- 96 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Explaining in the Primary School

About this book

This book is one of a set of eight innovative yet practical resource books for teachers, focussing on the classroom and covering vital skills for primary and secondary teachers. The books are strongly influenced by the findings of numerous research projects during which hundreds of teachers were observed at work. The first editions of the series were best sellers, and these revised second editions will be equally welcomed by teachers eager to improve their teaching skills. Ted Wragg and George Brown show what explanation is and what it aims to do. The book explores the various strategies open to teachers and, through a combination of activities and discussion points, helps them to build up a repertoire of ideas, approaches and techniques which are suitable for various situations, as well as evaluate the effectiveness of their explanations in the classroom. Along the way it covers such issues as:

*the use of an appropriate language register

*the place of analogies *building on children's questions

*coping strategies for effective explanation

The ability to explain something clearly is a skill which effective teachers use every day. Explanation is the foundation on which the success or failure of a great deal of other forms of teaching can rest. Well done, it saves time and provides motivation. Badly done, it produces uncertainty, or even puts children off their studies.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Unit 1 What is explaining?

A brilliant explanation of a concept or process can change someone’s life. A teacher we once interviewed in a research project described vividly how his own former teacher, explaining the symbiotic relationship between ants and aphids, had awakened an interest in and curiosity about science that had led to him becoming a science graduate and wanting to teach the subject himself. The effects of good explaining can be significant and far-reaching.

Explaining is not a single type of activity. The words ‘explain’ and ‘explanation’ can be used in different ways. Consider these four statements:

‘Why are you two messing about when I’ve already told you once not to? I want an explanation.’

‘Miss, can you explain how to do this sum?’

‘You’ve just been told by the garage that you’ll have to buy a new battery? That explains why your car wouldn’t start.’

‘Can you give me an explanation of why water freezes in winter?’

In the first statement, the quest for an ‘explanation’ is probably a prelude to a reprimand. The children are not really being asked for an account of personality factors, genetic endowment or environmental influences on their personal and social development. Just imagine the teacher’s reaction if the child’s ‘explanation’ began, ‘According to experts on ethnology, rough-and-tumble play is a well-documented feature in the behaviour of young primates.’ In this context, the request for an ‘explanation’ is expected to produce a feeble justification or an apology. In the second example, the response may be a brief clarification and reminder of a specific technique already learned, such as how to solve a maths problem using fractions, or it may involve a fundamental explanation of what a particular mathematical transaction involves, to a pupil who has no understanding whatsoever of it. The third example, on the other hand, is the identification of a simple relationship between cause and effect: the car would not start owing to a dying battery. In the fourth case, the ‘explanation’ offered by a pupil could vary enormously in complexity. A satisfactory answer from a 6-year-old might be that water freezes ‘because it’s very cold in winter’. A 12-year-old might be expected to say, ‘because the temperature has dropped below freezing point, which is 0 degrees centigrade’. A Nobel prize-winner might write a treatise on the structure of matter at differing temperatures, which could be incomprehensible to the lay audience.

We shall take as our operational definition, therefore, the statement: ‘Explaining is giving understanding to another.’

This definition takes for granted that there are numerous contexts in which this may occur, many forms that explanations may take, and varying degrees of, and criteria for, success. Cruickshank and Metcalf (1994) put forward three types of explanations, dealing with concepts, procedures, or rules. We take a broader view, believing that an explanation can help someone understand, among other matters:

concepts including those which are new or familiar to the learner, like ‘density’ or ‘prejudice’;

cause and effect that rain is produced by the cooling of air, that a flat battery causes car-starting problems;

procedures classroom rules, homework requirements, how to convert a fraction to a decimal, how to ensure safety during gymnastics;

purposes and objectives why children are studying the topic, what they can expect to have learned at the conclusion of a particular task;

relationships between people, things or events: why footballers and pop-stars are both called (sometimes mistakenly) ‘entertainers’; why flies and bees are insects, but spiders are not; what are the common features of festivals, like Christmas, Diwali, Passover;

processes how machines work, how animals or people behave.

There are numerous other kinds of explanation, and also there are variations of the categories given above. For example, explaining consequences can be similar, but is not necessarily identical to cause and effect explanation. The consequence of putting your hand into scalding water will be intense pain and a visit to the hospital. A cause and effect explanation might concentrate on how intense heat destroys tissue and what causes pain, but an explanation of consequences might look at such matters as the foolishness of an action, its effect on others as well as the victim, and the cost in time and money of treating self-imposed injury. Furthermore, some explanations can cover more than one category. Explaining to a class what the Roman wall is, could involve concepts (‘aggression’, ‘defence’), cause and effect (what led to the wall being built), processes and procedures (how the wall was built, on whose authority) and purposes (to keep out the enemy).

Activity 1

A group of student or experienced teachers are working together to look at how explanations can be improved. Let a member of the group choose a hobby or interest he or she has. Just one key aspect of this interest should then be explained to the rest, taking no more than four or five minutes. There are countless possibilities, such as: what I like about chess; my favourite twentieth-century building; a simple recipe; getting rid of litter; how to lose weight; an effective advert; why lifeboats don’t sink; the best (or worst) thing about being a parent, or having an older brother/sister; home insulation or the play/piece of music/poem/ painting that moved me most.

Analyse the nature of the explanation, using, if possible, an audio- or video-tape of it. What were the key concepts? What types of explanation were involved? How effective an explanation was it, and why?

Audience

Those who receive the explanation must be an important consideration, so consider what differences and similarities there might have been if the explanation had been directed to:

- an 8-year-old with slight learning difficulties;

- a bright 11-year-old;

- an intelligent Martian.

Let the person have a second attempt at explaining a different topic, or the same one, in the light of feedback.

MAIN FEATURES OF EXPLANATIONS

Keys

Activity 1 should demonstrate a number of fundamental features of effective explaining. First of all there are several keys which help to unlock understanding. A key may be a central principle or a generalisation. It may contain an example, or an analogy. For instance, if someone were describing a recipe for making an omelette, then the notion of heat would be central. If too little heat is applied eggs will not set, if too much, then the eggs will burn and the omelette will resemble a cork tablemat.

It is not too difficult to see other keys to understanding how to cook an omelette. The question of taste will occur, and thus the addition of flavourings like salt and pepper, or fillings like cheese or mushroom. Texture is also important, hence the need to beat the eggs so that yolk and white mix evenly and to introduce air so the omelette will be light. The great chef Escoffier used to put little pieces of butter into the egg mixture which melted during cooking and affected both taste and texture, so this might be a concrete example used to illustrate one or more of the central notions or keys in the explanation. Where omelettes are concerned, the difference between a good and a bad explanation could be the difference between an Escoffier masterpiece and a poultice. Introduce a key concept like health and the need to avoid too much salt and too many dairy products, and to cook eggs to a certain temperature to prevent salmonella, and you may not have your omelette at all!

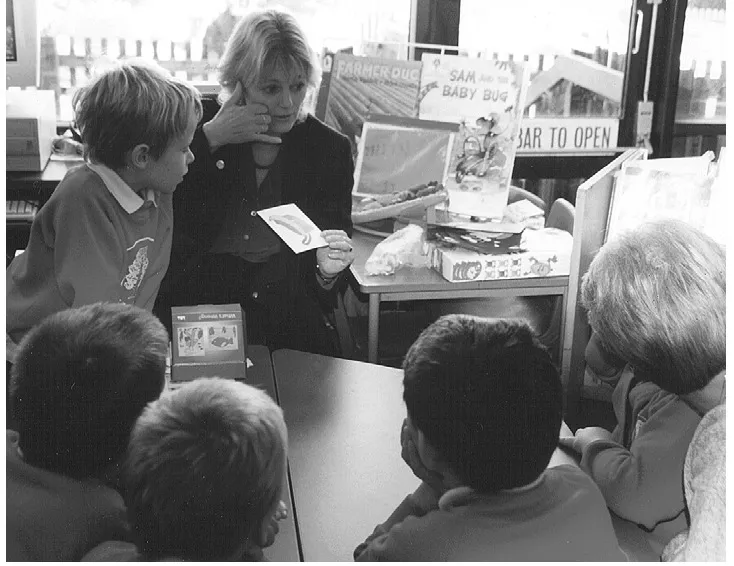

Voice and gesture can amplify explanations

Voice and gesture can amplify explanations

There is more to an explanation, however, than a bunch of keys. The voice of the explainer is important. The same text read by someone with a pleasant, well-modulated voice and another person with a flat, tedious delivery, will sound quite different. The correct use of voice involves light and shade, knowing when to slow down or accelerate, which words or phrases to emphasise, when to pause and how to ‘read’ the audience so that the appropriate tone of voice is used: hushed for something serious, lighter for the frivolous or humorous. Sometimes voice is amplified by gesture such as pointing to something or spreading arms to indicate size or breadth. Gestures may be difficult for those who feel inhibited, but, well used, can offer an amplification of the voice. Imagine you are doing a radio broadcast about teaching science in the primary school. Try saying the following sentence in different tones of voice:

‘Science can be very exciting for children, because they’ll learn about some of the most spectacular phenomena in the universe; but, if they’re badly taught, science will seem a tedious chore.’

If you speak the words in a flat monotone, it will sound as dreary as the condemnation of bad teaching suggests. For effective communication you may choose to emphasise words like ‘exciting’, ‘spectacular’ or ‘badly’. You may pause after ‘but’ and slow down on the words ‘tedious chore’. Your voice may rise in pitch during the ‘exciting’ first half of the statement, and fall at the dreary foreboding of the second part.

Structure and purpose

There are several aspects of structure that are important. If an explanation has several keys in it – maybe three or four principal features that need to be brought out – then thought must be given to such matters as the sequence of ideas: how you should begin, which notion should be unwrapped or explored first, which second, which left till last and how you might conclude the explanation. These matters cannot always be fully determined in advance, because once pupils become engaged by an explanation, their questions, insights, confusion or suggestions will begin to take over and affect the process.

Questions about structure are closely related to those about teaching strategies. What use should be made of questions? (See the companion book in this series on Questioning in the Primary School by the same authors.) What is the place of a demonstration? Of practical work by the children? Of individual, group or whole-class teaching? How much and what sort of practice may be needed if the children are learning a concept, such as what a fraction is, or a skill, like how to shape a piece of wood with a file? What sort of aids to teaching might help: a picture; a video; a model or a piece of equipment?

In turn, thoughts about teaching strategies are partly contingent on the purpose of the explanation. Is it to teach a fact; a skill; a concept; a form of attitude or behaviour? In health education, for example, if children are learning about dental care, then one principal objective would be to ensure that they clean their teeth and avoid tooth decay.

The teacher may have to explain facts (what causes tooth decay, what prevents it, such as regular brushing, avoiding certain foods, using fluoride toothpaste and anti-plaque mouthwash); skills such as how to clean your teeth properly (trendy dentists nowadays recommend circular movements of the brush to follow the shape of the gum, rather than just side to side, or up and down); attitudes, like why it is worth cleaning your teeth properly (it is preferable to pain); and behaviour (ensuring that children really do clean their teeth, rather than just appear sanctimonious about it). The payoff for successful explaining of the first three – facts, skills and attitudes – would be the last, that is, ensuring behaviour which avoided needless decay and discomfort, so that the purpose of explanations in health education is often clear, even if results are difficult to achieve.

The ‘tease’

Within a certain overall purpose there may be a set of shorter-term objectives. For example, in order to give an explanation of how to avoid dental decay, the teacher may decide to make the opening gambit one which will arouse interest or intrigue the class, saying, ‘In a minute I’m going to tell you why my uncle can’t eat raspberries and walnuts any more, even though he loves them, but first I want to know if anyone’s ever had toothache.’ This device is known as a ‘tease’ in broadcasting, and many radio and television programmes begin with a tease: ‘And in a packed programme today we’ll be meeting the man who can play the oboe underwater, and we’ll be telling you how you can save thousands of pounds without effort, but first the news headlines.’ It is one of many ways of both gaining attention and shaping the presentation of information.

Activity 2

- Imagine you are starting a project on ‘Nutrition and Health’ with a class of children aged about nine, which might run for four or five weeks. Decide how you might explain what ‘Nutrition’ actually involves, asking yourself:

- What are the key concepts children will need to understand (e.g. care of the teeth? need for food for activity and growth?).

- How could I find out what children already know?

- How would I introduce the topic?

- What sort of strategies, activities, materials would I need?

- Compare your ideas with those of others in your group. What is in common and what is different? Have you identified similar key concepts/strategies?

- Try out your idea with a group of children if you have the opportunity; you can modify it, as appropriate, if you can only have them for a short period of time. Look at the following:

- Did the children already know more or less about ‘Nutrition’ than you thought they would?

- How effectively did they learn the key concepts?

- Would they, for example, be able to write or talk about human energy or about what benefits and what harms our bodies?

- If you have been able to make an audio-tape or video-tape of your session, are there any interesting events worthy of further thought – a good question you or a child asked, someone being puzzled, a good illustrative example you used?

- How would you explain the topic next time in the light of your experience?

THE PUPIL’S PERSPECTIVE

The most scintillating explanation can be wasted if the audience does not understand, or knows the facts already and so is deeply bored. There are usually at least two parties in an explanation, the explainer and what you might call the ‘explainee’, the person to whom something is being explained. Adult life is full of such pairs, and sometimes, as in classroom teaching, explanations can be reciprocal: person A explains to person B, and then, in turn, person B explains to person A.

A doctor may begin a consultation by asking the patient to explain the pain or the symptoms causing concern. At this point the patient is the explainer. Once the doctor has made a diagnosis, roles are reversed and the doctor now explains the nature of the ailment to the patient. A similar process occurs when we call in someone to mend our car or television s...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Aims and content

- Unit 1 What is explaining?

- Unit 2 Strategies of explanation

- Unit 3 Analysing explanations

- Unit 4 Knowing the subject matter

- Unit 5 Effective explaining

- Unit 6 Feedback

- References

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Explaining in the Primary School by Ted Wragg,George A Brown in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Early Childhood Education. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.