmental risks or so-called ‘outer limits’ (UNEP and UNCTAD 1974). The basic-needs approach was taken up and widely publicized by the Programme of Action of the 1976 World Employment Conference. The Programme recognized food, shelter, clothing and essential services such as safe drinking-water, sanitation, transport, health and education as basic human needs and requested that basic-needs policies become an essential part of the United Nations Third Development Decade Strategy (ILO 1977).

Since then, international statements have tended to dissociate themselves from the basic-needs approach. Developin...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of tables, figures and text boxes

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- 1 WHAT ON EARTH IS WRONG?

- 2 ACCOUNTING FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT

- 3 ENVIRONMENT AND DEVELOPMENT—A MATTER OF SUSTAINABILITY?

- 4 PLANNING AND POLICIES I: SUSTAINABLE GROWTH AND STRUCTURAL CHANGE

- 5 PLANNING AND POLICIES II: SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT

- 6 OUTLOOK: FROM NATIONAL TO GLOBAL COMPACTS

- References

- Index