![]()

1

INTRODUCTION: ORIENTATIONS

David Bell and Gill Valentine

The ‘sex lines’ listed in this advert (Plate 1.1) from London’s free gay paper Boyz mark one way in which we can read the space of a city as sexed and sexualised: as Paul Hallam (1993) discusses in The Book of Sodom, London’s streets are a powerful source of (homo)erotic imagery. In one sense, then, the landscapes of desire which this book seeks to address are the eroticised topographies—both real and imagined—in which sexual acts and identities are performed and consummated. This book might not be the best or only way to ‘Discover the truth about sex in the city’, but it should at least provide an introduction to ways in which the spaces of sex and the sexes of space are being mapped out across the contemporary social and cultural terrain.

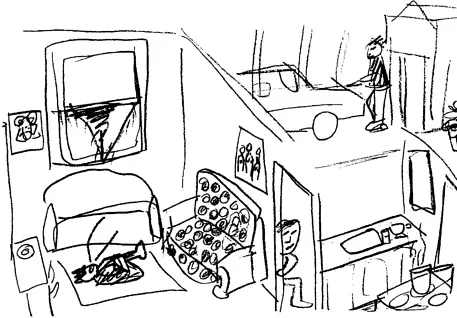

Of course, the London Boys telling and selling their tales over the phone will not have the same meaning for everyone. We need to think about locally sexualised spaces—what Stephen Pfohl (1993:192) calls ‘“vernacular” erotic geographies’—if we are going to avoid doing violence to the multitude of experiences and expressions of ‘sex’ in ‘space’. Consider the sharp contrast between the London Boys advert and the two drawings of ‘home’ also shown here (and, indeed, the sharp contrast between those two homes). These pictures (Plates 1.2, 1.3), from research by Lynda Johnston on New Zealand lesbians’ feelings about home (reported later in the book in a collaborative chapter with Gill Valentine), give us a very complex representation of the divided space of the (heterosexual) ‘family home’ and what might be called (in the rhetoric of the UK’s antigay Section 28 legislation) the lesbian and gay ‘pretended family’ home. Through subtle signifiers of heteronormativity (‘Dad’ washing the car, ‘Mum’ in the kitchen), the family home (Plate 1.2) is depicted as a place of walls, of separation, but also of surveillance and discipline (see also Colomina 1992 on the architecture of domestic space).

The ‘pretended family’ home, however, is a very different image (Plate 1.3): instead of the people being lost in the space of the home, their bodies almost constitute the home, with only a sketched roof above to offer shelter. But what is perhaps more remarkable about this drawing is the copresence of lesbians, gay men and a baby. Where once the rigours of sexual politics demanded separatism not only from heterosexist culture but also from the opposite sex, the ‘pretended family’ home now shatters those stereotypes, bringing lesbians and gay men together.

Plate 1.2 Portrait of a heterosexual ‘family home’

Source: Lynda Johnston

Very different places, then: the fetishised cityscape of London, and the intimate space of the home. It is our intention, in bringing together the authors in this collection, to present a set of equally different places and spaces, from the city to the desert island, from Jakarta to Amsterdam, from the red-light district to the merchant bank, from body to community, from local to global. And far from paying banal lipservice to these landscapes of desire, we hope to bring a range of theoretical and empirical perspectives, drawn not only from geography but also from much further afield, together to inform our thinking about the ways in which the spatial and the sexual constitute one another. To begin this process, we review work firstly by geographers and secondly from scholars beyond our discipline’s (porous) boundaries, before moving on to think about the project of researching and teaching sex, sexuality and sexual identity from within the academy—and from within the geographical academy in particular.

Plate 1.3 Portrait of a ‘pretended family’ home

Source: Lynda Johnston

PUTTING SEXUALITIES ON THE MAP

The women’s, gay and civil rights movements emerged in North America and Europe in the 1960s and 1970s on a wave of social and political upheaval. But despite a growing awareness amongst geographers in the following decade of the need to study the role of class, gender and ethnicity in shaping social, cultural and economic geographies, sexualities were largely left off the geographical map (Bell 1991).

Some of the first geographical works on homosexualities suggested that lesbians and gay men lead distinct lifestyles (defined to a lesser or greater extent by their sexuality and the reactions of others to that sexuality) which have a variety of spatial expressions creating distinct social, political and cultural landscapes. This research has focused almost exclusively on contemporary western societies and has largely followed attempts within urban sociology (e.g. Levine 1979a) to apply ideas from the work of the Chicago School of Human Ecologists (notably Park 1928 and Wirth 1928) to map ‘gay ghettos’. For example, Lyod and Rowntree (1978) studied the migration patterns of lesbians and gay men, arguing that they cluster in communities in specific parts of US cities for reasons of avoidance, defence, attack and preservation. Likewise, Harry (1974:246) argues that ‘by migration the relatively isolated gay may be able to replace the impersonality of small town life (for him [sic]) with the interpersonal warmth and cultural affinity of gay life in the big city’. Such explanations mirrored the arguments geographers used in the 1970s and early 1980s to account for concentrations of ethnic groups within cities (Boal 1976). This work has since been heavily criticised and largely rejected out of hand because of its ‘racist’ (and we might add heterosexist) assumptions (Jackson 1987). Other preliminary attempts to map gay regions and neighbourhoods were made by Barbara Weightman (1981) and by Hilary Winchester and Paul White (1988), who categorised lesbians alongside criminals, ethnic minorities and down-and-outs [sic] as neglected marginalised groups within the inner city.

Most of these studies relied on indirect information, such as directories of lesbian and gay venues and bars, to locate ‘gay communities’. In particular, the institutions and leisure services used by lesbians and gay men, especially the gay bar, were an easy target for researchers unable to or uninterested in getting their hands dirty talking to informants. Barbara Weightman (1980:9), for example, investigated the symbolism of gay bars— claiming that ‘gay bars incorporate and reflect certain characteristics of the gay community: secrecy and stigmatisation. They do not accommodate the eyes of outsiders, they have low imageability, and they can be truly known only from within’. This work follows in the footsteps of a number of ‘classic’ sociological studies of gay bars, for example, by Gagnon and Simon (1967), Achilles (1967) and Harry (1974), that painted a picture of promiscuity and sexual exploitation. These studies have subsequently been heavily criticised for their patronising, moralistic and ‘straight’ approach to lesbian and gay social and sexual relations. This approach is beginning to be redressed through more sex-positive work that is based on ethnographic research and interviews with lesbians and gay men, such as Jon Binnie’s (1992a, 1992b) studies of leather bars in the East End of London and in Amsterdam and Alison Murray’s chapter on lesbian sex workers.

The impact that gay communities have on the urban fabric at a neighbourhood level has been at the heart of much of the recent US work on sexualities (Castells 1983; Castells and Murphy 1982; Knopp 1987, 1990a, 1990b; Lauria and Knopp 1985; McNee 1984; Winters 1979; Wolf 1979). This literature has highlighted how gay men have taken over and gentrified areas such as West Hollywood in California, establishing not only gay housing areas and businesses but also, in the face of hostility and oppression, a power base where the ‘gay vote’ is significant (Knopp 1990a). In Chapter 10 Larry Knopp begins to try and establish a theoretical framework for this early work by examining the relationship between sexualities and aspects of urbanisation in contemporary western societies. This builds on some of his recent attempts to examine the role of sexuality within the spatial dynamics of capitalism (Knopp 1992).

British geographers have been less caught up in this concern with gay commercial and residential bases which perhaps reflects differences between the geographies of US and UK gay (and academic) communities. One exception is Jon Binnie’s work on Soho in London and Amsterdam. Part of his chapter examines the emergence of Old Compton Street in the West End of London as a gay commercial district—nicknamed ‘Queer Street’; and the development of Amsterdam, one of the gay capitals of Europe, as a location of international lesbian and gay tourism.

These gay commercial/neighbourhood bases in the US and Europe are predominantly populated by gay men (Castells 1983) and dominated by institutions of gay male culture. In this sense much of the 1980s work on sexuality has primarily produced geographies of gay men. Castells has claimed that the absence of similar territorially based lesbian communities reflects the fact that ‘women are poorer than gay men and have less choice in terms of work and location’ (1983:140). This is borne out by Maxine Wolfe’s (1992) assertion that there are fewer commercial spaces for lesbians than gay men because lesbians, like heterosexual women, rarely own their own businesses because of their lack of economic resources. Wolfe further argues that lesbian bars usually have a short life span, stating that

Many lesbian bars are not ‘places’ in the sense of a consistent physical location, which one could design or decorate permanently. Often they are ‘women’s nights’ at other bars. A few years ago in London, the ‘lesbian bars’ moved continually on different nights of the week (being held in the private, usually basement, party spaces in heterosexual pubs) to protect women from being beaten up.

Wolfe 1992:151

But Castells (1983) also goes one step further in his explanation for the lack of lesbian communities, suggesting that there are gender differences in the ways that men and women relate to space. He argues that men try to dominate and therefore achieve spatial superiority, whilst women have less territorial aspirations, attaching more importance to personal relationships and social networks.

Adler and Brenner (1992) have challenged Castells’ claims about lesbians. Their work in an anonymous US city suggests that lesbians do create spatially concentrated communities but that ‘the neighbourhood has a quasi-underground character; it is enfolded in a broader countercultural milieu and does not have its own public subculture and territory’ (Adler and Brenner 1992:31). Linda Peake’s (1993) study of lesbian neighbourhoods in Grand Rapids, Michigan and Gill Valentine’s (1995a) work on a town in the UK provide further evidence that lesbian spaces are there if you know what you are looking for. In both research areas there are ‘lesbian ghettos’ but they are ghettos by name and not by nature. There are no lesbian bars, stores or businesses in these neighbourhoods, neither are there countercultural institutions such as alternative bookstores and co-operative stores. The lesbians in these towns leave no trace of their sexualities on the landscape. Rather there are clusters of lesbian households amongst heterosexual homes, recognised only by those in the know. Both Peake and Valentine suggest that women learn about these areas and make contacts with people in the neighbourhoods through the ‘lesbian grapevine’—a process neatly captured by the title of Tamar Rothenberg’s chapter about a lesbian community in Park Slope, Brooklyn: ‘And she told two friends…’.

Rothenberg’s chapter also adopts a more critical approach to the use of the term ‘community’ than some of the earlier work on gay geographies. She points out how geographers have tended to use community and neighbourhood synonymously to refer to a geographically bounded area inhabited by close-knit networks of people, most of whom know each other or share common interests. More recently, geographers have begun to wake up to the problems of eliding these two terms and have begun to draw on Benedict Anderson’s (1983) concept of ‘community’ as an imagined but discursive reality. In his work on nations as ‘imagined communities’ Anderson suggests that nations are imagined ‘because the members of even the smallest nation will never know their fellow members, meet them, or even hear of them, yet in the minds of each they carry the image of communion’ (Anderson 1983:15). This concept is discussed in relation to lesbians and gay men (at local, national and international scales) not only in Rothen- berg’s chapter but also in the chapters by Jon Binnie and David Woodhead.

Despite the attention paid to visible gay communities like San Francisco, the reality is that most gay men and lesbians live and work not in these gay spaces but in the ‘straight’ world where they face prejudice, discrimination and queerbashing (Bell 1991). The hegemony of heterosexual social relations in everyday environments, from housing and workplaces to shopping centres and the street, is increasingly the subject of geographical research (Davis 1991, 1992; Valentine 1993a, 1993b) and has led Larry Knopp (forthcoming) to outline the need for lesbians’ and gay men’s oppressions to be recognised by geographers (e.g. Harvey 1992) who are taking up the cudgels again in the battle for social justice within the city.

Lesbians, like heterosexual women, are economically marginalised and are less likely than gay men to own their own homes (Anlin 1989; Egerton 1990; Wolf 1979). Housing, according to Egerton, is therefore the ‘single most chronic practical problem’ facing many lesbians (Egerton 1990:79). Whilst gay men often have more economic resources at their disposal, they also commonly encounter discrimination getting life insurance and endowment mortgages because of commercial paranoia about AIDS. Both groups have also been hit hard by recent housing legislation in the UK and the lack of provision of accommodation for single homeless young people.

Bell (1991) and Johnson (1992) have argued that most housing in contemporary western societies is ‘designed, built, financed and intended for nuclear families’ (Bell 1991:325) and that whilst lesbians and gay men can subvert conventional housing layouts to articulate their lifestyles there is no housing that is primarily designed for those who want, for example, to live in ‘non-conventional’ co-operative or collectively organised households. Notwithstanding this, Egerton (1990) and Ettorre (1978) have both documented lesbian-feminist housing experiments of squatting and communal living. Some of these issues are addressed in Johnston and Valentine’s chapter about the performance and surveillance of lesbian identities in the home.

Feminists in geography and elsewhere (e.g. Cockburn 1983; L.Johnson 1994) have been flagging the ritualised performance of gender identities in the workplace and the ways that the sexual division of labour is inscribed on workers’ bodies for the last decade. More recently research has drawn attention to the fact that such performances of masculinity and femininity make sense only within a heterosexual matrix. The disciplinary practices that regulate the performance of heterosexuality within ‘City’ workplace environments are the subject of Linda McDowell’s chapter. Sally Munt also examines another aspect of the way different spaces are (hetero)sexed when she compares the experience of being a lesbian in Brighton, the gay capital of the South, with living in Nottingham, a place she characterises as possessing a ‘rugged romantic masculinity’.

But as Jerry Lee Kramer points out in his chapter on lesbian and gay lives in rural North Dakota, most of the geographical work on sexual identities and the sexuality of space remains firmly located in the urban (reflecting the discipline’s general obsession with the city). Indeed social constructionist arguments about the development of gay identity suggest that this is predicated upon the opportunities offered by city life— anonymity and heterogeneity as well as sheer population size. Even the suburbs and small towns have been passed over in the rush to study the glamorous and sexy city. One of the few exceptions is the now rather outdated work of Fredrick Lynch (1987). He documented some of the problems gay men have developing social and sexual relations with other men in middle-class suburban environments. This problem is felt...