![]()

Part I

Climate change: A psychological problem

The principle task of civilization, its actual raison d’être is to defend us against nature … But no one is under the illusion that nature has already been vanquished; and few dare hope that she will ever be entirely subjected to man. There are the elements which seem to mock at all human control; the earth which quakes and is torn apart and buries all human life and its works; water, which deluges and drowns everything in turmoil; storms, which blow everything before them … With these forces nature rises up against us, majestic, cruel and inexorable; she brings to our mind once more our weakness and helplessness, which we thought to escape through the work of civilization.

(Freud 1927: 15–16)

We make no distinction between man and nature … man and nature are not like two opposite terms confronting each other … rather they are one and the same essential reality, the producer-product.

(Deleuze & Guattari 2000: 4–5)

![]()

Chapter 1

Climate crisis

Psychoanalysis and the ecology of ideas

The ecological crisis is the greatest threat mankind collectively has ever faced … [which] with rapidly accelerating intensity threatens our whole planet. If so staggering a problem is to be met, the efforts of scientists of all clearly relevant disciplines will surely be required … psychoanalysts, with our interest in the unconscious processes which so powerfully influence man’s behavior, should provide our fellow men with some enlightenment in this common struggle.

(Searles 1972: 361)

The planetary crisis

The Fourth Assessment Report of the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC 2007: 5) concluded that human activities are affecting the Earth on a planetary level, with ‘atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide’ now far exceeding anything ‘over the past 650,000 years’, including a rise in greenhouse gas emissions of ‘70% between 1970 and 2004’. Fourteen of the 15 warmest years on record occurred in the last 14 years (the other was 1990, which was warmer than 1996) (Brohan et al. 2006, from the UK Met Office, 2009), and the first decade of the twenty-first century, 2000–2009, was the warmest decade ever recorded (Voiland 2010), with the 2001–2010 period being even hotter (World Meteorological Organization 2011). The scientific consensus is now overwhelming, with no major scientific body disputing the seriousness of the situation.

Warming of the climate system is unequivocal, as is now evident from observations of increases in global average air and ocean temperatures, widespread melting of snow and ice and rising global average sea level … evidence from all continents and most oceans shows that many natural systems are being affected … Most of the observed increase in … temperatures since the mid 20th century is very likely due to the observed increase in anthropogenic (human) greenhouse gas concentrations … The probability that this is caused by natural climatic processes alone is less than 5% … temperatures could rise by between 1.1 and 6.4 °C … during the 21st century … Sea levels will probably rise by 18 to 59 cm … [P]ast and future anthropogenic carbon dioxide emissions will … contribute to warming and sea level rise for more than a millennium … [but] the likely amount … varies greatly depending on the intensity of human activity during the next century.

(IPCC 2007: 2–5)

We have so altered the physical processes of the Earth that future geologists, should they still exist, will be able to identify a clearly distinct period of the Earth’s history for which a new term was introduced at the start of this millennium, the ‘anthropocene’ (Crutzen & Stoermer 2000; Zalasiewicz et al. 2008; Revkin 1992). Between 20,000 and 2 million species became extinct during the twentieth century, and the rate is now up to 140,000 per year in what is labelled the sixth major extinction event to have occurred in the last 540 million years (Morell & Lanting 1999), the first to be caused by the activities of a single species. Harvard biologist E. O. Wilson, in The Future of Life (2003) warns that half of all known species could be extinct by the end of the century. The 2010 UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), held in Japan, increased the number of officially endangered species on the ‘Red List’ to now include one fifth of all animal and plant species (including 41 per cent of amphibians). Major extinction events should also not be seen as linear processes, as beyond certain critical thresholds entire ecosystems can be brought to a state of collapse, and can take ten million years to recover (Science Daily 2011; Whiteside & Ward 2011).

We are taking part in a planetary pyramid scheme, getting into an ecological debt from which there can be no bail outs. Yet somehow this just doesn’t hit home, our behaviour doesn’t match our knowledge. Why? In what we might call a ‘deficit’ account of our inactivity, George Marshall (2005, 2001) claims we have a faulty ‘risk-thermostat’ and so are unable to grasp the abstractness of the issue. To try to get more of a handle on what global temperature rises might do, George Monbiot (2005) makes it more concrete:

We know what these figures mean … but it is very hard to make any sense of them. It just sounds like an alteration in your bath water … The last time we had a six degree rise in temperature … around 251 million years ago in the Permian Era, it pretty well brought life on earth to an end. It wiped out 90% of all known species … Virtually everything in the sea from plankton to sharks simply died. Coral reefs were completely eliminated not to reappear on earth for ten million years … On land, the ground turned to rubble … vegetation died off very quickly, and it no longer held the soil together … [which] washed … into the sea … creating anoxic environments at the bottom of the ocean … [There was a] drop in total biological production of around 95% … Only two quadrupeds survived … We are facing the end of human existence … this is a very, very hard thing for people to face.

Here we are on more psychoanalytically interesting (if emotionally terrifying) territory, suggesting an ‘anxiety-defence’ understanding of inactivity. Monbiot (ibid.) continues, asking why we can accept the threat of terrorism and the related changes to our lives, but not the far greater threat of climate change. There has been a marked shift over the past decade. In public statements, politicians and major business groups are increasingly united on the importance of the issue (if not its policy implications). Yet despite growing consensus, little is actually being done. Years of positive speeches by the UK government, for example, and claims of substantial – even ‘world-leading’ – reductions disguise the fact that CO2 emissions from overall British economic activity have actually continued to rise, due in part to growing consumer demand. In addition, many of the claimed ‘reductions’ have come more from structural changes in global economic production (including so-called ‘carbon outsourcing’) than from actual efficiency savings.

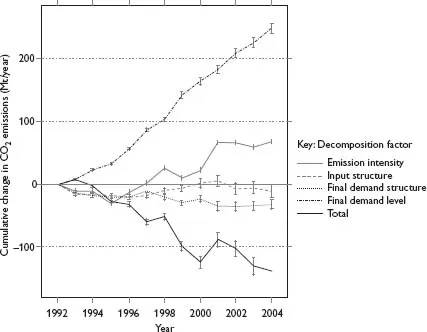

This has been dramatically demonstrated by Baiocchi & Minx (2010: 1177; see Figure 1), who applied structural decomposition analysis (SDA) to a global multiregional input-output model (MRIO) of changes in UK CO2 emissions between 1992 and 2004. They found that while ‘improvements from domestic changes in efficiency and production structure led to a 148 Mt reduction in CO2 emissions’ this ‘only partially offsets emission increases of 217 Mt from changes in the global supply chain’ including from the phenomenon of carbon outsourcing, and ‘from growing consumer demand’ (ibid.).

The 2009 Copenhagen Summit, billed as the epoch-making turning point when the world would come together to save the planet – it was even dubbed ‘hopenhagen’ (Brownsell 2009) – was all but a complete failure (Vidal 2009). Even the Kyoto Protocol, seen as a more successful agreement, has not led to any actual reductions in global carbon emission rates, which grew by 24 per cent between the 1997 agreement and 2005 (World Bank 2010: 233). In the context of climate change, the gap between knowledge and action does not seem to be narrowing, and it is becoming increasingly clear that what is most needed is psychological research, for it is ultimately in human thinking, feeling and behaviour that the problem is generated, and can potentially be solved.

Figure 1 Decomposition of annual changes in the UK’s carbon footprint for the 1992–2004 period in millions of tonnes of CO2 per year

Source: Baicchi & Minx 2010, 1179

Psychological approaches to environmental problems

Psychology is now waking up to the fact that it offers the ‘missing link’ in climate change science (Schmuck & Vlek 2003; Oppenheimer & Todorov 2006; Reser 2007). This book offers primarily a psychoanalytic approach, which is particularly sensitive to dealing with issues around emotion, anxiety, and defences, as well as subtle psychological processes not easily captured on survey questions. In other words it emphasizes the unconscious psychological dimension of our individual, group, and social lives. However, it is important to emphasize that all areas of psychology have something important to offer towards this effort, and indeed the crisis is so acute that no one approach will be enough in the face of the immensity of the task at hand (Winter & Koger 2004). All need to participate in the wider ecology of ideas. Psychoanalysis, with its focus on the unconscious aspects of behaviour, needs to have a prominent place in this important work.

What are some of the non-psychoanalytic psychological approaches to climate change and environmental problems? Schmuck and Vlek’s (2003) review of the literature explores various areas where psychology can play an important role. One approach is to study environment problems as dilemmas of the commons (Hardin 1968; Ostrom 1990; Vlek 1996), sometimes referred to as social dilemmas (Dawes 1980; Dawes & Messick 2000; Osbaldiston & Sheldon 2002). These are situations involving a conflict between collective interests, or the aggregate interests of a large number of people (including potentially future generations of people as yet not born), and short-term individual interests.

This area is continuing to be developed in more focused work on the environment, for example Van Vugt’s (2009) ‘Averting the Tragedy of the Commons: Using Social Psychological Science to Protect the Environment’. Evolutionary psychology (Buss 2004, 2005; Barkow 2006; Tooby & Cosmides 2005) argues that in such situations while it may be in the interest of each individual for everyone else to follow the rules which benefit the group as a whole, it is not necessarily in the individual’s own interest to do so themselves (Ridley 1997; Axelrod 1984). In addition, while many individuals may discount the importance of their own negative impact on the common physical or social environment, the cumulative effect of many such small impacts leads to significant environmental problems.

Given that over-consumption of the Earth’s resources is a key root of the ecological crisis, consumer psychology also has much to offer. Traditionally, consumer psychology has studied consumers wants and needs, and has understandably been used to help businesses to better predict, satisfy and – crucially – produce consumer demand for their products. Clearly, this is an area where psychology has been part of the problem, in that it has aided the effort to encourage the over-consumption which is so threatening the planet today. However, it has also developed a body of knowledge and techniques which its exponents suggest can now be turned to the task of developing pro-environmental behaviour. In addition, consumer psychological research has shown that increased consumption (beyond a minimum level) has no positive correlation with increased happiness (Csikszentmihalyi 1999; Durning 1995). On the contrary, according to Schmuck and Vlek (2003), evidence suggests that ‘self-centered consumer values, life goals, and behaviors’ have been ‘associated with detrimental effects for individual well-being’ (Cohen & Cohen 2001; Schmuck & Sheldon 2001).

Turning to cognitive psychology, studies of cognitive biases (Haselton, Nettle & Andrews 2005; Finucane et al. 2000) suggest that individuals tend naturally to focus on short-term gains rather than long-term goals, especially under situations of uncertainty (Kahneman, Slovic & Tver 1982), an area where effective action in the face of climate change is obviously relevant (Yudkow 2006; Pawlik 1991). Given these obstacles to action, how can psychology engage with these biases and help towards individual and social change?

Albert Bandura applied social learning theory and social cognitive theory (Bandura 1986, 2002) to an intervention designed to decrease population growth, ultimately one of the key drivers of many of the environmental problems we face. Social learning theory suggests that our behaviour is affected not only by direct reinforcers or punishments or behaviour shaping, as explored in classical and operative conditioning in the behaviourist tradition (Skinner 1969, 1981; Watson 1970; Baum 2005), but also indirectly by observing others (modelling, observational learning) and the rewards or punishments they receive (vicarious reinforcement). This is, after all, how advertising works. We are often shown people who are beautiful, happy and successful (in terms of love and wealth) following purchase of the item concerned.

Based upon these concepts, Bandura arranged a series of broadcasts in several regions with high population growth rates which showed the advantages of small families and the disadvantages of large families. Controlled studies demonstrated that these interventions led to an increased preference for small families, an increased use of contraception, and a clear drop in birth rates. Discussing this successful psychological campaign, Bandura writes:

One of the central themes … is aimed at raising the status of women so they have equitable access to educational and social opportunities, a voice in family decisions and child bearing, and serve as active partners in their familial and social lives. This involves raising men’s understanding of the legitimacy of women making decisions regarding their reproductive health and family life.

(Bandura 2002: 222)

Environmental psychology (Gifford 2007) and the psychology of human–environment interactions have traditionally focused on the built environment with less emphasis on the natural environment and ecology (Scull 1999). However, this is now beginning to change. Stern (2000) suggests that many psychological theories have clear applications to the environmental crisis, some of which have already been applied. These include cognitive dissonance theory (e.g. Katzev & Johnson 1983, 1987), norm-activation theory (e.g. Black, Stern & Elworth 1985; Stern et al. 1999; Kalof 1993; Widegren 1998), and the theory of reasoned action or the theory of planned behaviour (e.g. Bamberg & Schmidt 1999; Jones 1990).

Stern (2000, 2004) has attempted to integrate much of this research into a more detailed understanding of pro-environmental behaviour. He suggests that given the urgency of the situation, psychological research and interventions should be targeted on areas likely to have the biggest impact, for example in decisions related to purchases of environmentally impactful items such as houses, domestic heating and cooling equipment, and cars. According to Stern (2000: 527) ‘one-time decisions can have environmental effects for decades because of the long life of the equipment (Gardner & Stern 1996; Stern & Gardner 1981).’

One crucial area where psychological research can inform environmentalists is research on the effects of traditional environmental campaigns which use fear to frighten us into action. Stern (2005: 5) points out, however, that much of the research into the effect of such appeals in general has been far from supportive of this approach (Finckenauer 1982; Higbee 1969; Johnson & Tver 1983; Weinstein, Grubb & Vautier 1986), arguing that:

The best ev...