![]()

PART I

Masculinity in Question

![]()

1

“The First Bond Who Bleeds, Literally and Metaphorically”

Gendered Spectatorship for “Pretty Boy” Action Movies

Janet Staiger

My fascination with “pretty boy”1 movies began around 2003 when a group of friends went to see Pirates of the Caribbean (Gore Verbinski, 2003). Afterwards, two other women of about my age and I enjoyed drinks, sharing our pleasures in watching Johnny Depp, I attracted in particular to his rather bold choices in starring roles and his unique and memorable interpretations of the characters, but my friends also delighted in him for their own reasons. Soon the three of us began regularly seeing all films in which he starred and named ourselves the Deppettes. I might also reveal here that this is the only “fandom” in which I participate.

Luckily, Depp is recruited for many roles, but occasionally when we want to see a film, we are Depp-rived.2 While we have favorite genres as an alternative to a Depp movie, one of our first options is to see movies with “pretty men.” We have standard tastes here; however, I was the one to think that Daniel Craig justified going to see Casino Royale (Martin Campbell, 2006). Although I shall be using myself as a source of response, an auto-ethnographical move, some of the public reception of the film surprised me.3 In particular, in a fan chat room, one person confessed to crying, and others replied that they had as well. I certainly had no such reaction although I found the film an exciting reboot of the franchise. While in retrospect I believe that I can account for some of the critical and fan reception of Casino Royale, the case may be illustrious of some contemporary male spectatorship of male action-adventure films, one of the most powerful and successful genres today. In particular for this chapter, I shall be focusing on reports by males of crying and their related attributions of realism for the film. I shall also discuss what I believe to be a related, inverted formula and its success with female audiences. While somewhat theoretical, this chapter remains a historical materialist reception studies account since I am contextualizing the space of reception and noting current trends of filmmaking that affect viewers’ horizons of expectation.

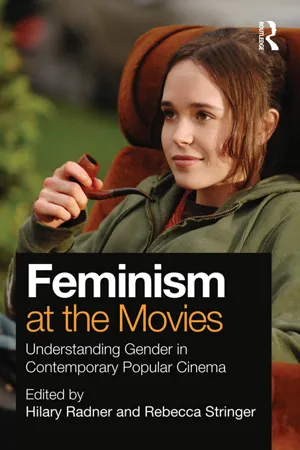

FIGURE 1.1 “Pretty boy” Johnny Depp in Pirates of the Caribbean: At the World’s End (2007). Courtesy of Sony Pictures/Photofest.

The 2006 Casino Royale begins with James Bond earning his double-0 with his first two kills. He tracks down Le Chiffre (Mads Mikkelsen) who is financing terrorists. With the help of an MI6 accountant, Vesper Lynd (Eva Green), and despite his egotism (about which both M and Vesper caution him), Bond wins Le Chiffre’s money at Monte Carlo. Afterwards, Le Chiffre tortures Bond for the password to the bank account where the money is stored, but at the last moment he and Vesper are saved. Vesper and Bond enjoy an idyllic moment, and Bond says he is going to turn in his resignation papers so they can be together; however, when they are to transfer the funds to MI6, it appears that Vesper has conned him. That turns out not to be true: Le Chiffre was holding her former boyfriend in exchange for the funds, and she arranges for Bond to re-secure the money and kill Le Chiffre, but she dies, in a suicidal act, and “Bond, James Bond” is “born.”4

The Male Weepies5

Let me begin my analysis with the reports of crying. In an Internet Movie Database (IMDb) thread, “Who cried?

Spoilers

,”

6 emzy64 starts with the statement,

Okay it might be just me, but I found the ending reallyyy sad. I was literally bawling my eyes out; mainly because of the fact that the love story was so developed and you could tell they really loved each other … then suddenly, its all over and she dies.

When he’s trying to revive her on the rooftop, oh, that was so sad! Maybe it’s just because over the course of the movie I grew to love Vesper’s character so much and so, her death affected me deeply.

Everytime I watch it now, I think “noo please don’t die” but then I guess if she didn’t, we wouldn’t have a series of James Bond novels. I don’t know which one I’d prefer though.

While I do not know the sex of emzy64, the three people who reply use login names or replies that imply they are male, and comments in the responses reinforce this. Donald_Hai writes,

I agree it was very sad, but I think Vesper had to die in order for James Bond to forever become numb … Tragic Bond

.

JustAMessageBoardPoster2 says:

I am a guy and I am not ashamed to admit I am a sucker for that stuff. I cried.

I chalk it up to Green. Her subtly nuanced and layered performance as well as her absolutely unearthly beauty just had my heart breaking right along with Bond when Vesper dies.

Royale Green contributes:

I am in complete agreement … I got very choked up at the end and especially … especially when he tried reviving her. [He used CPR.] …

Such a sad ending, but it’s a necessity for the franchise.

Of course, not all males cried, or probably more than a few.7 The space for these confessions needs to be considered. I was in the Internet Movie Database, which is certainly friendly to male participants. Moreover, Henry Jenkins notes the typicality of these sorts of exchanges. He writes, “Entries [in net groups] often began with ‘Did anyone else see …’ or ‘Am I the only one who thought …,’ indicating a felt need to confirm one’s own produced meanings through conversations with a large community of readers.”8 Still the response and the writers’ rationale for the narrative events are worth some attention.

Casino Royale is in the mode of the melodramatic. Using the arguments of Linda Williams and Rick Altman,9 scholars recognize that it is analytically fruitful to see melodramatic characteristics of narrative and narration as pervasive across numerous genres.10 Laura Mulvey and Tom Schatz have discussed melodrama within westerns and 1950s family stories with male protagonists; John Mercer and Martin Shingler, amongst others, note that action movies are ripe for melodrama.11 In extending this work, I have argued that a parallel to the “fallen woman” story exists in the “fallen man” formula, which is used in many film noirs and superhero movies.12 In the fallen man formula,

plot devices lure a man into wayward paths because of his lack of control. These lures may be drink or gambling or even blind ambition; they are often sex, perhaps motivated as derived from a femme fatale tricking, seducing, or forcing the man into his wayward path … the male protagonist may be able to redeem himself.13

A really good example of the fallen man formula is Casablanca (Michael Curtiz, 1942), which very much resembles Casino Royale, with the hero detoured from his proper path in fighting the enemy by a woman he loves and whom he mistakenly believes betrays him, but who turns out to have loved him very much. She, however, must be sacrificed so that he can head off and “wed” his country. The cult of Casablanca lays bare the emotional appeal to men (and to women, of course) of this formula. Williams emphasizes that a large number of action films with male victim-heroes “pivot upon melodramatic moments of masculine pathos. … And when the victim-hero doesn’t win, the pathos of his suffering seems perfectly capable of engendering what Thomas Schatz … has termed a good ‘guy cry.’”14

An important part of the fallen-man plot is the pathos of suffering that in recent years has laid itself upon the beautifully sculpted naked body of the male victim-hero/star. Since I am just beginning this research I can only discuss Casino Royale, but from my random film viewing I am guessing that it is fairly typical. As a reviewer of the film panted, “the numerous shots of [Craig’s] torso and piercing blue eyes will, I suspect, make many in the female audience extremely happy.”15 Some males as well, I would add:Netflix reviewer FrankenPC writes, “I had to question my sexuality after watching this movie. Daniel Craig is hot. Steaming hot!”16

Casino Royale exploits Craig, with the first naked chest shot a lovely leisurely reveal: Bond slowly rises out of the sea, standing momentarily against the blue water. What follows is the beginning of a seduction sequence with a beautiful black-haired woman in a green bikini riding bareback on a magnificent white horse. Ah, the opportunities for identification and desire!

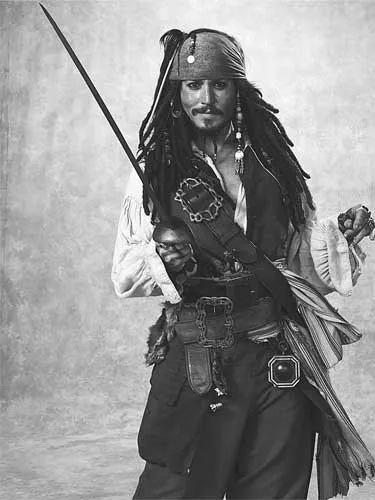

FIGURE 1.2 Daniel Craig as “James Bond” in Casino Royale (2006). Courtesy of Artina Films/Photofest.

The Male Body and the Male Heart

Since melodrama is never complicated—John Cawelti notes it employs “an arsenal of techniques of simplification and intensification”17—it is upon the body that pain is inflicted. The value of the routine of body torture of male protagonists in fallen-men stories is transparent: Mel Gibson in the Lethal Weapon (Richard Donner, 1987; 1989; 1992; 1998) series, Bruce Willis in Die Hard (John McTiernan, 1988) (think of the walk across broken glass). Neal King comments: “The outrageous beating fantasies and sexual/violent penetrations of male bodies present peculiar visions of political order of ‘mourning in America,’ to say the least.”18 King and Fred Pfeil attribute this body torture to cultural crises in masculinity, with Pfeil noting (in line with Steven Neale and others) that the punishment for these fallen men involves “simultaneous feminization and spectacularization.”19

Miriam Hansen, however, explores further this melodramatic technique, considering what is at stake for the case of Valentino—another bare-chested victim-hero who is often whipped in his films. Arguing for case-by-case analysis, she claims that the Valentino appeal “sets into play fetishistic and voyeuristic mechanisms”20 and reveals “the fascination with and suppression of ethnic and racial otherness,” a “cult of consumption and [a] manifestation of an alternative public sphere.”21 Hansen explains the pleasures of the torture scenes by referring to Freud’s “A Child is Being Beaten” story.22

Although displays of cultural crises and sado-masochistic fantasies might explain part of the enjoyment of watching the body of Bond in Casino Royale— one Netflix writer comments, “This Bond is battered, bruised and shaken and the rest of us are stirred”23—that explanation does not do much to account for the crying, and those explanations were not meant to, especially since the IMDb writers specifically attribute their sadness to the loss of the girl, another mechanism for making the male suffer. In fact, the IMDb males tolerate body pain, but not heart pain.

Mercer and Shingler note that Neale explains tears at happy endings as “due to the fulfillment of our own infantile fantasy (crying being a demand for satisfaction and our tears sustaining that fantasy),” but for unhappy endings, tears are “a product of powerlessness.”24 Williams disagrees with that theory for sad endings. She argues, “[W]e cry when something is lost and it cannot be regained.” Thus, “because tears are an acknowledgement of hope that desire will be fulfilled, they are also a source of future power. … Mute pathos entitles action.”25

Williams’s thesis seems to me a bit optimistic in terms of what a spectator might be projecting. Williams refers to an essay by Franco Moretti on crying over literature. Moretti writes, “Tears are always the product of powerlessness” against reality, but tears simultaneously shield us from viewing such a “resignation,” instead creating anger about the reality and creating a “communal weeping” amongst the survivors.26 “Crying enables us not to see” as well as provoking “definitive sadness, because the loss is definitive; and at the same time relief, because, if nothing else, all inner conflict has ceased.”27 So Moretti’s view is a bit more cautionary than the conclusion that Williams draws.

Still, I would prefer to backtrack just a bit. Although Hansen does not reference Elizabeth Cowie’s earlier work on Freud’s story of “A Child is Being Beaten,” Cowie’s discussion of fantasy provides great assistance in understanding what is going on in these fallen-men melodramas. Cowie argues that a fantasy is a structure, a “mise-en-scène of desire.”28 The fantasy she analyzes allows for multiple points of identification and positions of desire in the scenarios of seduction and masochism. But Cowie also notes, “defences [sic] are inseparably bound up with the work of fantasy.” She recounts a case discussed by Freud in which the female client describes a story of desire, but as the story unfolds she is punished and ends up crying. Cowie asks, “But why has she produced a story to make herself cry, and may not the tears be a response not to the pathos of the story but to its satisfactions? The crying thus acting as a defence, brings the fantasy to the end in the same way Freud speaks of waking oneself up from the dream.”29 The woman’s fantasy h...