- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Art in the Early Years

About this book

For all involved in teaching young children, this timely book offers the necessary tool with which to develop a broad, creative and inspirational visual arts programme. Presented in two parts, this text covers both theoretical and practical angles:

- part one investigates contemporary early childhood art education, challenging what is traditionally considered an early years art experience

- part two puts theory to text by presenting the reader with numerous inventive visual art lessons that imaginatively meet goals for creative development issued by the QCA.

The author strikes the perfect balance between discussion of the subject and provision of hands-on material for use in lessons, which makes this book a complete art education resource for all involved in early years art education. Teachers, trainee teachers, or nursery teachers, who wish to implement a more holistic art curriculum in the classroom whilst meeting all the required standards, will find this an essential companion.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Art in the Early Years by Kristen Ali Eglinton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Early Childhood Education. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Contemporary early childhood art education

Chapter 1

Setting the scene:

The why, what, and how of early years art education

INTRODUCTION

Art in the early years – the phrase evokes images of young children in colourful aprons up to their elbows in school paint, bright marks on paper clipped to a child-sized easel, little hands furiously pounding, squeezing, or moulding some malleable medium, the unmistakable feel of crayons or smell of play dough. Yet, though scores of us recollect these quintessential childhood art experiences, there is much more to the artistic education of young children than the splashing of paint, or the manipulation of art media. Some of the art lessons children partake in, while devised by educators with the best intentions, often fall short of delivering any educational or developmental benefits. As Part I of this text demonstrates, art in early childhood is often characterised by activities that offer little more than a chance to, perhaps, get messy, or play with art media. What is more, the common non-interventionist approach of merely sitting a child in front of a lump of clay, although seemingly educationally sound, can ultimately lead to boredom and dissatisfaction. Partly because of this widespread practice and narrow view of what art in early childhood could potentially offer, many educators fail to understand the importance of art in the early years, and possess, at best, only a vague notion of how to support the artistic learning of young children.

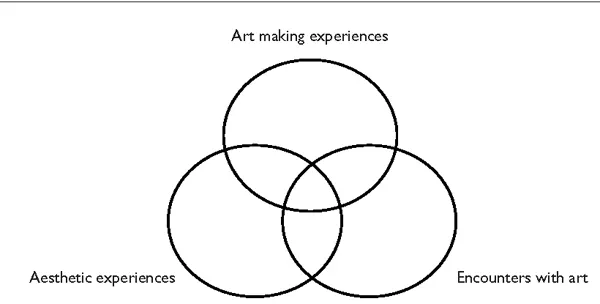

This book extends the limited definition of what is traditionally considered an artistic experience – art production or the making of form – and takes a more expansive and holistic approach further incorporating aesthetic experiences (experiences with beauty), and encounters with art (reflecting on and growing from works of art, craft, and the like). In a holistic art programme, the three types of art experiences form a highly related structure, in which all of the elements in the model influence each of the other elements. Art making might include a previous encounter with art or sometimes an aesthetic experience will spark an idea for art making. Art making, encounters with art, and aesthetic experiences work together, their union forms a comprehensive art programme. This relationship is demonstrated in Figure 1.1.

In the model presented, all artistic experiences are dynamic; experience leads to more experiences; discovery generates further investigation. However, art experiences are only dynamic if educators play an active role. The educator propels the experience by engaging children in dialogue, stimulating them through motivation, observing children when they make art, talk, and play, employing documentation, and reflecting on art products. In this approach, art experiences work like a web, each discovery, interest, and dialogue is connected, taking children to new meaningful artistic endeavours.

Figure 1.1 Artistic experiences and a comprehensive art programme include art making experiences as well as aesthetic experiences and encounters with art. In a holistic programme, all three components are integrated

Part I of this book is devoted to addressing art’s essential role in the early years, and to offering educators the theoretical, historical, and ideological base from which they can create their own educational early years art programme. Included is an exploration of erroneous teaching practices, an in-depth study of artistic experiences, the ‘process’, art making experiences, and motivation and dialogue (Chapter 2), aesthetic experiences and encounters with art (Chapter 3), the role of documentation (Chapter 4); and art for special needs (Chapter 4). Finally, Chapter 5 thoroughly examines the early learning goals for creative development issued by the Qualifications and Curriculum Authority (QCA) (2000), and looks at implementation of those goals into effective art in the early years practice. Part II of this text offers readers a multitude of sound educational artistic experiences.

A few explanations, clarifications, and comments before beginning; first, this book continuously refers to children in the ‘foundation stage’: children aged 3 to 5 or to the end of reception year. This does not mean, however, that with slight modifications the basic principles and practices explored in Part I and the experiences in Part II are not applicable in some form to a wide range of ages. Further, even within the Foundation Stage, the varying ages and levels of development will require educators to adjust the offered methods and experiences. Second, the terms educator, staff, and teacher are used interchangeably, they include, but are not limited to, anyone involved or interested in the arts education of young children: teachers, nursery nurses, teacher trainers, nursery staff and managers, students of childcare and early years study, parents, school administrators, art education students, and the like. Third, settings in this book are referred to as classrooms, nurseries, or early years environments, to name a few. This expansive view enables educators to envision an art programme in their own particular teaching situation. Finally, though it is not required, a thoughtful read of Part I is highly recommended before embarking upon the experiences presented in Part II.

WHY ART?

Whereas the educational importance of a maths or reading programme is rarely questioned, one can safely assume when promoting and implementing a comprehensive visual arts agenda, educators will find much of their precious time used justifying the need for art in education. Experience reveals handfuls of meetings spent tirelessly defending the positive consequences of an extensive arts curriculum. Some educators are fortunate, on their side are like-minded people who support the idea of art in education; yet, we frequently find that many of these like-minded supporters have a limited understanding as to why art is so essential to a child’s education. They recognise that experiences with art should be available to children, but remain unaware of the vast opportunity for development embedded in art experiences. In order to create an art programme or even one simple art experience, it is imperative that we understand both the character of art and the developmental opportunities housed in artistic experiences – it is only when we know why we teach art that we can teach it in a truly worthwhile way.

There are many reasons why educators supply children with art media or supplies. Objectives range from sensory exploration to the exercising of the imagination. Observation and experience demonstrate that in the pre-school and nursery, sensory stimulation, as an artistic objective, is at the top of the list. This is a wonderful aim. Art experiences do stimulate the senses; however, the idea is to go deeper, to expose the depth and breadth of potential goodness tucked away inside artistic experiences. Eisner (1972: 2) describes two educational rationales for engaging in art experiences: the ‘contextualist’ and ‘essentialist’. The contextualist looks first at the context in which the art programme will unfold, and, after considering the surrounding circumstances, creates art experiences to fill the recognised need. The objectives of the art programme are fashioned on ‘who the child is, what type of needs the community has, what problems the larger society is facing’ (ibid.: 3). The contextualist will teach art, for example, to build self-esteem, unleash creativity, or as a tool in the enrichment of another subject such as science or maths.

The essentialist, on the other hand, creates an art programme based on the nature of art itself; the essentialist ‘emphasizes what is indigenous and unique to art’ (ibid.: 2), and believes ‘that the most important contributions of art are those that only art can provide’ (ibid.: 7). The essentialist examines the distinguishing features of art and bases the art programme on those characteristics. Sharpening the senses, heightening perception, the giving of form to ideas and thoughts, and the fostering of aesthetic awareness are some examples of what only art can contribute.

An examination of the contextualist objectives and the essentialist rationale is a good starting point for studying the reasons why we teach art. Looking closely at the contextualist aims, one is reminded of pre-school and nursery settings, community art projects, and numerous non-learning establishments such as crèches or after-school clubs. Art projects are justified as facilitators of physical development, as a way to build the self-esteem of the children, or as a project for the betterment of the community, fulfilled, for example, by the fabrication of a community mural where young and old have an opportunity to work together. There should be no mistake, these are excellent reasons for promoting the arts; not only are they valid, they also expose children to some of the many benefits of art. However, there is much more to art than merely the opportunity to, say, hone fine motor skills or build community spirit. The following section describes some of the major reasons for teaching art. A number of the justifications are quite detailed, others only touched upon; the reasons for teaching art are so numerous and diverse it is impossible to explain each one in detail in this particular text. See Table 1.1 for an overview of the justifications.

The senses

Both the contextualist and the essentialist agree that the senses and the subsequent stimulation of them are a just rationale for the teaching of art. The senses do more than feel, see, hear, smell, and taste; the senses connect us with the environment. From birth, a person explores the environment through the senses; the senses are in essence the channels through which we extract information from the environment and, consequently, learn. Lowenfeld and Brittain (1987: 11) state, ‘It is only through the senses that learning can take place.’ Moreover, most inspiration, stimulation, and information come from sources outside us. One can argue that, perhaps, all internal experiences, including the formulation of original ideas, are sparked by external stimuli. Yet, as Eisner (1985) points out, in education the nurturing of the senses is overlooked in the quest for the advancement of the mind. How the senses came to be divorced from learning is a matter best left to the educational historian. For our purposes, suffice to say that art experiences reconnect the senses with learning. How? Art experiences, when properly facilitated, serve to sharpen and cultivate sensory awareness. Sensitivity to our environment does not just happen, Lowenfeld and Brittain (1987) explain that the senses need to be properly educated to see subtly and distinction, to feel gradations, to become truly aware of our surroundings. Rich and worthwhile art experiences awaken and ultimately guide the senses.

Table 1.1 Overview, reasons for teaching art in the early years

Perceptual development

Keiler (1977: 19) describes perception as ‘the significant impression which an object or an event produces on the mind through the various senses’. Keiler (ibid.: 19) adds, we ‘exercise discrimination’ in perception. He explains that this distinction is caused by our being ‘impressed by one particular aspect of perceived reality than by any other’. It is based on this phenomenon that Keiler attributes the difference between looking and seeing. How does all this theory answer the question, why art? What does perception and perceptual discrimination have to do with art in early childhood? The answer comes in two parts.

First, art provides the material that enables the growth of a child’s perceptual discernment. Looking at, reflecting upon, creating, and experiencing art teaches, guides and refines perception. Second, perception is not limited to impressions through the senses; true perception requires thought. Taking this notion a step further, Arnheim (1969) demonstrates in his book Visual Thinking, the inextricable link between thought and perception; he reveals that thinking is fed by perception and perception by thought. Since a large portion of perception is visual, this uncovered relationship has huge implications for the arts, namely the visual arts (Arnheim 1983). If thinking and perception are tied, it follows then that the active perception, which is part of art experiences, is more than just looking – it is thinking, learning, and as Arnheim (1983) concludes, understanding vital visual and conceptual relationships. The visual arts provide a place for the child to look, think, understand, and learn.

Aesthetic awareness

Educators and authors involved in early childhood art often point out the difference between using the word aesthetic as a noun and employing it as an adjective (Hagaman 1990; Herberholz and Hanson 1995). The word aesthetic as a noun refers to a branch of philosophy that examines the nature of art and artworks, as an adjective, the word simply means relating to and/or an appreciation of beauty. In Chapter 3 we look closer at aesthetics and its involvement in early childhood art; for now, it is sufficient to say, in the early years we are concerned with the word aesthetic as an adjective – again, relating to and/or an appreciation of beauty.

When we use the word as an adjective, it becomes easy to appreciate the notion that art education aids in the growth of aesthetic awareness. When children are taught how to sense and perceive with refinement and skill, they are more apt to recognise or discover beauty or, we will call it, the aesthetic in objects and experiences that before held little interest as an actual aesthetic object or experience. Lowenfeld and Brittain (1987: 129) describe aesthetics as ‘a basic way of relating oneself to the environment’. They believe that forming a sensitivity to the environment, including how we perceive it visually, feel it, and live in it is in fact the development of aesthetic awareness.

Art opens children up to the infinite aesthetic objects and experiences that present themselves everyday. If we fail to support the recognition of beauty, a child’s world can soon become barren and undistinguished, inspiration and stimulation over time are replaced with passivity and disregard for both the natural and shaped environment.

Cognitive development

Cognitive development is described by Papalia and Olds (1993: 29) as the ‘changes in children’s thought processes that result in a growing ability to acquire and use knowledge about their world’. Cognitive development applies to art in two respects. First, the child is constantly interacting with the environment, learning how to look, feel, and ultimately express. It is in this continuous interaction that the child will form a deeper understanding of the world, better methods for extracting vital information, and formulate new and original ways to give visual form to their experiences, thoughts, and ideas. Second, as Gardner (1990: 9) reasons, looking at, and creating art require a child to arrive at the encounter equipped with basic methods for both ‘decoding’ and creating symbols. This symbolic activity rooted in art created and reflected upon is indicative of arts cognitive contribution.

The remaining justifications for the teaching of art, while just as important as those previously described, are mentioned here briefly. Furthermore, though numerous school subjects can target some of these remaining areas, art continues to be an excellent vehicle for their facilitation. They include, communication in a visual language, the use of intuitive thinking, and the perpetuation of culture and art’s rich history (see Chapter 3 for an in-depth look at art history and the transmission of culture), language development, personal and social development, and creative growth.

Our understanding of the educational benefits of art experiences and the deeper awareness of why we teach art provide us with the foundation on which to construct artistic experiences. However, before beginning this construction, we look at why we must often rally support for an art programme that stretches beyond the traditional concept of childhood art.

WHAT HAPPENED TO ART EDUCATION?

Baker (1992) found that although 50 per cent of nursery time in the ten schoo...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- ILLUSTRATIONS

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- PART I: CONTEMPORARY EARLY CHILDHOOD ART EDUCATION

- PART II: IDEAS INTO PRACTICE: ARTISTIC EXPERIENCES FOR THE FOUNDATION STAGE

- REFERENCES