- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Dionysos

About this book

Covering a wide range of issues which have been overlooked in the past, including mystery, cult and philosophy, Richard Seaford explores Dionysos – one of the most studied figures of the ancient Greek gods.

Popularly known as the god of wine and frenzied abandon, and an influential figure for theatre where drama originated as part of the cult of Dionysos, Seaford goes beyond the mundane and usual to explore the history and influence of this god as never before.

As a volume in the popular Gods and Heroes series, this is an indispensible introduction to the subject, and an excellent reference point for higher-level study.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

GeschichteSubtopic

AltertumKEY THEMES

2

NATURE

INTRODUCTION

For many centuries of European history Dionysos was thought of as the god of wine, or of the unrestrained joys of nature (as for instance in the Titian painting reproduced as Figure 7). But the unrestrained joys of nature are an urban vision. For most people in ancient societies life was a struggle to control nature. And so it was important to win the favour of what we call the powers of nature, what they imagined as deities. Prominent among such deities was Dionysos. To be sure, given his pervasive power, his activity was not confined to the vineyard. But just as the production of food is a precondition for all other human activities, so there is a sense in which Dionysos’ association with ‘nature’ is basic to the various activities to be described in this book, and so that is where we start.

WINE

In the thirteenth century BC economic records were written in Greek on tablets in a script known as Linear B. On three of these tablets, from Pylos in the western Peloponnese and from Chania in Crete, the name Dionysos appears for the first time, in the Chania tablet along with the name of Zeus. Although it has been argued that one of the Pylos tablets also provides evidence for Dionysos’ connection with wine, this is uncertain. But given that Greek viticulture was already important in this period, and that it was certainly associated with Dionysos from the seventh century BC throughout Graeco-Roman antiquity, it is likely that this association stretched back also into the relatively unknown centuries from the thirteenth to the seventh BC. Our first certain evidence of the association is in the oldest surviving Greek poetry. Dionysos is mentioned briefly in Homeric epic four times, of which two imply an association with wine: at Iliad 14.325 he is called a ‘joy for mortals’, and at Odyssey 24.74–6 he is the donor to Thetis of the golden amphora that is eventually to contain the bones of her son Achilles in unmixed wine and oil. The amphora was generally used for wine (e.g. Odyssey 2.290), as well as having here the association with death characteristic of Dionysos (Chapter 6). It is difficult to date these references: much of Homeric epic derives from the eighth century BC, but it probably did not take its final form before the sixth. Hesiod, who seems to have lived around 700 BC, speaks of wine as ‘gifts of Dionysos’ (Works and Days 614). The poet Archilochus, who was active in the middle of the seventh century BC, claims to know how to sing – with his mind ‘thunderbolted with wine’ – the song of Dionysos, the dithyramb (fragment 120).

In the sixth and fifth centuries the most abundant evidence for Dionysos as the god of wine is in Athenian vase-painting. Many of the vases were used to contain wine, and are accordingly often decorated with pictures of Dionysos and of his retinue of ‘silens’ or ‘satyrs’ – hedonistic males with some equine characteristics, fond of revelry, sex, music, and wine. The god frequently carries a drinking vessel, the satyrs are often engaged in the production (picking and treading grapes) and the transport of wine, sometimes in the presence of Dionysos, and the scenes are often decorated with vines.

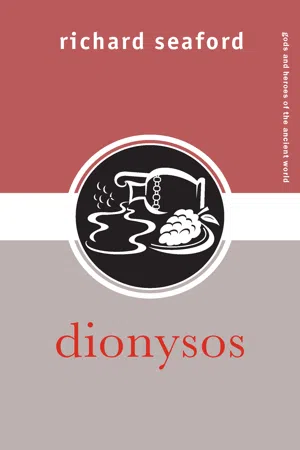

Of special interest is one of the very earliest (c. 570 BC) surviving pictures of Dionysos, by Sophilos (Figure 1) in his vase-painting of the wedding of Peleus and Thetis: Dionysos walks in a procession of deities towards the bridegroom Peleus, who is standing in front of his house, facing the procession, and holding a kantharos (drinking cup). Dionysos holds up in front of him a grape-vine, presumably as a gift for Peleus. A little later the same scene was painted by Kleitias (on the ‘François Vase’ in Florence): Dionysos again carries a grape-vine, but also carries on his shoulder an amphora (no doubt in this context a

Figure 1 Attic dinos painted by Sophilos.

Source: © Courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum.

wine-jar), and – despite moving rightwards in the procession – his mask-like face is turned to stare straight at the viewer.

On both vases Dionysos seems less civilised or more rustic than the other deities in the procession. In Sophilos’ painting he is barefoot and walking rather than in a chariot, in Kleitias’ he is barefoot and long-bearded. And whereas what he carries, the grape-vine, is taken directly from nature, the wine-cup carried by Peleus contains the grape-vine transformed by culture.

The festival called Anthesteria was celebrated in honour of Dionysos by many Ionian communities, although the details of its enactment are known almost entirely from Athens. Celebrated in late February, it centred on the opening and drinking of the wine produced in the previous autumn. In the autumn, at the time of the vintage and wine-pressing, the Athenians celebrated the Oschophoria, named after the bunches of grapes on branches carried in procession. The vintage was an event of joyful and seasonally determined communality as well as of economic significance, and the evidence for it being accompanied by Dionysiac celebration is found throughout antiquity. In the pastoral romance Daphnis and Chloe by Longus (c. AD 200), erotic desire at a vintage festival on Lesbos is said to be appropriate to ‘a festival of Dionysos and the birth of wine’ (2.2.1). The association of the vintage with Dionysos lasted – to judge by Christian condemnation (Chapter 9) – into the late seventh century AD.

THE ANTHESTERIA

I mention briefly here various aspects of the Anthesteria that are characteristic of Dionysiac cult generally, and will return to each of them in a subsequent chapter.

First, not even slaves or children were excluded from the wine-drinking. Wine is communally celebrated not only because its production is communal but also because its transformative effect may, in being enjoyed by all male members of the community, tend to remove barriers between them. It was Dionysos, according to the chorus of Euripides’ Bacchae (421–3), who ‘gave the pain-removing delight of wine equally to the wealthy man and to the lesser man’. Though in the paintings by Sophilos and Kleitias Dionysos seems less aristocratic than the other gods, the wine he brings is needed for the aristocratic wedding-feast. We will see that it was wine, administered by Dionysos, that reintegrated the artisan Hephaistos into the community of Olympian gods. In Daphnis and Chloe the owners of the country estate leave their town dwellings to join the rural workers in celebrating the vintage. To the communality inspired by Dionysos I will return in Chapter 3.

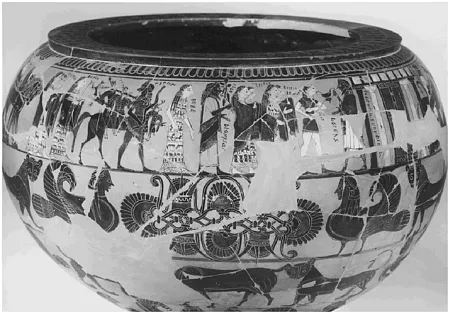

Second, at the Anthesteria it seems that Dionysos was escorted into the city in a cart shaped like a ship in a procession (depicted in vase-paintings). In the Homeric Hymn to Dionysos the god takes the form of a young man, is captured by pirates, and makes his epiphany (as a lion) on their ship, accompanied by miracles that include a spring of wine, the appearance of a vine with abundant grape-bunches along the top of the sail, and the transformation of the pirates into dolphins. A wonderful sixth-century BC vase-painting by Exekias depicts the scene (Figure 2). In the paintings of Dionysos in the ship-cart procession he is holding up a vine that stretches the length of the ship: this suggests that the procession commemorated the mythical epiphany. The arrival of Dionysos to public acclamation is also an epiphany (Chapter 4).

It was imagined that, perhaps at the conclusion of the procession, Dionysos was sexually united with the wife of the ‘king’ (in fact a magistrate) in the old royal house. This resembles the myth of Dionysos arriving at the house of Oeneus (king of Calydon in Aetolia) and having sex with his wife. Oeneus, whose name means ‘wine man’, tactfully withdrew, and was rewarded with the gift of the vine. This symbolic limitation on the autonomy of the royal household benefits – as does the opening of the new wine – the community as a whole.

Figure 2 Attic kylix painted by Exekias.

Source: Munich, Staatl. Antikenslg. & Glyptothek. Photo reproduced by permission of akg-images, London/Erich Lessing.

Dionysos may make his epiphany at his festival not only by entering the city but also as a miraculous spring of wine, with which he may be identified (Chapter 5). According to Pausanias (second century AD) the people of Elis assert that Dionysos comes to their festival: three pots are placed empty inside a temple of Dionysos, the doors are sealed, and the next day the pots are found filled with wine (6.26.1–2). The people of Andros, adds Pausanias, say that at their festival of Dionysos wine flows of its own accord from the temple. In a myth about the origin of a festival of Dionysos at Tyre the newly invented wine is described by the god as a ‘spring’ (Chapter 9). In the classical period Greek women were normally discouraged from drinking wine. But in Euripides’ Bacchae (707; cf. 142) Dionysos creates from the earth a spring of wine for his female followers (‘maenads’). There are magic vines that produce mature grapes in a single day (Sophokles fragment 253), and Apulian vase-paintings depict wine flowing directly from grapes (Chapters 6 and 7).

Third, despite its communality the Anthesteria contained secret rituals, performed by a band of women, that included sacrifice, an oath, and the sexual union between Dionysos and the wife of the ‘king’. These female rituals have been connected, albeit controversially, with a series of fifth-century BC Athenian vase-paintings that show women performing ritual around an image of Dionysos (e.g. Figure 3) and sometimes ladling wine from a large container into cups as an offering to the god. A fragmentary text discovered on papyrus associates the invention of wine with Dionysiac mystic initiation (TrGF II 646a). To the performance of secret Dionysiac ritual at the heart of a communal festival, and to the use of wine in mystery-cult, we will return in Chapter 5.

Fourth, the Anthesteria was not the festival of unmitigated joy that we might expect of a wine festival. Several elements of it embody death or pollution. For instance, a myth associated with the festival was that Dionysos first revealed the vine and wine-making to an Attic peasant called Ikarios, who shared the wine with his neighbours. But on drinking the wine they thought themselves poisoned, and killed Ikarios. His daughter Erigone consequently hanged herself, and this hanging was commemorated in the swinging of Athenian girls at the Anthesteria. In the Odyssey we find not only the use of wine in the

Figure 3 Attic kylix painted by Makron.

Source: Berlin, Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. Reproduced by permission of bpk Berlin, photo by Ingrid Geske-Heiden.

burial of Achilles (see above, p. 16), but also – and more relevantly to the Ikarios story – instances of the power of wine to engender death (11.61) and violence (21.295–301). According to Plutarch (Moralia 655) the Athenians at the Anthesteria used t...

Table of contents

- Gods and Heroes of the Ancient World

- CONTENTS

- SERIES FOREWORD

- ILLUSTRATIONS

- WHY DIONYSOS?

- KEY THEMES

- DIONYSOS AFTERWARDS

- FURTHER READING

- WORKS CITED

- INDEX

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Dionysos by Richard Seaford in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Geschichte & Altertum. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.