![]()

Part I

Priorities

Priorities are the very foundation upon which you will build your prosperous PEP mansion. Putting research as a high priority will generate the motivation and provide you with the time you will need to make all the rest happen. You will learn how to put fi rst things fi rst (Chapter 1), how to choose a topic you fi nd compelling and important (Chapter 2), and how to enhance the urgency of your research priority with goals (Chapter 3) and with deadlines (Chapter 4).

Figure 0.2 Principles of Enhanced Productivity

![]()

Main Chapter Points

•We trick ourselves into thinking research is our top priority when often it is not.

•We fear obstacles of the publishing process and must overcome these fears by courageously passing through the “fire swamp.”

•We fear other things will go by the wayside if we prioritize research, but we really can do it all.

•Set aside a specific time and place for daily writing.

•Tune out distractions.

•Set goals and make yourself accountable.

•Delight in deadlines.

•Choose a topic you find interesting and important.

Chapter Introduction

Evan knows how important publishing is; his career depends on publications! He feels like it is a priority for him; however, by the end of the week he rarely has done much of it. Where does all the time go? As a graduate student, there are many competing priorities and each of them seems much more urgent than research. He is accustomed to getting straight A's and doesn't want to lose his great track record. As a result, his coursework always comes first and he spends a great deal of time preparing for classes. After all, they always say you should spend three hours outside of class for every hour in class, and Evan does at least that. Next, he has a teaching assistantship, and this usually takes up far more than the 10 hours it is supposed to take. Once he's done all of these time-consuming tasks, there simply isn't much left for research. Plus, Evan would admit that he's still reeling from the sharp, harsh words from the reviewers in the first manuscript he submitted, which was rejected. He's been enjoying the thrill of getting straight A's in graduate school and likes the positive feedback he gets from his students, which makes him feel valued and successful. Evan realizes that part of the reason he struggles to get to the research is because he's reluctant to face the rejection and harsh criticism he encountered last time, especially when he gets so much positive feedback from these other, more urgent tasks.

The foundation for my productivity framework is priorities. If research and writing isn't the number one priority of your work day on most days, you will not likely achieve academic prosperity. I believe the primary reason for lack of publishing productivity is that it is not truly of top importance for many scholars. Most academics, if asked, would say research and publishing is a top priority for them, but the reality and hard data prove that, for most, this isn't actually the case. One study by Boice (1989) found professors thought they were working an average of 58 hours per week and researching an average of 31 hours each week. However, when they were required to report their time in 15 minute increments, reality showed a much different picture. The average professor was actually not working 58 hours but a mean of 29 hours! This shows that we often think we're working a lot more than we actually are. However, even more alarming was these professors estimated they were spending 30 hours a week on research, while their actual self-report data showed they spent only 90 minutes researching, and only 30 minutes writing!

Of course you may say, “Oh that may be the case with those academics, but I'm different.” However, I challenge you to track every 15-minute increment of your time in a time diary this upcoming week and see where you stand (see Appendix B). It may be a revelation to you to discover a discrepancy in where you think you are spending your time and what is actually happening with your time.

So what is going on? Why are many academics so misappropriating their time and energy? What is going on with their priorities? It's called self-deception. Many academics think they have their priorities straight and that they are putting enough emphasis on their research, but clearly the data suggest a different reality. So what can we do to change our priorities? I'm convinced that for research to actually become a top priority, we need to increase our perception of it being both important and urgent.

If you are reading this book, you are likely ahead of the game in realizing how important research and publishing are. Earlier in the book we discussed how publishing is the top item people look at when deciding who to hire, who to give tenure to, who to promote to full professor, who to give raises to, and so on. Though you're likely ahead of your peers in understanding the importance of research, we all have room for improvement.

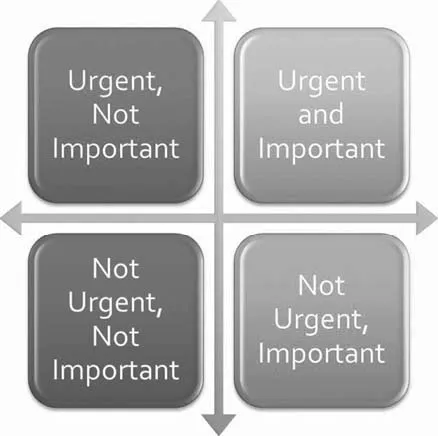

Even more notable than perceived importance of research, many scholars lack a sense of urgency toward research. Many other things that appear to be more pressing than research are constantly competing for your attention. Without enough urgency, no amount of perceived importance of research will compensate, and you won't ever reach your full productive potential. In the next

Figure 1.1 Urgency and Importance Matrix (Covey, 1989)

section, I will illustrate the interplay of importance and urgency by describing four quadrants in which we spend our time.

The High/Low Importance and Urgency Quadrants

“Life is composed of the urgent, the important, and the trivial. We exhaust ourselves on the urgent, seek rest in the trivial, and forget the important” (Webb, 1996–1999, as cited in Gray, 2010). Unfortunately, we spend a great deal of our time taking care of urgent matters that are of little importance. Covey (1989), author of bestseller The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, suggests there are four quadrants in which we spend our time:

Q1: Urgent, Important. This category of tasks takes up perhaps the most of an academic's time. After all, something like teaching occupies an important aspect of an academic's life, and the urgency of a class lecture that has not yet been fully prepared can make it difficult to get around to research. Part of the problem is the task at hand usually fills the amount of time you allot to it. Thus, the urgency of something like teaching often trumps research in time spent. This is also the case with citizenship endeavors and other things which are an important aspect of an academic's career and which also carry a great deal of urgency, therefore taking precedent over research time.

Q2: Important, Not Urgent, Unless your tenure clock is about to run cut, research tasks are important, but not typically urgent. Unfortunately, by the time the tenure clock is about to run out or the job market season is approaching, it's usually too late to get things published anyway, so the sudden urgency is in vain. Not only that, but unlike the immediate reward of teaching a good lecture, the rewards for research activities are extremely delayed. Thus, there are some strongly ingrained obstacles that prevent us from making research an urgent focus in our careers.

Q3: Urgent, Not Important. For researchers, this quadrant may include things like much of what you get with email. Many of the meetings academics sit through are not important, but they are certainly urgent.

Q4: Not Urgent, Not Important. This quadrant is comprised of tasks and distractions that aren't urgent or important. For researchers these may include surfing the Internet, checking Facebook, redecorating/cleaning your office, and the list goes on.

One objective of this chapter and ultimately of this book is to help you to put research in the first quadrant of urgent and important. You will only be able to fully maximize your productivity when this occurs.

Obstacles Preventing Research as a Priority

There are several obstacles that prevent us from making research a top priority. These include the fear of the many obstacles in the path to publishing, which I like to call the Fire Swamp, as well as the fear that other important things that are important will fall by the wayside as we prioritize research.

The Fire Swamp

Before reaping any rewards for research, one has to trudge through a great deal of perilous obstacles akin to those Wesley and Buttercup of the Princess Bride faced in the “Fire Swamp.” Many of you recall this classic film from the late 1980s in which Wesley captured his true love and had to face the Fire Swamp in order to evade potential captors. After dodging the flame spurts and rescuing Buttercup from the quicksand, Buttercup says, “Wesley, what about the R.O.U.S.'s?” to which Wesley replies, “Rodents of Unusual Size? I don't think they exist” (Princess Bride, 1987). He is then immediately attacked by this brutal beast. Likewise, after dodging the flame spurts of the Institutional Review Board, the quicksands of our failed experiments or data that do not cooperate, we are then often attacked by two or three rodents of unusual size: bloodthirsty reviewers. And even after fending off all these challenges in the Fire Swamp, there's still a good chance we'll make it out of this swamp only to be met by Prince Humperdinck (a heartless editor) and an entourage of armed soldiers, be forced...