- 196 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Heritage gardens create huge management headaches. How does one preserve a garden designed for the enjoyment of the few when the advent of the many grinds it away to nothing? The answer, as presented in Heritage Gardens is a subterfuge: preserve the illusion of the created environment as originally conceived, but adjust it using more durable materials: plants and designs which require less cultivation. Of all the problems facing the heritage industry today, the managment of gardens and landscape environment create some of the greatest difficulties. This book seeks to provide some of the answers.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Heritage Gardens by Sheena MacKellar Goulty in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Museum Administration. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Background

Le monde se découvrant comme un jardin, le jardin se doit d’enfermer le monde.

Jurgis Baltrusantis

The garden heritage—source and significance

Gardens are a vital part of our national and international heritage, encompassing more facets of our cultural and social history than any other art form. Many provide the settings for historic houses, others are of interest in their own right. They are both a recreational and an educational resource and are increasingly being recognised worldwide as important national assets.

Gardens have always marked the development of civilisation. Their proliferation reflects material prosperity, their design and creation the tastes and interests of their period and cultural tradition. No study of the Italian Renaissance would be complete without an understanding of the significance of the garden within the Renaissance ideal, both as a background to a cultured life and as an expression of the balance and harmony between man and nature. The great French gardens of the seventeenth century were the ultimate expression of the power and wealth of their owners; their decay and neglect after the Revolution reflected political change and the downfall of the aristocracy. Indeed, to a large extent, interest in gardens and gardening in France died with the Revolution, little being written on French gardens in French thereafter, and only recently has there been a revival of general interest among the French public.

On the one hand, gardens are our most accessible art form, but on the other, the form in which it is most difficult to interpret the original intentions of the designer. They can be enjoyed on many levels, from the simple enjoyment of being outdoors in a pleasant environment, to an appreciation of their plants, or of their design and history, but, by their very nature, gardens are ephemeral. Most represent an overlapping kaleidoscope of change, through the seasons, through the growth, decay and renewal of their plant material and through the changes wrought by successive owners or designers. Yet they are arguably one of the best sources for the social historian, embodying, as they do, so many different elements, the art of the designer, the skills of craftsmen and gardeners, the cultural and social status of the owner.

If the conservation of our garden heritage is to be successful, it is essential to be clear about its purpose. Unlike archaeology, garden restoration can never be an exact science. Too much depends on transient elements, so that it is a continuing process, requiring constant adjustment and upkeep. A large part of its aim must be the enjoyment of users today, but we also owe to future generations the conservation of an important artistic and historic resource. Decisions about whether to conserve, restore or reconstruct must be taken within a historic and national or cultural context.

Historic development

The art of garden design has always borrowed from different periods and countries, but although historic influences cross national borders, separate gardening traditions developed within distinct geographic and cultural boundaries. For example, the English landscape style was only practised on a minor scale in Scotland, to whose more dramatic natural topography it was unsuited, and where, perhaps owing much to the customary excellence and practical ability of Scottish gardeners, as well as a natural conservatism, a formal gardening tradition continued, particularly in the immediate environs of the house. In America the English landscape style made most impact within the great American park movement, since it was land in public rather than private ownership that lent itself to the grand scale of an informal landscape.

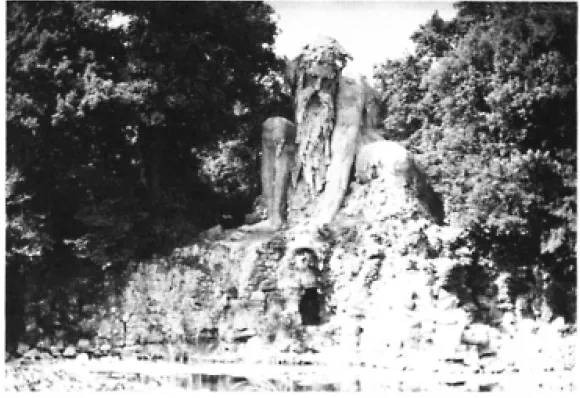

On the continent the fashion for the ‘English garden’ led to the sweeping away of many of the more grandiose, high maintenance, formal schemes, although some of the built elements of the formal layout would often remain in uneasy alliance with the new informal landscape as in the Medici garden at Pratolino in Italy. In other places an ‘English garden’ was added to the side of a formal layout, as at Schwetzingen in Germany, where an eclectic range of garden features married the formal to the informal in a way that led eventually to the mockery of the ‘jardin anglais’ 1 by English travellers abroad. At its best, for example in the park at Marly, Paris, now known as the Désert de Retz, with its twenty garden buildings related in a landscape setting, a combination of influences from two very different informal styles, the English and the Chinese, led to the emergence of the style known as ‘anglo-chinois’.

1 ‘Il colosso dell’Appennino’ in the Medici garden at Pratolino

Conservation of heritage gardens in Europe and America is usually concerned with those created since the Renaissance. On the whole, conservation applied to pre-medieval gardens is meaningless; they belong to the realm of archaeology. But the Renaissance garden looks back to the classical authors for its inspiration, to Homer and the ‘Elysian fields’, and to its immediate predecessor, the medieval garden, whose form and symbolism reflect the Persian ‘paradise’ or enclosed garden.

Early gardens were enclosed by a fence or wall, or terraced, in either case the boundary being clearly defined, separating the cultivated garden from encroaching nature, whether that meant the desert to the great early civilisations of Mesopotamia and Egypt, or wandering livestock to the medieval monastic community. The medieval enclosed garden represented both the earthly paradise of biblical times, the Garden of Eden and the garden of love portrayed in the Song of Songs, and also a celestial or spiritual paradise. The imagery of the Song of Songs, the garden as the bride, was combined with the Marian interpretation of the garden as the Virgin Mary with Christ as the gardener.

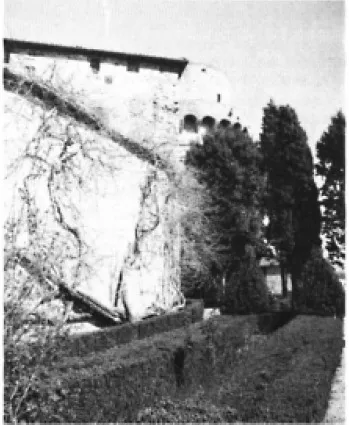

Such enclosed gardens existed not only within the monastery walls, but also within the defensive walls of medieval castles. The garden at Edzell in Kincardineshire, Scotland, survives as a late example of a castle garden on this scale. Although the planting is a creation of the 1930s, it was built in 1604 within the space bounded by the old moat, and is surrounded on three sides by defensive walls which are decorated with niches. The medieval castle of Trequanda in Tuscany, dating from the twelfth century, also contains a garden in the triangular space between its outer defensive and inner walls, although whether it was always planted as a garden is uncertain. The locals know the garden as the ‘Bosco inglese’, which suggests that it owes its current form to the Victorian revival of interest in Italian gardens.

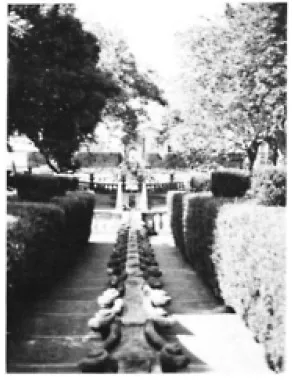

Whereas the humanist gardens of the early Italian Renaissance were still walled or terraced, they were no longer secluded from the outside world, but rather embraced the view and the advantages of an elevated site. The importance of the view, the choice of site, and its integration with the landscape relate back to Roman descriptions of gardens, and also forward to the writings of the eighteenth century, such as the unpublished poem ‘The Country Seat’, by Sir John Clerk of Penicuik, describing the ideal siting and design for a country residence, and Alexander Pope’s ‘Epistle to Lord Burlington’ which advocated the encouragement of the ‘spirit of the place’. Leon Battista Alberti’s De re aedificatoria, explaining how a country house and its gardens should be planned, based on the writings of Pliny and written between 1450 and Alberti’s death in 1472, was well known and widely influential even before it was printed in 1485. The small garden of the Palazzo Piccolomini in Pienza, built in 1459, is typical of the transition in garden design of this period. It is in effect an outdoor garden room to one side of the palace, with arched openings in the boundary hedge for the view.

The simplicity of these garden rooms was suited to the hilly Tuscan countryside and to Tuscan taste, more subtle than its Roman counter-part, so that the creation of this type of garden continued for longer in Tuscany than elsewhere. The garden of the Villa Capponi at Acetri, which dates from the second half of the sixteenth century, has three original ‘rooms’, a grassed terrace at the back of the house giving a view of Florence and the Arno from one end, a lemon garden opening off the other end, and a walled garden with windows, which was originally entered only through an underground passage from the house. The garden of the Villa Gamberaia, Settignano, is a typical Tuscan gem. Founded in 1610, although it probably assumed its present form in 1717, the villa is approached along a cypress walk. On the west of the villa is a grassed terrace with a magnificent view of Florence. To the south is a parterre garden, now a water garden but still retaining the traditional Renaissance layout of four parterres divided by paths, with a fountain in the circular space at the crossing. The bowling green runs the length of the grounds on the east. A small giardino segreto opens off the centre of it, with a lemon garden and a shady bosco above and to either side. Water is ducted into a grotto framed by cypress trees at one end of the bowling green. The other end is balustraded and overlooks the valley of the Arno and the olive groves, which come right up to the garden wall.

2 The castle garden at Edzell whose decorated walls date from 1604

3 The ‘Bosco inglese’ of the medieval castle at Trequanda

The siting and the planting were the most important elements in the design of Renaissance gardens in Tuscany; the architectural element was incidental. Two Medici gardens, however, were exceptions to this rule, the Boboli and Pratolino. These had a definite architectural form like the great Roman gardens, an extension of architecture into the landscape. The Boboli gardens survived the ravages of the English landscape style, probably because the plan is so well related to the topography of the site. The gardens were for public rather than private entertainment, and in the early seventeenth century, the addition of tiers of seats around an open space used for pageants revived the classical relationship between the theatre and garden design.

4 The garden ‘room’ of the Palazzo Piccolomini, Pienza

The great water garden of the Villa d’Este at Tivoli, commissioned from Piero Ligorio in 1550 and completed in the 1580s, is considered to be the most typical example of a Roman High Renaissance garden. The full effect of the rising terraces and the splendid variety of water features must be viewed from the foot, but at each level there is spectacle, not only in the jets and fountains, grottos and water channels, but also in the vista across the Campagna. The Villa Lante at Bagnaia was designed by Vignola in 1564, and beautifully restored in 1954, since when it has won a well deserved reputation as the best kept garden in public ownership in Italy. It has a similar ‘feel’ to a Tuscan garden owing to its more intimate scale, but the use of water is entirely in the Roman tradition, although it is less flamboyant than at the Villa d’Este, making a play of the constant gentle movement of water along a central axis which recalls the Moorish gardens of southern Spain. The villa is divided into two parts and set halfway up the slope, on either side of the main axis, giving an unrivalled unity to the architectural composition of the garden. The prospect from the garden overlooks the rooftops of the borgo of Bagnaia in the foreground, and the central axis of the piazza meets that of the garden at the main entrance gate. This relationship between the village and the main approach to the villa was exploited by François Mansart in the siting of the French château of Balleroy, built in the 1620s, where the village street became an extension of the axis of the château.

5 Villa Capponi from the lemon garden

The interplay of light and shade created by evergreen planting, the cooling effects of water, and the interest provided by stone sculpture and architectural details are the essence of the Italian Renaissance garden. The importance of shade, or the want of it, is highlighted in the restoration of the Medici garden at Castello. The lunette, painted by Giusto Utens between 1599 and 1602, depicts a central bosco around a circular pool. The replanting of this feature would have mitigated the current lack of charm about the garden by putting back the vertical accent, as well as giving an essential element of shade in a very flat, open space.

Although the shade of a bosco or planted walks was a vital part of the Italian garden, the more formal or architectural elements, in particular the parterre, were planned nearest the house. The parterre was intended to be viewed from above. Renaissance designs were geometrical, unlike the curving forms of the later French ‘broderie’, and laid out with evergreen herbs. Box was not widely used until after 1600 when its more enduring, if not endearing, qualities (its smell was unpopular) were found useful in forming the more intricate French designs. A fine example of a parterre dating from the end of the sixteenth century still exists at the Villa Ruspoli at Vignanello. The design is close to examples in Sebastiano Serlio’s treatise Architettura, printed in 1537. It was laid out by Ottavia Orsini, and her initials are incorporated into the design of the central bed near the castle. It was originally planted in rosemary, but replanted in box early this century.

6 One of the terraces of the water garden of Villa d’Este, Tivoli

7 The cascade on the central axis of the Villa Lante, Bagnaia

8 The château at Balleroy which dominates the axis of the village street

In spite of the fact that a combination of various evergreens made up the basic structure of planting in these Italian gardens, the planting of flowers played a much greater part than is generally realised. The parterre pattern was usually of simple geometrically-shaped beds in order to display the flowers. The Medici family introduced many new plants to their gardens, and the layouts of the beds used to display their collections can be seen in Utens’ lunettes. In 1545 the first botanic garden was founded in Padua, and by 1552 there were already 1,500 species cultivated in the garden. The garden still retains its original form, and even some of the sixteenth-century plants, within the circular boundary wall. Here the beds are edged with stone rather than herbs. The botanic garden also has fine examples of wrought iron, a decorative material typical of the Veneto, in the form of plants and flowers which once adorned the gate posts.

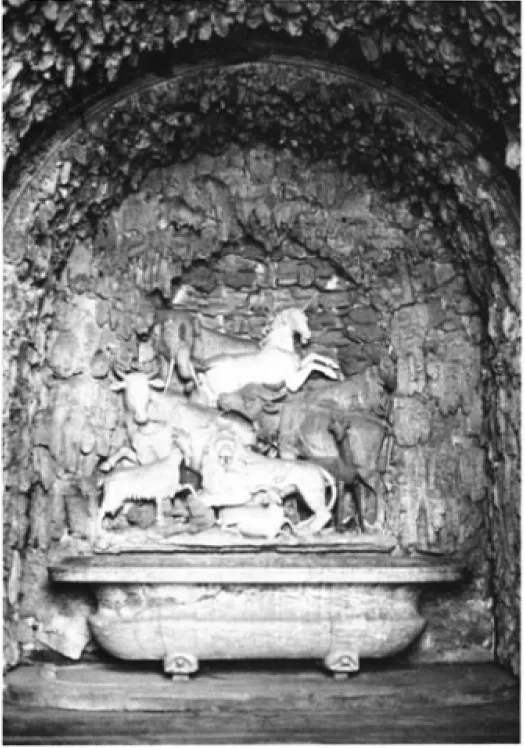

Italian Renaissance gardens were well known outside Italy. A visit to Italy was regarded as an essential part of the education of a gentleman. One such traveller, Fynes Moryson, wrote a detailed account of his travels through Europe, An Itinerary, published in 1617. He describes the gardens at Pratolino and Castello, and elaborates on the grottos, fountains and water-controlled automata. His description of Buontalenti’s grotto at Castello amply illustrates the delight taken in ‘giochi d’acqua’ (water jokes) in this period, as well as showing that a guided tour round a garden is nothing new:

Here in another Cave are divers Images of beasts of Marble, curiously wrought, namely of Elephants, Camels, Sheepe, Harts, Wolves, and many other beasts, admirable for the engravers worke. Here our guide slipped into a corner, which was only free from the fall of waters, and presently turning a cock powred upon us a shower of raine, and therewith did wet those that had most warily kept themselves from wetting at all the other fountains.

It was not only travellers, but also war, that spread the Italian influence in garden design. In 1495 the French king, Charles VIII, revived his claim to Naples and Sicily, and invaded Italy. The invasion was shortlived but Charles, impressed by the cultural riches of Italy, and particularly by the gardens of the Poggio Reale where he stayed in Florence, brought back Italian artists and craftsmen to work in France. The influence of Italian culture was strengthened by further Italian expeditions under Louis XII and Francis I, and by the marriage of Henri II to Catherine de Medici.

9 ‘Divers Images of beasts of Marble’ in Buontalenti’s grotto at Castello

The engravings of Jacques Androuet du Cerceau’s plans and drawings, printed in Les Plus Excellents Bastiments de France in 1576 and 1579, are the best available reference for the Renaissance garden in France. Dr Joachim Cavallo’s early twentieth-century re-creation of the gardens at Villandry, in the sixteenth-century style, was based on designs from this source. Few French Renaissance gardens survive, but at Chenonceaux the gardens of Diane de Poitiers and Catherine de Medici still exist on either side of the main, northern approach to the château, which is built out into the river, with a two-storey gallery on the bridge continuing the axis into the park on the south bank. These gardens were known to the young Queen of Scots, Mary Stuart, since a festival was held at Chenonceaux ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Illustrations

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Glossary

- 1 Background

- 2 The Conservation Process

- 3 Maintenance and Management

- 4 Case Studies

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Selected Sources of Further Information

- Further Reading