- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Recent years have witnessed radical changes in British economic policy. However, the recession of the early nineties has cast doubts about whether these were successful. The much heralded economic miracle is now much tarnished. This book offers a timely and comprehensive non-technical throughout it analyses the basis of policy making as well as discussing its impact on economic performance.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

FROM KEYNESIAN DEMAND MANAGEMENT TO THATCHERISM

Nigel M.Healey

INTRODUCTION

In November 1990, Margaret Thatcher resigned as Prime Minister, bringing to an end one of the most remarkable political careers of modern times. During her eleven years in office, her government transformed the face of British macroeconomic policy, shattering the ‘postwar consensus’ that had grown up since 1945. Prior to 1979, successive governments had sought to maintain aggregate demand at a level sufficient to achieve ‘full employment’. In other words, demand-management policy had been directed towards ‘real’ macroeconomic objectives for output and employment. In contrast, ‘supply-side’ policies (i.e. policies designed to influence private sector decisions to produce goods and services) had primarily taken the form of rules and regulations, notably controls that limited the size of wage and price increases which companies were permitted to make.

Mrs Thatcher’s government was elected on the basis of a programme which was diametrically opposed to the economic philosophy of the postwar consensus between the two major political parties. The incoming administration rejected the notion that demand management could be systematically used to promote high levels of output and employment, arguing that such a strategy was a recipe for ever-accelerating inflation. The new government advanced the (then) radical proposition that fiscal and monetary policies should be directed towards re-establishing price stability, regardless of the short-run costs in terms of falling output and higher unemployment. Mrs Thatcher’s ministers also claimed that postwar supply-side policies had been fundamentally misconceived, suffocating the ‘wealth-creating’ market economy with bureaucratic ‘red-tape’. Turning conventional wisdom on its head, the Thatcher government contended that the only way of revitalising the real economy, thereby returning to the high rate of economic growth and low rates of unemployment enjoyed in the 1950s and 1960s, was to sweep away the paraphernalia of state interventionism with a revolutionary programme of privatisation, deregulation and market liberalisation.

Although macroeconomic policy has evolved considerably since 1979, the early Thatcher years have left a lasting impression on subsequent developments. The once-rigid ‘monetary targets’, which were intended to lock demand-management policy on to a non-inflationary path, have given way to membership of the European Monetary System (EMS). By joining the EMS as a full member in October 1990, Britain implicitly agreed to tie its domestic monetary policy stance to the stance pursued by the European Community’s lowest-inflation member, Germany (Artis, 1991). Zero inflation has been replaced by ‘German inflation’ as the target of demand-management policy. But the use of demand-management policy to achieve ‘nominal’ objectives for the rate of inflation—rather than ‘real’ objectives for output and employment— has endured and (given Britain’s commitment to the EMS) will continue to shape macroeconomic policy for the rest of the decade.

Supply-side policy, which has also been in a constant state of flux since 1979, nevertheless retains almost no point of tangency with the past. The intellectual baggage of the postwar consensus, which included nationalisation, state planning, and prices and incomes controls, is now disowned by all the mainstream political parties. Recent events in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, which have been interpreted across the political spectrum as evidence of the failure of central planning to replace the role of the ‘invisible hand’ (i.e. the price signals generated by a free market economy), have hastened the retreat from state interventionism. While concern about the environment has raised fears about the costs of uncontrolled economic growth, contemporary proposals to create a ‘greener’ society are almost universally predicated on assumptions of private ownership of capital and minimalist government controls.

The effects of this dramatic shift in the objectives and conduct of economic policy have not unsurprisingly provoked enormous controversy (e.g. Green, 1989). Many commentators have claimed that the economic benefits that apparently flowed from ‘Thatcherism’ have been illusory and that, once the distortions injected into the statistical data by a deep recession between 1979–82 and an unchecked boom between 1982–9 are stripped out, Britain’s underlying performance is either little changed or actually worse than before. In contrast, supporters of the post-1979 policies maintain that Britain has undergone an ‘economic renaissance’ which, once the present recession has run its course, will ensure permanently higher growth rates and lower unemployment levels. Others concede that national living standards have increased at a faster rate since 1979 but, harking back to a ‘gentler, more caring’ era, fear that the social costs in terms of greater social and regional inequalities have proved unacceptably high.

This book explores the development of economic policy in Britain since 1979 and considers many of these important debates (see also Campbell et al., 1989). Part I (Chapters 2 to 7) offers different interpretations of the macroeconomic impact of recent policy, in terms of its effects on inflation, unemployment, economic growth and the balance of payments. Part II (Chapters 8 to 13) concentrates on a range of contemporary microeconomic issues—for example, the effects of privatisation, the changing distribution of income and the ‘North-South’ divide. The role of the present chapter is to provide a theoretical ‘lens’ through which subsequent chapters can be viewed. It examines the Keynesian theories that underpinned the era of demand management between 1945 and 1979 and, within the context of the aggregate supply and demand framework, contrasts this body of thought with the new classical macroeconomics that has come to dominate British policymaking since 1979-In particular, it introduces readers to the major theoretical innovations and controversies of recent years—‘rule’ versus ‘discretion’, ‘monetary targets’, ‘credibility’ and ‘supply-side economies’—and prepares the ground for the chapters that follow.

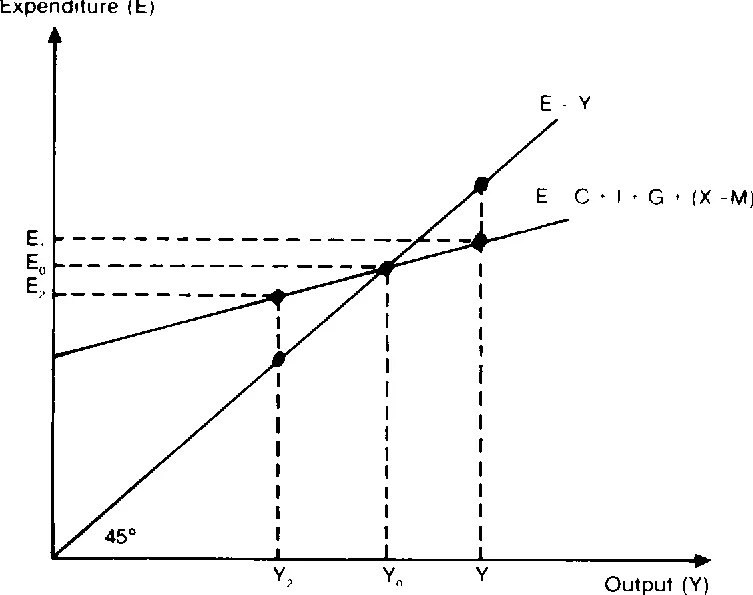

THE KEYNESIAN 45-DEGREE LINE DIAGRAM

The approach to macroeconomic policy that characterised the period 1945–79 is captured by the familiar, ‘Keynesian’ 45-degree line diagram (see Figure 1.1). The 45-degree line shows points at which there is equilibrium in the ‘goods market’, that is, where planned expenditure (E) is equal to output (Y). Unless planned expenditure (E)—which comprises the sum of household consumption (C), corporate investment (I), government spending (G) and net exports (X-M)—is equal to output (Y), there will be disequilibrium in the sense that the business sector will find its inventories (i.e. stocks of unsold goods) rising or falling in an unintended fashion. Under such circumstances, firms will tend to adjust current output in the light of actual sales in the previous time period. But because the process of producing output generates an equivalent income for the household sector—in the form of profits, interest, rent and wages—as firms change output, households will be forced to revise their consumption plans, so that the business sector again finds itself with a level of output inappropriate to the level of planned expenditure.

Figure 1.1 Equilibrium in the 45-degree line diagram

We can use the 45-degree line diagram to illustrate this interaction between firms adjusting output and households altering consumption. The expenditure schedule (E=C+I+G+(X-M)) in Figure 1.1 shows how planned expenditure (E) varies with current output or income (Y). Although investment (I), government spending (G) and exports (X) are conventionally assumed to be exogenous (i.e. determined by forces outside the model), because consumption (C) and imports (M) are influenced by current income, total expenditure varies with income. Specifically, the higher the level of income, the higher the level of consumption and imports. Since the increase in consumption (which adds to expenditure) must necessarily be at least as large as the increase in imports (which reduces expenditure on domestic output), the former effect normally far outweighs the latter and the expenditure function is upward-sloping; that is, total expenditure rises with income.

By superimposing the expenditure schedule on the 45-degree line, we can see that there is only one point at which planned expenditure and output are equal (E0, Y0). Above Y0 at Y1, planned expenditure (E1) would be lower than output. Inventories would rise and firms would cut back output (and income); expenditure would fall (but by less than the reduction in income) and the economy would gradually converge on E0, Y0. The same sequence of events would take place in reverse if the economy were initially at a level of income below Y0 at Y2, planned expenditure (E2) would be higher than output, inventories would fall, and the business sector would step up production, adding to income and expenditure and driving the economy back to E0, Y0.

THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF THE 45-DEGREE

LINE DIAGRAM

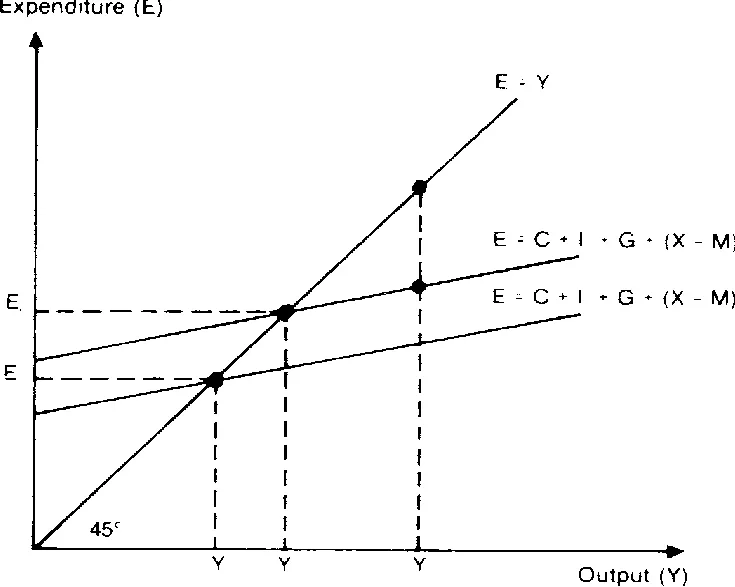

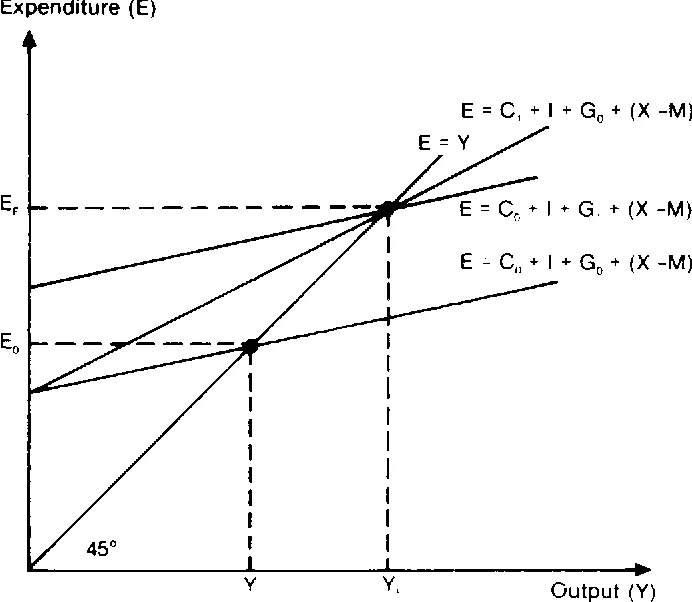

Several major conclusions can be drawn from this simple model. First, there is no reason why the equilibrium level of income (or output) on which the economy converges should be consistent with the government’s policy objectives. All other things equal, output and employment are closely related. Suppose that in Figure 1.2, YF is the level of output consistent with ‘full employment’ in the labour market (NB the relationship between output and employment is explored more fully below). With the economy in equilibrium at E0, Y0, there is clearly considerable unemployment. Second, the model suggests that a key reason for fluctuations in the levels of output and employment may be random shifts in the exogenous components of planned expenditure. For example, investment is greatly influenced by the state of business confidence, which is notoriously unstable over time. Suppose that a rise in interest rates (the cost of borrowing) triggers a collapse in business confidence. This could cause a sharp fall in investment, shifting the expenditure schedule in Figure 1.2 downwards from E=C+I0+G+(X-M) to E=C+I1+G+(X-M), pushing the equilibrium level of output further away (from YF to Y1. The same downward shift in the expenditure schedule could result, all other things equal, from a slump in exports, perhaps following a recession in foreign markets. Finally, because (i) the economy can lodge at equilibrium levels of output below full employment and (ii) investment and (possibly) exports may change in a way that gives rise to undesirable fluctuations in output and employment, the 45-degree line model suggests that the government should take responsibility for managing the economy. The government can alter its spending plans to raise or lower the expenditure schedule, propelling the equilibrium level of income to YF and thereby avoiding prolonged periods of high unemployment (see Figure 1.3). And it can ‘fine-tune’ its own spending plans to neutralise the random changes in investment and exports which would otherwise tend to drive the economy away from full employment. Note that the government could achieve the same ‘stabilisation’ of income through the use of tax policy. This would work by changing the share of income pre-empted by the government in the form of taxes, causing households to increase or reduce the proportion of any change in income that they spend buying firms’ output (‘the marginal propensity to consume’). A tax cut would increase the marginal propensity to consume, making the expenditure schedule steeper so that it intersected the 45-degree line at YF rather than Y0 (see Figure 1.3); and vice versa, in the case of a tax increase.

Figure 1.2 Investment and unemployment

Figure 1.3 Fine-tuning for full employment

THE POSTWAR CONSENSUS

In the 1950s and 1960s, successive governments took the message of the 45-degree line model to heart. Reflecting the growing political influence of ‘Keynesian’ ideas, the wartime coalition government published the famous ‘White Paper on Employment’ in 1944, committing future peacetime governments to take responsibility for stabilising income at its full-employment level. Over the following thirty-five years, ‘discretionary’ fiscal policy (i.e. frequent changes in government spending and taxes) became the main policy tool for keeping the economy at a permanently high level of employment. During this period, monetary policy played an essentially supporting role. While it was recognised that corporate investment could be influenced by changing interest rates (so that expenditure could be boosted by a cut in interest rates rather than government spending increases or tax reductions), it was generally reckoned that the final effects on income were weak and unpredictable when compared with the impact of fiscal measures.

The 1950s and 1960s were the high point of the so-called ‘postwar consensus’ betwee...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- ILLUSTRATIONS

- CONTRIBUTORS

- PREFACE

- ABBREVIATIONS

- 1: FROM KEYNESIAN DEMAND MANAGEMENT TO THATCHERISM

- PART I: COMPETING PERSPECTIVES ON THE MACROECONOMY

- PART II: CONTEMPORARY MICROECONOMIC ISSUES

- REFERENCES

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Britain's Economic Miracle by Nigel Healey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.