![]()

1

A CHILDHOOD IN FLAVIAN ROME

On the ninth day before the Kalends of February, when the consuls were the Emperor Vespasian, for the seventh time, and Titus Caesar, for the fifth time, a son was born at Rome to Domitia Paulina, wife of the young senator Aelius Hadrianus Afer. Thus the Historia Augusta (HA) records the birth of the future emperor Hadrian, on 24 January of the year 76 – at Rome, rather than at Italica in southern Spain, the home of his father. For senators their official domicile was Rome and most of them, particularly those holding or seeking one of the traditional magistracies, did indeed reside there. Cassius Dio registers the father’s name as Hadrianus Afer, describing him as a senator and ex-praetor. That might simply mean that Afer reached the praetorship in the course of his career. But it is likely enough that he had been praetor a year or two before Hadrian was born. Chance has preserved on papyrus part of a letter Hadrian wrote to Antoninus just before his death: he mentions that his father lived only to his fortieth year. Afer died when Hadrian was in his tenth year, the HA reports, and was thus twenty-nine or thirty when his son was born, precisely the standard age for the praetorship. He could have held the office earlier. Augustus’ legislation allowed senators a year off the minimum age for magistracies for each child, and Afer also had a daughter, named after her mother, probably older than Hadrian.1

Neither the HA nor other sources offer further details on Hadrian’s first nine years – except for a single inscription, which records the name of the future emperor’s wet-nurse, Germana, no doubt a slave. Like other women of high rank, Paulina did not breast-feed her son. Germana, to judge from her name, may have been of northern barbarian origin. She was later given her freedom and would outlive Hadrian. The vita does supply a single telling detail about Hadrian’s mother and considerable information on his father’s family. Domitia Paulina ‘came from Gades [Cádiz]’. This was the oldest city in Spain and, according to tradition, the earliest of all the Phoenician settlements in the west, going back to the late second millennium BC. After centuries of independence and indeed dominance in southern Spain, Gades had fallen under Carthaginian control at the latest in the time of Hannibal’s father Hamilcar Barca. After a few decades Gades switched allegiance during the Hannibalic War and was received by Rome into alliance in 206 BC. Several of its sons became Roman citizens. The most prominent was L. Cornelius Balbus, who achieved immense influence as Caesar’s agent and after the dictator’s death was actually made a member of the Roman Senate and consul in 40 BC, the first consul not to have been Italian born. In the meantime Caesar had conferred citizenship on the entire community. Gades’ wealth was proverbial. Balbus himself had been extremely rich. In the Augustan age there were five hundred Gaditani with the equestrian property-qualification. Several men from these families must have followed Balbus into the Senate. One may readily postulate that Domitia Paulina’s father, if not indeed earlier generations of the family, had achieved this rank. The ultimate descent was, of course, Punic: the family name Domitia points to descent from a person enfranchised through the good offices of one of the noble Republican Domitii.2

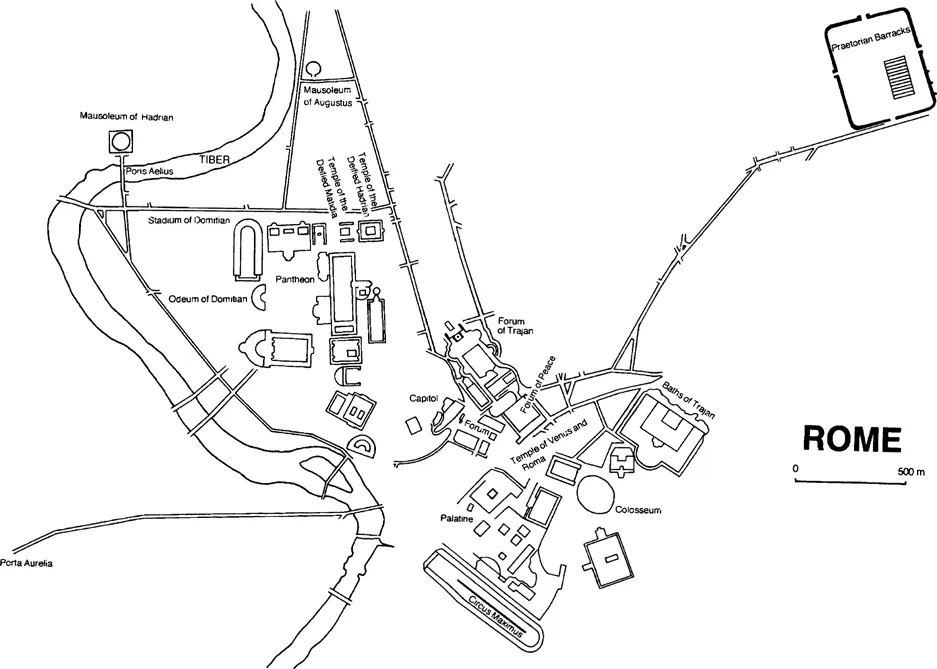

Map 1 Rome: the city centre

The paternal line was very different. The Aelii had been settled at Italica, some 5 miles (8 km) upstream from Hispalis (Seville), since ‘the time of the Scipios’. In other words, an ancestor had been one of the sick or wounded soldiers’ of P. Cornelius Scipio’s army in Spain, left behind in a new settlement when he was about to return to Rome in 206 BC – the same year in which Gades had received its treaty-status – ‘in a town which he named Italica after Italy’. The place was not a colonia, although it would later become a municipium, and the soldiers were doubtless allied Italians, not Roman citizens. The first Aelius of Italica came from Hadria on the east coast of Italy, as Hadrian was careful to note in his autobiography. Some two hundred years later, a member of the family, Hadrian’s atavus Marullinus, his great-grandfather’s grandfather, had entered the Roman Senate. Hence, even if the intervening generations did not serve as Roman senators, the Aelii were certainly one of the leading families of Italica, indeed of the whole province of Baetica. Two other Italica families with whom they shared this position may be identified, the Ulpii and the Trahii or Traii, the ancestors of Trajan. One or both derived from Tuder (Todi) in Umbria, and, like the Aelii, their settlement at Italica probably went back to the foundation in 206 BC.3

Hadrian’s link with Trajan is stressed in the HA, his father Hadrianus Afer being described as ‘a cousin (consobrinus) of the Emperor Trajan’. It is generally assumed that Hadrian’s grandfather had married an aunt of Trajan, or, to put it another way, a sister of the elder Trajan, M. Ulpius Traianus. This man, who was thus Hadrian’s great-uncle, was one of the most powerful and influential persons of the day. He was in the east at the time of Hadrian’s birth, as governor of Syria, and his son, Hadrian’s father’s cousin, was with him, as a military tribune. Traianus owed his distinction in part, no doubt, to his military capacity, but also to a fortunate chance: he had been commanding X Fretensis, as one of the three legionary legates in the expeditionary force in Judaea led by Vespasian from late 66 onwards. Hence he was one of the men on the spot when his commander-in-chief was proclaimed emperor in July 69. Two other legionary legates in Judaea in this expedition had been a man from Vespasian’s home town, Reate (Rieti), Sex. Vettulenus Cerialis – and Vespasian’s own son Titus. It looks as if Vespasian had been allowed to choose these two legates himself – a most exceptional circumstance. Perhaps Traianus was also Vespasian’s choice. There are hints that his wife Marcia owned property at the confluence of the Tiber and the Nar, equidistant between Tuder and Reate; and Marcia may have been a sister of Titus’ first wife Marcia Furnilla. Be this as it may, as an old comrade-in-arms of the Emperor and of his elder son Titus Caesar, Traianus had a status in the 70s that was clearly exceptional. Besides, as governor of Syria he demonstrated his prowess, deterring a threatened Parthian invasion.4

The Aelii and Ulpii were no doubt wealthy. Membership of the Senate after all demanded a substantial property qualification. The Aelii – it is no surprise – owned productive olive plantations upstream from Italica. During the Civil Wars of 49–45 BC men from Italica had played a prominent role in the Spanish campaigns – but mostly on the side of the Pompeians. It may be conjectured that Hadrian’s ancestor Marullinus had supported Caesar and that he acquired senatorial rank as a reward. The rise of the colonial élite – in particular from Gallia Narbonensis and from Baetica – continued under the Julio-Claudian dynasty, accelerated by the influence of the Guard Prefect Afranius Burrus of Vasio (Vaison-la-Romaine) and Annaeus Seneca of Corduba (Córdoba), Nero’s principal advisers for the first part of his reign. That Nero’s immediate successor Galba had been for many years governor of Hispania Tarraconensis at the time of his proclamation in 68 gave a further boost to the fortunes of the Spanish Romans; and Vespasian had signalled a new step forward in 73–4 when he conferred Latin status on all Spanish communities that were not yet Roman or Latin.5

Thus ‘colonial’ magnates had held the highest offices at Rome in some numbers by the time of Hadrian’s birth. Valerius Asiaticus of Vienna (Vienne) had been consul ordinarius (holding office for the second time) in 46. Pedanius Secundus of Barcino (Barcelona) had even been Prefect of Rome under Nero. In the mid-70s there were several dozen families from the western provinces in the ranks of the Senate – joined by a handful from the Greek-speaking east who had jumped on the Flavian bandwagon in 69. As censors in 73 and 74 Vespasian and Titus had even granted patrician status, membership of the primeval aristocracy of Rome, to some provincials. Among those favoured were the Ulpii Traiani, the Annii Veri from the Baetican colonia of Ucubi (Espejo), Cn. Julius Agricola from Forum Iulii (Fréjus) in Narbonensis, who would shortly be consul (perhaps in 76, a few months after Hadrian’s birth) and then governor of Britain, and, from Gallic Nemausus (Nîmes), the brothers Domitii, Lucanus and Tullus.6

Hadrian’s family presumably spent the winters at Rome and the hot summer months at a cooler suburban retreat. The odds are that they already had, or would soon acquire, a villa at Tibur (Tivoli), where there was a cluster of Spanish notables with country houses in the Flavian period. Whether Hadrian’s parents took him back to the old family home in his early childhood is rather doubtful. Contact with Italica and supervision of the family estates in Baetica could have been largely dealt with through bailiffs. Senators were expected to live at Rome, their official place of residence, except when on government service elsewhere. Besides, Hadrianus Afer, as a recent praetor, must be assumed to have held several posts in public service in the years immediately following his son’s birth. Command of a legion is a strong possibility – up to half of the praetors each year would be called upon, particularly since Vespasian evidently made the praetorship a preliminary qualification for this post (previously younger men had become legionary legates, as in the case of Titus, legate of XV Apollinaris at the age of twenty-seven, having gone no further than the quaestorship). This could have been followed by the governorship of one of the ‘imperial’ provinces, as pro-praetorian legatus Augusti – thus Julius Agricola, praetor in 68, legate of a legion in Britain and then, for a little less than three years, governor of Aquitania.7

Less demanding posts were also available, for example, for twelve months only, as legate to one of the ten proconsuls, and then another twelve months – according to the rules, no earlier than five years after the praetorship – as proconsul of one of the eight proconsular provinces reserved for ex-praetors. The majority of the proconsulships were of provinces in the Greek-speaking half of the empire. One of the few proconsular provinces in the west was Baetica – which Traianus had governed under Nero. The legate or proconsul would certainly take his wife and children with him, furthermore. Hence there is a distinct possibility that Hadrian, as a child, spent a year or two in the Greek east. This remains no more than a guess. It may, nonetheless, be noted that Traianus was proconsul of Asia in 79–80. The proconsuls of Asia and Africa were drawn from the ex-consuls and the former could nominate three legati. One of Traianus’ legates is known, T. Pomponius Bassus, who might have been a fellow-Spaniard. Another was probably one of the new Greek senators, A. Julius Quadratus of Pergamum. The third — it is no more than a guess — could well have been the proconsul’s nephew, Hadrianus Afer.8

That the child Hadrian could have accompanied his parents to Ephesus, Smyrna and other ancient and opulent cities of the province Asia is at least worth a thought. Childhood impressions are important and most people’s earliest memories go back to about the age of three or four. Even more enticing is the thought that Afer could easily have been proconsul of Achaia in the early 80s, when Hadrian would have been a boy of four or five. Still, there is no need to invoke such speculation to explain how someone who grew up in Flavian Rome would be so attracted to all things Hellenic. Rome was by then – and had been indeed for over a century – in a real sense the largest Greek city in the world. That is to say, in the same way that at one time Glasgow was the largest Irish city or New York had the largest Jewish population, the Greek-speaking inhabitants of Rome had probably long outnumbered those of any Greek polis in the east. Greek culture in the capital had been further boosted by Nero’s enthusiastic philhellenism and had not declined with his downfall. Some of it was no doubt very superficial, such as the fashion of having trained slaves to recite Platonic dialogues as entertainment at dinner-parties. But there was genuine enthusiasm for Greek literature, philosophy and art. Greek intellectuals such as Plutarch found a ready welcome in Flavian Rome. As for Latin literature of the age, the titles of Statius’ Thebaid and Achilleid, or Valerius Flaccus’ Argonautica, speak for themselves. It is worth recalling that Quintilian, the foremost teacher of his day, recommended that small boys – he was thinking, of course, of the élite – should be taught Greek before Latin (which they would pick up anyway), although not to the extent of ‘speaking and learning only Greek for a long time – as happens in very many cases’. This would have a bad effect on the child’s command of Latin. The common practice which Quintilian thought excessive may well have applied to the boy Hadrian.9

If the three-year-old Hadrian was at Rome, rather than at Ephesus or elsewhere with his father in the summer of 79, the death of old Vespasian and the accession of his elder son Titus might have been the earliest public event to be imprinted in his memory. Vespasian was at Aquae Cutiliae, a Sabine spa, when he succumbed – to a fever rather than to gout, Cassius Dio reports. In spite of which, according to Dio ‘there have been some who spread the story that Titus had poisoned his father at a banquet.’ One of these rumour-mongers, he adds, was none other than the Emperor Hadrian. When Hadrian made the charge is not stated and where Dio found out about it is not clear. One might assume that Hadrian was quoted to this effect by Marius Maximus. Hadrian might even have found occasion to refer to the story in his autobiography. But such a claim by Hadrian might have gone the rounds in senatorial circles for years and years. The boy Hadrian can hardly have heard the allegation in 79, but the odds are that it surfaced under Domitian, who is credited with other smears against his brother. The fact that Hadrian believed it and later repeated it is perhaps an indirect sign of his attitude to Domitian.10

A succession of striking events in Rome and Italy from 79 onwards must have made some impact on a child at Rome. It is enough merely to list them. The eruption of Vesuvius and the disappearance of Pompeii and Herculaneum in August 79 is an obvious enough sensation. More immediate would be the fire at Rome itself the following year, less disastrous and dramatic than the great fire under Nero in 64, but serious enough to consume the rebuilt temple of Jupiter on the Capitol destroyed in another blaze at the end of 69. Also very striking – even for a child too young to attend – would be the opening of the vast new Flavian amphitheatre (the ‘Colosseum’) by Titus in the summer of 80, with a hundred days of spectacles. Titus’ death the following September and the accession of his much younger brother Domitian was another landmark. Not much more than two years later Domitian would return from his brief participation in a northern war with the title ‘Germanicus’. The eight-year-old Hadrian probably watched the triumph early in 84. Whether he also registered discussion of a famous Roman victory in the far north, won by Julius Agricola against the Caledonians at the battle of the Graupian Mountain in September 83, can be guessed with rather less confidence. The great general returned to Rome quietly the next year and withdrew to private life. All the same, Agricola was granted the triumphal insignia, the only man so honoured under Domitian.11

In the course of the year 85 or at the latest in January 86 came the death of Hadrian’s father. Guardians were appointed for the boy, as he had not yet assumed the toga of manhood: his first cousin once removed, Trajan, by now in his early thirties, and another man from Italica, P. Acilius Attianus, a Roman knight, aged forty-five. Their principal task was to look after the inherited property, but Trajan may perhaps have played the part of a substitute parent. He was presumably by now married, his wife being Pompeia Plotina: she was also of colonial’ origin, from Nemausus (Nîmes) in Narbonensis. Plotina was probably only a few years older than Hadrian, and her relationship with him was very warm in later years. He would also become very fond of his second cousin Matidia, she too being not many years older than himself. She was the daughter of Trajan’s sister Marciana, and was probably married in the early 80s, at the age of about fourteen or fifteen, to a man called Mindius. She bore a daughter, named af...