- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Arising from a research project funded by Danish International Development Assistance, Management and Change in Africa includes results of management surveys across 15 sub-Saharan countries and of organizational surveys taken across a range of sectors in South Africa, Kenya, Nigeria and Cameroon. It combines methodology, theory and case examples to explore thoroughly the influences on management in Africa and attempts to push the boundaries of cross-cultural theory. In doing so, it explores how much can be learned from studying both the successes and failures of African management towards realizing the potential of an African Renaissance and what the global community may learn from Africa.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Management and Change in Africa by Terence Jackson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Rethinking management in Africa

Chapter 1

Management systems in Africa

The cross-cultural imperative*

The foreigner interested in designing, implementing and evaluating effective management development programmes must read widely in order to gain an appreciation of this diverse and complex continent, its peoples and social organizations, and the context within which organization and management takes place.

(Kiggundu, 1991: 32–3)

For many centuries, Africa remained a mystery. It attracted the curiosity of explorers while fascinating and captivating empire-builders by its vast wealth. The length and breadth of Africa were explored, discovered, conquered and colonized. Its people were denigrated as ‘backward and inferior’.

(Ayittey, 1991: xxiii)

The need to understand and appreciate the diversity and complexity of sub-Saharan Africa has been largely hampered by an apparent continuation of a pejorative view of Africa, Africans and the contributions that can be made not only to the development of their own continent, but especially to other continents: not least in the area of management. It is rare to find a chapter on African management and its contributions to global managing in textbooks on international management, as we discussed in the Introduction. Indeed, the current literature on management in ‘developing’ countries generally (e.g. Jaeger and Kanungo, 1990) and management in Africa specifically (e.g. Blunt and Jones, 1992) presents a picture which sees management in these countries as fatalistic, resistant to change, reactive, short-termist, authoritarian, risk reducing, context dependent, and basing decisions on relationship criteria, rather than universalistic criteria. Apart from the pejorative nature of this description and contrast with ‘developed’ countries, there is the danger that the objective of development is to make the ‘developing’ world more like the ‘developed’ world, and that this should be reflected in the direction of organizational change and the way people are managed.

It is unfortunate that this perspective paints a rather negative picture of management in Africa, and one within the ‘developing–developed’ world paradigm that is not just pejorative, but actually hampers constructive research into the nature of management of people and change in Africa. Yet it is likely that the perceived ‘African’ approach reflects a colonial legacy rather than an indigenous approach to organizing. Indeed, the dynamics of management of organizations in Africa arise fundamentally from the interaction of African countries with foreign powers and corporations, as well as through exposure to foreign management education. In addition, managers in Africa increasingly have to manage the cross-border dynamics as regional cooperation increases (Mulat, 1998), and have had to manage the internal dynamics of inter-ethnic cross-cultural difference and diversity since the ‘scramble for Africa’ ensured national boundaries which conformed to the claims of European powers rather than existing African ethnic divisions.

If anything, ‘African Management’ is cross-cultural management. One of our main objectives is trying to understand the complex cross-cultural dynamics in African countries. The aim of managers and management developers should be to ensure the more effective management of these dynamics, by first understanding them, and then addressing the need to develop effective cross-cultural management and management teams.

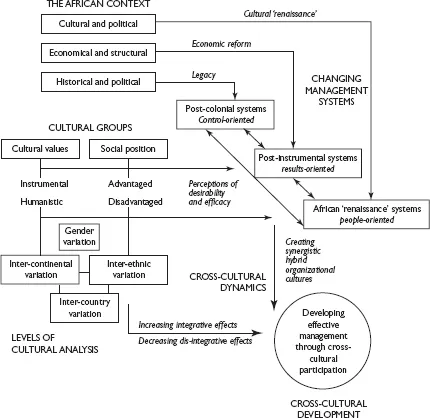

This chapter therefore attempts to reframe our understanding of the management of people, organizations and change in sub-Saharan African countries, by employing a paradigm that reflects the different perceptions of the value of human beings in organizations (Jackson, 1999), and by explore a model of cross-cultural dynamics in Africa which incorporates at least some of the complex elements which may be important to our understanding (Figure 1.1). We then look in more detail at the cross-cultural processes and dynamics in Chapter 2.

The African context

The context can best be understood as an historical dynamic that has created a number of paradoxes in Africa. The paradoxes can only be really understood by first considering the inter-continent level of cultural analysis. The main paradox is between the nature of organizations, and the need to develop human capacity. Many African economies are going through a stage of transition from large and often overly staffed public corporations, to enterprises which are more publicly accountable and private enterprises which have to compete globally and be profitable (Barratt-Brown, 1995; Ibru, 1997) (this aspect is shown as ‘Economic Reform’ in Figure 1.1). At the same time there is an overriding need to develop people (Bazemore and Thai, 1995; Kamoche, 1997; Kifle, 1998), and to do this predominantly within work organizations (cf. Anyanwu, 1998). Yet organizations that can take this development role are divesting themselves of people.

A legacy of under-skilling largely through a concentration on export-led primary production and low development of consumer economies (Barratt-Brown, 1995; Adedeji, 1999) now hampers human capacity building particularly in the service sector. Also, the current need to develop relevance, flexibility, responsiveness and accountability in the public sector is hampered by a legacy of administration that was tacked onto African societies with a standardization of functions and low transferability of skills (Picard and Garrity, 1995; Carlsson, 1998) (‘Legacy’ in Figure 1.1). More recently an imposition of economic structural adjustment programmes which have reduced government spending, removed subsidies, deregulated goods, money and labour markets, and decontrolled prices to respond to market forces and liberalization of trade (Mbaku, 1998; Wohlgemuth et al., 1998) has militated against protecting and developing indigenous organizations through long-term government and private investment in organizations to develop human capacity (‘Economic Reform’ in Figure 1.1). The accompanying trend to downsize organizations has also militated against training and developing people in these organizations.

Figure 1.1 A model of cross-cultural dynamics in sub-Saharan Africa.

The paradox (and conflicts in policies and practices) between historical legacy and future requirements; between the need to downsize organizations through economic reform, to make them ‘meaner and leaner’ and globally competitive on the one hand and the future requirement to skill, re-skill and develop people in work organizations up to managerial levels, may be understood through a conceptualization of an antithesis between the cultural need in Africa to recognize people as having a value in their own right and as part of a social community, which may be in direct contradiction to a predominant Western view in organization and management theory which sees people as a means to an end within the organization (Jackson, 1999). This perception of the direction and nature of the value that is placed on people in organizations, or locus of human value, which is shown as ‘Humanistic’ and ‘Instrumental’ cultural values in Figure 1.1, may be central to understanding at least one level of cross-cultural interaction within organizations in Africa. It may also be central to understanding many of the difficulties of managing people in organizations in Africa. It is to this level of analysis that we must turn to further understand the ‘changing management systems’ depicted in Figure 1.1.

Levels of cultural analysis

The inter-continental cultural level is fundamental to a number of theories such as the ‘disconnect’ thesis (Dia, 1996; Carlsson, 1998). At the naïve level of theorizing this may be seen as a difference between ‘developing’ and ‘developed’ countries (Jaeger and Kanungo, 1990; Blunt and Jones, 1992). A number of studies have incorporated Hofstede’s (1980a) cultural dimensions to explain some of the differences between African and ‘Western’ countries (Kanungo and Jaeger, 1990; Dia, 1996; Iguisi, 1997). The shortcomings of these approaches will be examined below. Recent cross-cultural studies have incorporated more sophisticated value constructs such as those of Schwartz (1994) (e.g. Munene et al., 2000), or have tried to develop value constructs that incorporate ‘African’ values (Noorderhaven and Tidjani, 2001). An alternative or complementary approach is offered here which develops a theory of ‘locus of human value’ and helps in an understanding of management and organization systems operating in Africa that focuses on inter-continental cultural interactions: principally African cultures with Western countries.

Less developed is work on other levels of cultural analysis that often requires more sophisticated concepts and research tools. Hence understanding cross-cultural interaction at the regional and cross-national levels, which is becoming more important with the establishing of regional trading agreements (Mulat, 1998) and more inter-country interaction, is at very early stages. Some of the studies mentioned above in connection with inter-continent comparisons are suggesting differences among African countries (particularly Noorderhaven and Tidjani, 2001). However, the lack of sophistication of quantitative measurement instruments, and the lack of qualitative comparisons, has hampered understanding at this level. As a result of a country’s unique interaction with a former colonial power, inter-continental interactions are likely to be bound up with inter-country differences and similarities.

Inter-ethnic cultural analysis has remained largely within the domain of social/cultural anthropology, and has been investigated or applied rarely to management and organization theory. This level of analysis is important for understanding potential and actual conflict in the workplace, and in addressing resulting issues of cross-cultural management in African countries. The inter-continental level of analysis is primarily focused upon here, as this has a direct bearing on a discussion of locus of human value, and on the changing management systems depicted in Figure 1.1.

Inter-continental cultural level of interaction

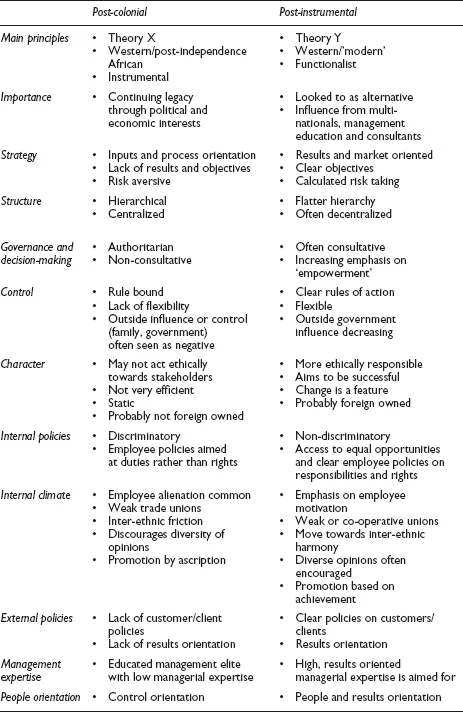

Cross-cultural management theory has been criticized for its lack of theory that connects cultural values to management and work practices, particularly at the behavioural level (Cray and Mallory, 1998). The focus of interest in this book is at the level of management and organization systems, their cultural derivatives, how they are manifested particularly in the management of people, and how they operate in Africa. This focus has the most relevance to practising management in understanding the influence of cultural factors, and for management and organizational development practices. Although at the theoretical level these systems can only be constructed as ideal types, they can form the basis for cross-cultural investigation, as well as informing management practices in Africa which often have to reconcile these various systems. This approach is particularly useful in attempting to overcome and integrate some of the complexities of the effects of different cultures on African societies generally and management and organizational practices in particular. These systems are described as ‘post-colonial’, ‘post-instrumental’ and ‘African renaissance’. Table 1.1 also includes a comparison of the three systems with that of a fourth ideal type: an East Asian/Japanese system. Table 1.2 postulates how these management systems may be manifested in different sets of management attributes.

Post-colonial management systems

Description of management in Africa has largely been informed by the developed–developing world dichotomy as was noted above, and exemplified in the work of Blunt and Jones (1992), one of the most thorough descriptions, and that of Jaeger and Kanungo (1990) of management in ‘developing’ countries in general. This is particularly in the distinction made between ‘Western’ management styles (teamwork, empowerment, etc.) and ‘African’ styles (centralized, bureaucratic, authoritarian, etc.) (Blunt and Jones, 1997).

ORGANIZATIONAL SYSTEMS

However, systems of management identified in the literature as ‘African’ (Blunt and Jones, 1992; 1997) or as ‘developing’ (Jaeger and Kanungo, 1990) are mostly representative of a post-colonial heritage, reflecting a theory X style of management (from McGregor) which generally mistrusts human nature with a need to impose controls on workers, allowing little worker initiative, and rewarding a narrow set of skills simply by financial means. This system is identified in the literature as being ‘tacked on’ to African society originally by the colonial power (Dia, 1996; Carlsson, 1998), and being perpetuated after independence, perhaps as a result of vested political and economic interest, or purely because this was the way managers in the colonial era were trained (Table 1.1).

In terms of strategies there is an emphasis on inputs (particularly in the public sectors such as increasing expenditure on health, education and housing after independence) to the exclusion of outputs such as quantity, quality, service and client satisfaction (Blunt and Jones, 1992), or the supply side rather than the demand side of capacity-building (Dia, 1996). Best use is not being made of inputs or the supply to organizations (generated through improvement in education and training) through capacity utilization within organizations. Table 1.1 therefore indicates a lack of results and objectives orientation, and a possible associated risk aversion. Kiggundu (1989) adds that there is typically a lack of a clear mission statement or sense of direction.

Table 1.1 Comparison of different organizational management systems in Africa

| African renaissance | East Asian/Japanese |

• Humanistic | • Humanistic |

• Ubuntu | • Corporate collectivism |

• Community collectivism | |

• Some elements may prevail in indigenous organizations | • Developing importance through East Asian investment |

• Of growing interest internationally | • May be seen as alternative |

• Stakeholder orientation | • Market and results orientation |

• Clear objectives | |

• Low risk taking | |

• Flatter hierarchy | • Hierarchical and conformity |

• Decentralized and closer to stakeholders | |

• Participative, consensus seeking (indaba) | • Consultative but authority from top |

• Benign rules of action | • Consensus and harmony above formal rules |

• Outside influence (government, family) may be seen as more benign | • May have a lack of flexibility |

• Stakeholder interest may be more important than ‘ethics’ | • Harmony and face may be more important than ethics |

• Success related to development and well being of its people | • Efficiency • May be slow to change |

• Indigenous | |

• Stake-holder interests | • Can be discriminatory (towards women) |

• Access to equal opportunities | • Employee relations may be more implicit |

• Motivation through particip... |

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Preface

- Introduction: Africa – why bother?

- Part I Rethinking management in Africa

- Part II Managing competencies and capacities

- Part III Learning from countries and cases

- References

- Index