1

Beginnings

Wednesday lunchtime at the Albion Children’s Hospital. A heavy autumnal sky dulls the out-patient area, where Susan Johnson, her husband Matthew and their six-week-old son Daniel are waiting to see the doctor. An abandoned newspaper on the chair beside Susan carries the headline ‘NHS Rocked by Organ Scandal’. She doesn’t want to read it, but needs something to take her mind off the wait. She chats briefly to the mother of a very noisy toddler who has already had two tantrums in the past half hour and looks set to launch into a third. Somehow this makes things worse. Susan can’t help thinking that the other little boy looks so well, and she’s sure that there’s something seriously wrong with Daniel. Once again, she pulls out his baby book and tries to convince herself that his painfully slow weight gain is just down to his stormy first weeks in hospital. That it will soon pick up.

In a small room across the corridor, Dr Sebastian Hill is feeling nervous. He knows there’s a family waiting to see him—the Johnsons—but he stalls for time by refiling an X-ray report that is out of sequence. All in all, it’s beginning to feel like ‘one of those days’. He was even late starting this clinic because he was delayed on the ward helping a junior colleague put a drip up on a child with severe asthma. Then things got progressively more behind while he waited for an interpreter for his first patient and spent some time chasing up an important test result on the next patient. Now he’s about to tell the Johnsons that their son has a serious life-shortening illness, and the specialist nurse who would normally have been there to break the news with him has called in sick. Sebastian is just one week into his first teaching-hospital registrar job, and he knows he should probably ask his consultant for help. But after calling her twice already this morning, he desperately wants to make a good impression by getting through the rest of the clinic independently.

The sound of a drill starts up again outside, from the site of the new hospital wing. Daniel starts to cry. Matthew tells Susan it’s outrageous that the wait’s so long. Sebastian closes the window to try to block out at least some of the drilling noise before calling the Johnsons in, though it’s unbearably muggy since the heating goes automatically to high in September. Glancing across at the new building, blue tarpaulin flapping from its scaffolding, Sebastian wonders fleetingly whether sinking eight million pounds into a gene-therapy centre is really the best use of resources. Surely what the hospital really needs is more nurses, a better cleaning service, more interpreters to translate for those who don’t speak English and a new computer system in Outpatients. Gene therapy doesn’t seem very utilitarian, set against all that. But that’s not his problem right now. His more immediate concern is the anxious family on the other side of the consulting-room door. So he washes his hands, glancing in the mirror as he does so, straightens his tie and gathers up Daniel’s notes. Then he walks into the reception area to find the Johnsons.

It’s about people

The NHS (National Health Service) occupies a curious position in the hearts and minds of the British public. It is, at the same time, both one of its proudest institutions and a ‘political football’; an institution in which everyone has a stake, and about which everyone has an opinion. Health care is everybody’s business.

The recent high-profile cases and increasing politicisation of the Health Service have made its public face too often one of errors, waiting-list crises, ‘organ scandals’ and managerial obfuscation. Yet, despite the media interest and spin associated with these events, public confidence in doctors remains higher than in any other professional group. Most service users remain positive about their experiences of health care, and NHS staff report high personal satisfaction with their jobs.

How can these apparently differing perspectives be reconciled? The answer lies with the people who sit at the heart of this book: the people who use the NHS and who rightly expect to be seen by health-care staff who communicate effectively, perform their roles competently and treat them with respect; and the people who staff the NHS and face the challenge of providing that health care within the financial and organisational constraints of a large and complex system. While government policy, funding arrangements, policy statements and star ratings are impersonal, the people at the end of the waiting lists are real. What matters—and what ultimately leaves a lasting impression on both parties—is the interaction that takes place between the patient and the doctor, nurse, physiotherapist or pharmacist responsible for their care. The vast NHS machinery that brought them into a room together suddenly fades from view, and the success or failure of the interaction then moves into the hands of those individuals.

The impetus to write this book arose from a dramatic and unique approach to personalising these issues in order to improve patient care at Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children (GOSH). Called ‘Snakes and Ladders: Learning about the Ups and Downs of the Patient Journey’, it was a new departure in medical and multi-professional education. Across the country and, indeed, the world, doctors are familiar with the hospital ‘Grand Round’: a rite of passage in which juniors present a clever diagnosis, a cutting-edge piece of research, the latest information about their subject to an audience of peers and seniors. One lunchtime in September 2002 (while doubtless countless families waited just like the Johnsons and doctors like Sebastian tried to prepare themselves for a difficult consultation), the Grand Round was reborn. Professional role players were brought into the hospital lecture theatre to play out the story of one fictional young patient from birth, through his illness, to wherever his adolescence and the tale led. Staff participated in, and were encouraged to influence and criticise, this hour-long monthly drama, which was aimed at all ‘front-line’ clinicians, managers, secretaries and a variety of other support staff—everyone working at GOSH—because improving the experience of patients and families depends on them all. The audience was given the opportunity to work through the practical, clinical, ethical and emotional challenges confronting the Johnsons, Sebastian Hill and the other staff involved in Daniel’s care. And, despite the fact that staff had their fill of the day-to-day drama of hospital life in every moment of their working day and could top up, if desired, with an extra fix of Casualty or ER in the evening, they came in droves to spend one lunchtime a month keeping up with the Johnsons. It was a far more effective way of communicating important issues than reading the latest policies on drug safety, consent or bed management.

But it is not enough to have just played out the issues with the staff who came into the lecture theatre and with visiting colleagues from district general hospitals and primary care. We also need to extend the messages to staff working across the NHS, whether in paediatric settings, in adult care, in acute trusts or in the community—because the core principles of patient-centred care are important to us all. And if the messages are about patient-centred care, it is crucial that we also share them with the many Daniels, now in their teens or young adulthood, and with their parents, grandparents, siblings and friends. With the many people at all ages and stages who use the NHS on a day-to-day basis and who wish to understand what makes it tick, how to get the best out of it and how to help improve it. This book thus replays the journey that we at GOSH, and frequent professional external visitors, followed on stage, in debate, on-line and through printed back-up material after each episode.

It’s about time

Daniel Johnson was ‘born’ on 1 August 2002, shortly after the NHS celebrated its fifty-fourth birthday. Through the greater part of that half century, health care in general and the medical profession in particular operated through a benevolent paternalism, largely accepted by the public because of the perceived expertise and dedication of its practitioners.

The first seeds of cultural change started to emerge through Thatcher’s consumerist approach of the 1980s. The Labour Government that gave birth to the NHS had predicted that costs would fall as the service improved the health of the nation. The naivety of that prediction became all too obvious in a very short time and continued to vex successive governments. And so it was that in 1989 the Conservative Government published its White Paper Working for Patients, which attempted to drive quality improvement and greater economic control through the development of an ‘internal market’. Health care and medical treatment became commodities: purchased by local health authorities and GPs from hospitals restyled as independent trusts, all supposedly working together in the best interests of the new ‘consumer’. Unfortunately, capacity problems beset the best intentions of the reforms, and quality was soon overridden by financial constraint and cost containment. It rapidly became apparent that well-trained staff, good facilities and modern equipment do not automatically converge to create high standards of health care. Disaster struck, and serious failings in care standards hit the headlines through the early to mid-1990s. Where was the quality-assurance framework overseeing the work of trusts now in financial competition with each other?

In January 1995, a child called Joshua Loveday died at the Bristol Royal Infirmary after major heart surgery. This might have been viewed as a sad, but not very remarkable event were it not for the fact that Joshua died in a unit with a track record of unacceptably poor outcomes after such surgery. And, despite the fact that the Trust Senior Management was already aware of the outcome data and the need for significant service changes, Joshua’s surgery still went ahead—with tragic results.

The crisis in paediatric cardiac surgery in Bristol was the first of a series of high-profile cases that was to set the scene for a major change in Health Service philosophy. The Government White Paper The New NHS: Modern, Dependable (Department of Health 1997), closely followed by its sister paper A First Class Service (Department of Health 1998), continued the Conservative Administration’s theme of patient-centred care, but abolished the internal market in favour of a quality-driven model based on the principles of ‘clinical governance’. This is the framework through which NHS organisations must improve the quality of their services and safeguard high standards.

As Chief Medical Officer Liam Donaldson wrote in the Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health (Donaldson 1998:73)

A frequently aired concern of health professionals throughout the world is the extent to which financial issues dominate the health care agenda. If most of the time of the senior management of health care organisations is directed towards finance…how can a commitment towards quality be anything other than rhetoric?

And, speaking at an international symposium (Donaldson 1999), he highlighted the extent to which public expectations of the NHS also lie behind the changes. ‘Rising patient and public expectations are becoming a key stimulus to improving quality in the NHS. People—particularly those under 45 years—are less ready than in the past to accept a paternalistic style of service from the NHS.’

It’s about change

A philosophical and cultural sea change was clearly crucial, but was far from being the only development need. The NHS Plan (NHS Executive 2000) recognised under-investment and staffing shortfalls within the Health Service and set ambitious targets to remedy these. But while the promise to employ 7,500 more consultants, 2,000 more GPs, 20,000 more nurses and 6,500 more therapists is laudable, many questions remain unanswered: Where will extra staff come from? Who will train them? and How can resources keep pace with the extra investigations and procedures that a larger workforce would inevitably generate? Targets to cut junior doctors’ hours are seen as vital in ensuring that patients are not treated by doctors who are too tired to work safely, but how can this be reconciled with training needs—spending enough hours on the job to learn how to do it? What about the knock-on effect for consultants whose hours are less rigorously controlled?

As waiting-list targets multiply and public expectations escalate, alongside promises of increased choice about treatment dates and places, do we need more health-care centres and hospitals, or will this spread limited resources too thin? How can the convenience of local care be weighed up against the benefits of centralising services in a smaller number of large specialist centres? What do patients really want? and How can we get answers to all these questions?

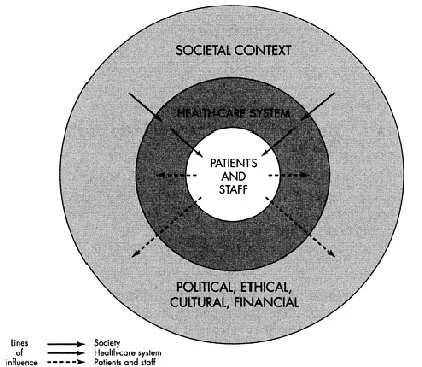

This book confronts real issues using a fictionalised account to illustrate generic topics. A central tenet of the book is that in almost every health-care episode there are three aspects to consider: the health-care system within which the action takes place; the societal context, be it political, cultural, financial or ethical; and the actions of the people at the front line, both patients and staff.

Each of the remaining chapters of the book is divided into two main parts. The first tells the Johnsons’ story, whilst the second analyses the issues and discusses how the most visible end point—the interaction between patients and staff—is influenced by the system and societal climate, which is the crucible within which that interaction takes place (see Figure 1.1). A closing section entitled ‘At the End of the Day’, uses the main fictional characters to explore outstanding points of tension, to highlight areas that remain particularly difficult to resolve, or simply to set out open questions. The book does not seek to prescribe neat, unrealistic cures for intractable health-care problems, but to open up the issues and discussion points. Learning points for both staff and patients are given throughout each chapter.

For those at the front line, whether staff or patients, part of the frustration when things go wrong is that they feel impotent to change or improve things. The health-care system seems like such a large and incomprehensible machine that no one individual can influence it. In reality, understanding the system and the broader context is important for a number of reasons:

Figure 1.1 Lines of influence in health care.

- First, because it allows those at the front line, both staff and patients, to make better sense of the situations in which they find themselves.

- Second, because it allows them not only to focus on the issues that they can influence most strongly, but also to understand that failings are not always the fault of the individuals most directly involved.

- Third, and perhaps most importantly, because local systems and processes are driven both externally and internally—externally by the b...