eBook - ePub

Matter, Materiality and Modern Culture

Paul Graves-Brown, Paul Graves-Brown

This is a test

Share book

- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Matter, Materiality and Modern Culture

Paul Graves-Brown, Paul Graves-Brown

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Matter, Materiality and Modern Culture offers a new approach to the study of contemporary objects, to give the reader a new understanding of the relationship between people and their material world. It asks how the very stuff of our world has shaped our societies by addressing a broad array of questions including:

* why do Berliners have such strange door keys?

* should the Isle of Wight pop festival be preserved?

* could aliens tell a snail shell from a waste paper basket

* why did Victorian England make so much of death and burial?

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Matter, Materiality and Modern Culture an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Matter, Materiality and Modern Culture by Paul Graves-Brown, Paul Graves-Brown in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Scienze sociali & Archeologia. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

THE BERLIN KEY OR HOW TO DO WORDS WITH THINGS1

Bruno Latour

A social dimension to technology? That’s not saying much. Let us rather admit that no one has ever observed a human society that has not been built with things. A material aspect to societies? That is still not saying enough;things do not exist without being full of people, and the more modern and complicated they are, the more people swarm through them. A mixture of social determinations and material constraints? That is a euphemism, for it is no longer a matter of mixing pure forms chosen from two great reservoirs, one in which would lie the social aspects of meaning or subject, the other where one would stockpile material components belonging to physics, biology and the science of materials. A dialectic, then? If you like, but only on condition that we abandon the mad idea that the subject is posed in its opposition to the object, for there are neither subjects nor objects, neither in the beginning – mythical – nor in the end – equally mythical. Circulations, sequences, transfers, translations, displacements, crystallisations – there are many motions, certainly, but not a single one of them, perhaps, that resembles a contradiction.

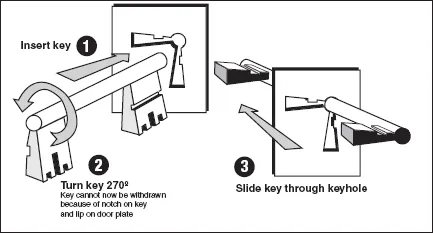

In Carelman’s Catalogue des objets introuvables (Carelman 1995) one does not find the surrealistic key that appears below – and for good reason. This key does exists, but only in Berlin and its suburbs.2

Here is the sort of object which, though it may gladden the hearts of technologists, causes nightmares for archaeologists. They are in effect the only ones in the world to study artefacts that somewhat resemble what modern philosophers believe to be an object. Ethnologists, anthropologists, folklorists, economists, engineers, consumers and users never see objects. They see only plans, actions, behaviours, arrangements, habits, heuristics, abilities, collections of practices of which certain portions seem a little more durable and others a little more transient, though one can never say which one, steel or memory, things or words, stones or laws, guarantees the longer duration. Even in our grandmothers’ attics, in the flea market, in town dumps, in scrap heaps, in rusted factories, in the Smithsonian Institution, objects still appear quite full of use, of memories, of instructions. A few steps away there is always someone who can take possession of them to pad those whitened bones with new flesh. This resurrection of the flesh may be forbidden to archaeologists, since the society that made and was made by these artefacts has disappeared, body and goods. Yet even if they must infer, through an operation of retroengineering, the chains of associations of which the artefacts are only one link, as soon as they grasp in their hands these poor fossilised or dusty objects, these relics immediately cease to be objects and rejoin the world of people, circulating from hand to hand right at the site of the excavations, in the classroom, in the scientific literature. The slightly more resistant part of a chain of practices cannot be called an ‘object’, except at the time it is still under the ground, unknown, thrown away, subjected, covered, ignored, invisible, in itself. In other words, there are no visible objects and there never have been. The only objects are invisible and fossilised ones. Too bad for the modern philosophers who have talked to us so much about our relations with objects, about the dangers of objectification, of auto-positioning of the subject and other somersaults.

Figure 1.1 Ceci est une clef

As for us, who are not modern philosophers (and still less post-modern ones), we consider chains of associations and we say that they alone exist. Associations of what? Let us say, as a first approximation, of humans (H) and non-humans (NH). Of course, one could still make a distinction, on any given chain, between the old divisions and the modern. H-H-H-H-H would resemble ‘social relations’; NH-NH-NH-NH-NH a ‘machine’; H-NH a ‘person-machine interface’; NH-NH-NH-NH-NH-H ‘the impact of a technology on a person’; H-H-H-H-NH ‘the influence of society on technology’; H-H-H-NH-H-H-H the tool shaped by the human, while NH-NH-NH-H-NH-NH-NH would resemble those wretched humans crushed by the weight of automatisms. But why endeavour to recognise the old divisions if they are artificial and prevent us from following the only thing that matters to us and that exists: the transformation of these chains of associations? We no longer know just how to characterise the elements that make up these chains once one has isolated them. To speak of ‘humans’ and ‘non-humans’ allows only a rough approximation that still borrows from modern philosophy the stupefying idea that there exist humans and non-humans, whereas there are only trajectories and dispatches, paths and trails. But we know that the elements, whatever they may be, are substituted and transformed. Association – AND – substitution – OR: this is what will give us the precision that could never be given us by the distinction between social and technological, between humans and things, between the ‘symbolic dimension’ and ‘material constraints.’ Let us allow the provisional form of humans and the provisional essence of matter to emerge from this exploration through associations and substitutions, instead of corrupting our taste by deciding in advance what is social and what is technological.

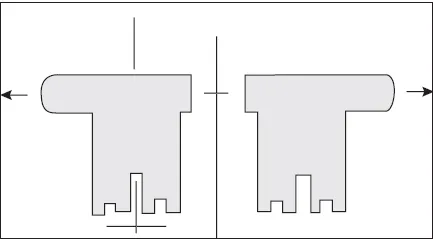

‘What is this thing? What’s it used for? Why a key with two bits? And two symmetrical bits? Who are they trying to kid?’ The archaeologist turns the Berlin key over and over in her hands. Because she has been told, she now knows that this key is not a joke, that it is indeed being used by Germans and that it is even used – the detail is important – on the outer doors of apartment buildings. She had certainly spotted the side-travel allowed by the fact that the two bits were identical, and the lack of asymmetry in the teeth had struck her. Of course she was aware, because she had been using keys for a long time, of their usual axis of rotation and felt clearly that one of the bits, either one, could serve as a head in order to exert enough leverage to disengage the bolt.

Figure 1.2 Berliner key symmetry

It was only afterwards that she noticed the groove. The latter did not break the side-travel but re-established an asymmetry when she considered the key in profile. However, by turning the key 180° on its vertical axis, one found the same groove at the same place. Translation, 360° rotation on the horizontal axis, 180° on the vertical axis – all this probably meant something, but what?

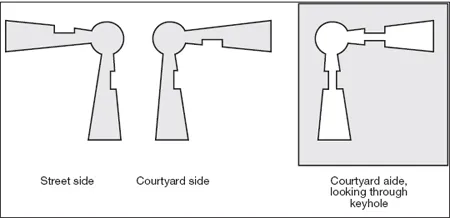

There had to be a lock for this key, she felt sure. It was the lock that would provide the key to this little mystery. However, when she looked at the hole into which it was to be engaged, the mystery only increased.

She had never before seen a keyhole shaped like this, but it was clear to her that the whole business, the whole affair, was based on the arrangement of the notch of the horizontal hole that would or would not allow the hole to receive the groove in the key.

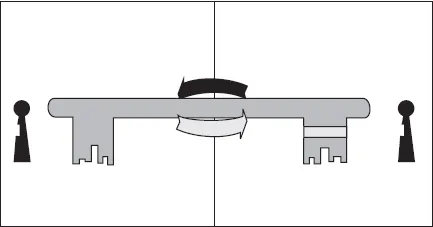

Our archaeologist’s surprise was still greater when she was unable to withdraw the key after having introduced it vertically and having turned it 270° counterclockwise. The lock was certainly open, the bolt had certainly retracted into the black box as in the case of any honest lock, the outer door was certainly opening, but try as she might, to pull, push, twist her key, our friend could not extract it again. The only way out, she found, was to lock the door again by a 270° clockwise rotation. And so she found herself locked out again, back where she started. ‘What foolishness!’ she says to herself. ‘In order to get my key back, I have to lock the door again. Yet I can’t stay behind the door, on the courtyard side, while I bolt it again on the street side. A door has to be either open or closed. And yet I cannot lose a key each time I use it, unless the door in question is an asymmetrical one that has to remain unbolted while one is inside. If it were a key to a mailbox, well, then I could understand it. But this is absurd, anyone could lock me in with a turn of the key, and anyway, we’re talking about the door to an apartment house. And on the other hand, if I bolt the lock without the door being closed, the bolt will stop it from closing. What protection can a door offer if it is carefully bolted but wide open?’

Figure 1.3 Berliner key reversibility

Figure 1.4 Berliner keyhole

Good archaeologist that she is, now she sets about exploring the specifications of her miraculous key. What action would permit her to preserve all the elements of common sense at once? A key serves to open and close and/or to bolt and unbolt a lock; one cannot lose one’s key each time, nor leave it inside, nor bolt an open door, nor believe there would be a key to which a locksmith had, just for fun, added a bit. What gesture would allow one to do justice to the particularity of this key – two bits symmetrical through 180° rotation around the axis and identical through side-travel? There must be a solution. There is only one weak link in this little socio-logical network. ‘Damn, of course!’ A reader avid for topology, an inhabitant of Berlin, the astute archaeologist, have probably already understood the gesture that must be made. If our archaeologist cannot withdraw her key after having bolted the door by a 270° rotation as is her habit with every key in the world, she must be able to make the key, now horizontal, slip from the other side through the lock.

She tries this absurd move, and actually succeeds. Without underestimating our archaeologist’s mathematical aptitudes, we can bet that she might remain standing at the door of her building the whole night through before learning how to get in. Without a human being, without a demonstration, without directions, she would certainly have an attack of hysterics. These keys that pass through walls are too reminiscent of ghosts not to frighten us. This gesture is so unhabitual that one can only learn it from someone else, a Berliner, who has in turn learned it from another Berliner, who in turn … and so on and so forth by degrees all the way back to the inspired inventor, whom I will call, since I don’t know him, the Prussian Locksmith.

Figure 1.5 Key operation – street side

If our friend were fond of symbolic anthropology, she could have consoled herself for not being able to get in by endowing this key with a ‘symbolic dimension’: in West Berlin, before the Wall fell, the people supposedly felt so locked in that they doubled the number of bits on their keys. ‘There, that’s it, a repetition compulsion, a mass psychosis of the besieged, a Berlin–Vienna axis; hm, hm. I can already see myself writing a nice article on the hidden meaning of German technological objects. That is certainly worth spending a cold night in Berlin.’ But our friend, thank God, is only a good archaeologist devoted to the harsh constrains and exigencies of objects.

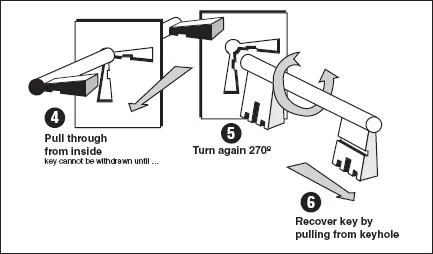

She finds herself on the other side of the door again, the key still horizontal, and feels that she will at last be able to recover it. ‘That’s the Germans all over’, she says to herself. ‘Why make something simple when you can make it complicated!’

However, just when she thought she was out of the woods, our archaeologist once again comes close to a fit of hysteria. Once she and her key – one in a human manner, the other in a ghostly manner – have passed to the other side, she still cannot recover her sesame. In vain she pulls, pushes, there is nothing to be done, the key is no more inclined to come out than it was when one engaged it on the other side. Our friend can find no other solution than to go back to where she started, on the street side, by pushing the wall-penetrating key back through in a horizontal position, then once again bolting the door, finding herself back outside, in the cold … with her key!

Figure 1.6 Key operation – courtyard side

She starts everything over again from the beginning, and finally sees (someone has shown her; she has read some sort of directions; she has groped around for a long enough time) that by bolting the door again behind her, on the courtyard side, she is at last authorised to recover her key. Oh joy, oh delight, she understands how it works!

These shouts of joy were premature.When, in the morning at around ten o’clock, she wanted to show her friend what a good Berliner, as well as a good archaeologist, she had become, she covered herself with shame. Instead of demonstrating her brand new attainments, she could not turn the key more than five degrees. This time, the door remained open permanently without her being able to bolt it. It was only at ten o’clock at night, when she came back from the movies, that she could exercise her know-how, for the door, as it had been the night before, was hermetically sealed. She was forced, then, to participate voluntarily in this hermeticism by bolting it behind her in order to recover her precious key.

It was only at eight o’clock in the morning the next day that she met the concierge; as he withdrew his key from the door he gave her the key to the mystery. The caretaker’s passkey had no groove, was thinner, and in quite the classical manner had only one bit. The concierge, and he alone, could bolt or unbolt the door as he pleased, by inserting his ke...