eBook - ePub

Do Political Campaigns Matter?

Campaign Effects in Elections and Referendums

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Do Political Campaigns Matter?

Campaign Effects in Elections and Referendums

About this book

This book, in bringing together some of the leading international scholars on electoral behaviour and communication studies, provides the first ever stock-take of the state of this sub-discipline. The individual chapters present the most recent studies on campaign effects in North America, Europe and Australasia. As a whole, the book provides a cross-national assessment of the theme of political campaigns and their consequences.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Do Political Campaigns Matter? by David M. Farrell,Rüdiger Schmitt-Beck in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politica e relazioni internazionali & Campagne ed elezioni politiche. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Studying political campaigns and their effects

Rüdiger Schmitt-Beck and David M. Farrell

Political campaigns are treated as occasions of immense importance by politicians, and never more so than today. In recent decades political actors of all sorts – parties and candidates, governments and other political institutions, lobby groups, social movements and other kinds of citizens’ associations – have increasingly come to view political campaigning as an essential supplement to their engagement in the process of policy making. By investing ever more efforts and resources into political campaigns they seek to mobilize support among the mass public, to persuade citizens of their causes, and to inform the citizenry about public policies and political activities. So far as the practitioners are concerned, such campaigns matter a great deal. Those waging campaigns firmly believe that these efforts help them to achieve their political goals and thus count in the political process. Each year, literally billions of dollars are spent, mostly in election campaigns (at all levels), but increasingly also in other kinds of campaigns, such as referendum campaigns, policy-related information campaigns, or image campaigns. The sophisticated (and thereby costly) services of specialist agencies and campaign consultants are engaged; candidates are sent on television training courses and are suitably colour-coded; glossy literature, advertisements of many forms and items of campaign gimmickry are produced. While parties, candidates, interest groups, governments, media and (some) voters are apparently strongly convinced of the notion that campaigns do indeed matter, the collective views of the academic community can perhaps best be summarized by the word ‘undecided’.

The issue is certainly of relevance to a number of fields in political science. There have been countless studies in the voting behaviour literature on the ingredients that voters take into account when deciding which party or candidate to vote for at elections, or which proposal to support at referendums. But with few exceptions there has been little analysis of how these factors are connected with the communication activities of political parties and other campaign organizations. There is also a large body of literature in the area of communications studies, examining the effects of the news media's political reporting on the opinions and attitudes of their audiences during campaign periods. In a number of cases these show how media reporting to some degree reflects the campaign activities of political actors. But the media are by no means the only channel through which campaigns reach their audiences. While inquiries into the effects of political campaigns cannot ignore the mediating role of mass communication, equally they cannot restrict themselves to looking only at the media. Finally, there is a growing body of research in party sociology (and also in the study of social movements) on how political organizations plan and implement their campaigns. This usually starts from the premise that campaigns are important, although there have been few attempts to prove this assumption empirically.

To be sure, recent years have seen an increased effort to go beyond the limitations of these strands of research with the aim of producing firmer conclusions about whether and how political campaigns matter. A fairly large range of specialist studies of campaign effects have accumulated, although these have tended to be very specific in scope. Most have dealt only with election campaigns – zeroing in on a particular campaign in a particular context – and their findings, therefore, have tended not to be easily generaliz-able. Furthermore, the study of campaign effects has been predominantly focused on a small number of national contexts, above all the United States, with a much more sporadic coverage of trends in Britain and a few other cases.

This book represents the first cross-national effort to take stock of the state of this sub-discipline. The nine chapters which follow examine campaign effects in a range of different national contexts, using a range of different methodologies. In this introductory chapter we set the scene for what is to follow. We start, in the first section, by outlining the field of study of campaign effects, setting out a definition of campaigning, and reviewing the types of campaigns that can be included in this area of analysis. The subsequent sections concentrate on campaigns for elections and referendums, exploring the core features of contemporary campaigns and discussing the range of likely ways in which these campaigns might be said to have some influence. Finally, we provide a short section reviewing the main trends in the study of campaign effects, before concluding with an outline of the rest of the book.

The rise of campaign politics

Campaigning is a core feature of the political process in contemporary democracies. Election campaigns see parties and their candidates wage battles for votes and political office. Referendum campaigns see proponents and opponents of the relevant issue seek to steer the vote in their preferred direction. Issue-based campaigns see government agencies or interest groups attempting to have an issue or policy placed high on the political agenda, and to have it favourably framed in public debate. Image campaigns see efforts to paint the public perception of some political actor in a more favourable light. In the past few decades campaigning has assumed increasing relevance as a mode of political mediation, in part reflecting the growing volatility in the electoral process, in part also reflecting a general shift towards issue-based politics and a greater emphasis on alternative modes of political participation. If the first of these indicates a greater role for ‘policy mediation’ – consisting of top-down flows of strategic communication originating from the political elite – the second is more suggestive of a process of ‘interest mediation’, in which, in particular, the political elite face ever more competition for agenda setting from interest groups and lobbying organizations (Edelman 1985, 1988; Sarcinelli 1987, 1998; Röttger 1997; Bentde et al. 2001).

Campaigns occur not only in the political realm; they are increasingly important in all walks of life: for instance, a company mounts an advertising campaign to promote its product; a charity seeks to raise money for an overseas aid programme; a city engages in ‘city marketing’ in order to attract investors and new businesses. Since the focus of this book is specifically on political campaigns, it is useful to start with a basic definition. The objective of a political campaign is to influence the process and outcome of governance. It consists of an organized communication effort, involving the role of one or more agencies (be they parties, candidates, government institutions or special interest organizations) seeking to influence the outcome of processes of political decision-making by shaping public opinion. Political actors are campaigning because they hope that the support of the public, or of relevant segments of the public, will help them to promote their political causes. Often such public support, at least in the short term, may help political actors to attain their goals, most notably in those cases where the public itself takes the relevant decisions, as in elections or referendums. However, campaigns are also gaining importance as a tool of the political craft in many other scenarios in which favourable opinions on the part of significant publics are believed to lend causes legitimacy, thereby furthering their chances of success. This is shown, for instance, by the case of public interest groups striving to elevate particular issues on to the decision-making agenda, or by the case of government agencies seeking to produce legitimacy for policy programmes during the implementation phase. To such ends, these political actors mobilize strategic resources of varying kinds and to varying amounts. They do so within institutional and situational contexts that may entail both constraints and structures of opportunity (Farrell 2002).

What the agency is seeking to influence can vary widely. If it is a political party fighting an election campaign, it may want to maximize the number of seats it wins, or, indeed, it may as, say, a Green party, be seeking to influence the political agenda. In both cases the party's target for influence is voters (though, in the latter case, the expectation is that any influence over voters will also have a bearing on the attitudes of the established political actors). In the case of a special interest group during a referendum campaign, its focus will be on achieving victory for its side, and again the principal target will be voters. By contrast, in the case of a special interest group seeking to raise the profile of an issue by placing it higher on the political agenda and framing it in particular ways (e.g. in the hope that a party might take it on as an issue, or that a referendum might be called) the principal target is the established politicians, with public opinion functioning as the connecting hinge (Schmitt-Beck 2001).

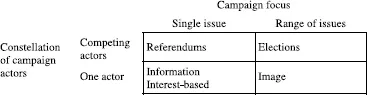

Figure 1.1 A typology of political campaigns.

Figure 1.1 attempts to simplify the discussion somewhat, by reducing the wide range of different campaign scenarios to a simple two-by-two typology based on the constellation of actors involved in the campaign and the focus of the campaign. This suggests four main types of political campaigns, two of which are considered in this book. The first, and most obvious, type is the election campaign (dealt with in Chapters 2–8) which is characterized by a set of competing actors (political parties/candidates) each campaigning on a range of issues (as well as a focus on candidate and party image), with the principal goal being electoral success. To be sure, this is an ideal-typical simplification, as, for instance, in the case of certain minor parties, particularly those with a strong ideological bent, electoral gains may actually be given a lower priority. In addition, by waging campaigns, parties may also seek to serve internal party purposes, like maintaining party unity, attracting new members, fund raising, nurturing potential coalition links and so on. Yet success at elections, and the chance to occupy government positions that it provides, is clearly the core objective of parties and their candidates (Downs 1957; Weber 1980 [1921/22]: 840–1; Schumpeter 1994 [1942]). Second, there are referendum campaigns (dealt with in Chapters 9–10), which share with election campaigns the fact that there are competing sets of actors (although here there is greater likelihood that not all of these actors are parties), but in this case the campaign is focused on just one issue, and there is not even the ‘distraction’ of a political candidate.

Third, there are single-issue campaigns unilaterally launched by just one actor. Such campaigns are often implemented by government agencies, in order to inform the public (e.g. ‘drink and drive’ campaigns), and/or to mobilize support and raise acceptance of particular policies. Notable examples are the campaigns on privatization policies and the poll tax in Britain, launched by the Conservative government in the 1990s (Newton 2000), or the campaign of the European Central Bank to ease the implementation phase of the euro. In the same category we find also interest-based campaigns by pressure groups aimed at influencing the political agenda and the way political problems are framed; a prominent example with transnational reach are the activities of the anti-globalization movement and its member organizations. This category shares with referendum campaigns the focus on a single issue at a time. A distinguishing feature of this type is that there is generally just one actor in the fray: a government department, perhaps a religious or consumer organization, or other public interest groups and lobby organizations. While starting with activities launched by just one actor, such campaigns may easily lead to competitive battles for public opinion as other actors, feeling challenged by the points of view raised by the first actor, wage counter-campaigns. Finally, completing our typological matrix, there are image campaigns. These are also launched by single actors, but may involve a range of issues, wrapped together with various kinds of emotional appeals. Their purpose is to raise the public esteem of the actor in question. An example is the campaign of the Conservative government to improve the ‘uncaring’ and ‘cold-hearted’ image of Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher (Newton 2000). These latter two types of campaign are dealt with only in passing in the remainder of this chapter, since our focus is on campaigns for elections and referendums.

Political campaigning here and there, then and now

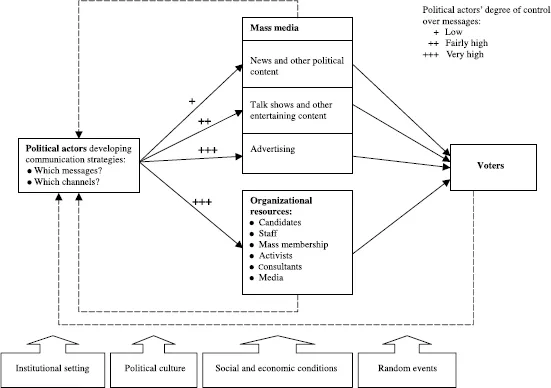

Election and referendum campaigns can be seen as complex processes of purposive political communication that are essentially ‘top-down’, originating from campaign organizations like parties, candidates’ support organizations, government institutions or interest groups, and aimed at the mass public in its entirety or at specific ‘target’ segments. Yet, as visualized in Figure 1.2 by means of broken arrows, campaigns also entail ‘bottom-up’ components, since political actors constantly seek feedback by monitoring their target audiences in order to assess whether their strategies are working. Election returns, for instance, are routinely interpreted as indications of the quality of election campaigns. In addition, campaign organizations increasingly rely on techniques for the systematic observation of public opinion like surveys or focus groups to plan their strategies and calibrate their campaign instruments (Rose 1967; Kavanagh 1996). The mass media are also utilized as sources of feedback. Guided by the assumption that the media are powerful agents of influence, political actors constantly screen their reporting in order to anticipate what media audiences think. In addition, when several actors wage competing campaigns each of them may use the media as a source of intelligence about its opponents.

Ultimately guided by their political goals, but taking into account their assessment of the specifics of the current situation, political actors like party leaders or candidates develop strategies for their campaign communications. They must determine which messages may be most helpful to achieve their goals, and which channels to use to get these messages across. Since material and non-material resources may be available in varying amounts to different political actors, but are in any case always inherently limited, decisions must be taken about how these are best to be allocated. Difficult problems must be solved. Should one wage an expensive advertising campaign, or rather rely on the manpower of the organization's rank and file? If advertising money is laid aside for ‘paid media’, should it be spent on a large number of newspaper ads, or on a few television spots? Should one seek the costly help of a prestigious advertising agency, or economize by financing training seminars for local volunteer canvassers? Such questions are not easy to answer, and a lot of experience and expertise, but also creativity and perhaps even luck, are necessary to arrive at the right answers.

Figure 1.2 A model of campaigning.

Source: Adapted from Schmitt-Beck and Pfetsch (1994: 117).

The mass media are a very important channel of campaign communications, and increasingly so, but they are usually not the only means by which campaigners can reach their addressees. In election campaigns, most political actors traditionally rely on their own organizational resources. Only a few actors, like the independent presidential candidate Ross Perot in 1992, rely exclusively on the media to communicate to voters. But for other candidates it is still common to travel the length and breadth of the country, delivering speech after speech on public squares and in town halls, and meeting citizens in the back rooms of smoke-filled pubs. Local voluntary activists canvass the neighbourhood and seek face-to-face discussions with their fellow citizens at street stands. They are also a human resource important for organizing the local rallies for candidates and party leaders. Entering the age of mass parties, these organizations equipped themselves with permanently employed professional staff, among whose most important organizational tasks were activities connected with campaigning. In recent years, in addition to the organizations’ own personal resources, the services of hired specialists have been quickly gaining importance for all kinds of sub-tasks within the increasingly complex business of campaigning. Political consultancy has become big business in the United States, but to some degree it is gaining ground in most contemporary democracies, leading to increasingly professionalized campaigns (Farrell and Webb 2000; Farrell et al. 2001).

In most countries, the days are long gone when parties owned their own general readership newspapers and thus had at their disposal a convenient medium of campaign communication. The party press, where it still exists, has mostly turned into an instrument of internal communication. Yet nowadays modern communication technologies offer new opportunities for campaign organizations to free themselves to some degree from the constraints that arise from the necessity to rely on independent media to get their messages across. Within a few years political actors’ use of the internet has spread extensively. Most parties as well as government agencies and all kinds of other citizens’ associations now operate professional websites as a means of circumventing the filters of the news media to communicate directly with voters (Bieber 1999; Margolis et al. 1999; Norris 2002).

Naturally, for political actors it is important to exert as much control as possible over the ways their messages are conveyed to the electorate (Zaller 1998). As far as they can use their own organizational resources for that purpose, thus directly communicating with voters, they enjoy considerable (though perhaps still not full) autonomy in designing and disseminating their messages. Constraints may arise to the degree that leaders are dependent on their organization's activist members. An important part of campaign strategies, therefore, focuses on efforts to mobilize the membership. This implies that political actors must be careful not to offend their followers by proposing unpopular ideas or violating esteemed traditions. In this sense at least, members can be a force of inertia, limiting the freedom of action of the leaders. Yet, despite all the changes in how campaigns are waged, political organizations continue to be one of the most important channels for political actors to reach voters directly. Another channel of direct communication with the electorate is advertising. Through printed advertisements, billboards or television spots political actors are able to convey (almost) any message they like to (almost) anyone they like, up to the limits of the audience's attention, and their personal budgets.

Advertising is expensive, especially on television. Therefore, political actors have a strong incentive to supplement these ‘paid’ media by ‘free’ media (in Table 1.1 we refer to these, respectively, as ‘indirect’ and ‘direct’ media), through appearances in the news and other political programmes on television as well as in the press (Salmore and Salmore 1989). Carefully staged ‘pseudo-events’, cus...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Routledge/EGPR Studies in European Political Science

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Figures

- Tables

- Contributors

- Series editor's preface

- Preface and acknowledgements

- 1 Studying political campaigns and their effects

- 2 Calculating or capricious?: The new politics of late deciding voters

- 3 When do election campaigns matter, and to whom?: Results from the 1999 Swiss election panel study

- 4 Campaign effects and media monopoly: The 1994 and 1998 parliamentary elections in Hungary

- 5 Priming and campaign context: Evidence from recent Canadian elections

- 6 Candidate-centred campaigns and their effects in an open list system: The case of Finland

- 7 Post-Fordism in the constituencies?: The continuing development of constituency campaigning in Britain

- 8 Do campaign communications matter for civic engagement?: American elections from Eisenhower to George W. Bush

- 9 Referendums and elections: How do campaigns differ?

- 10 Public opinion formation in Swiss federal referendums

- 11 Do political campaigns matter?: Yes, but it depends

- Bibliography