![]()

1 The children

It was my second week of working with children from the original Year 5 set. Within the set, the third of three sets, they were grouped by perceived ability into five groups. The teacher asked me to sit with one of these groups and to give particular help to one girl, Julie. He added that I would notice the difference between her and the child sitting the other side of me, Sean.

Introduction

The aim of this chapter is to introduce some of the children I worked alongside and to give a feel for their approach to mathematics. Subsequent chapters deal with particular types of mathematical task and most of the children introduced here are mentioned again in later chapters. I was often asked by the teachers to work with certain children and this chapter starts by introducing the group I worked with first. Some children from other classes are also introduced in order to indicate the types of children present. Before the children are introduced, the background reading section deals with some existing work on children in bottom sets as well as tackling the issue of labels and terminology. The chapter concludes that children in bottom sets can be different in many ways. It is difficult to make general statements that apply to all these children. Even to say that they are low attainers in mathematics is problematic for some children, who do not appear to have given a clear indication of their attainment.

Background

Who is in the bottom sets?

All forms of ability grouping carry the danger that certain groups of children might be over-represented in lower sets or streams. This issue is considered in a review of research by Sukhnandan and Lee (1998). They point to work which suggests that such sets or streams contain a disproportionately large number of children from working-class and ethnic minority backgrounds. Gender and season of birth are also said to influence placement of pupils. A further issue is whether children with challenging behaviour are sometimes put in bottom sets for this reason rather than on academic grounds. Research has suggested that both teachers and pupils believe this sometimes happens (Ireson and Hallam 2001). A further issue related to the composition of all sets is how similar the children in any set are likely to be. Some writers suggest that teachers commonly believe that children in given sets will all be very similar, but this is often far from the case (Boaler 1997).

Labels

This study is concerned with children who are in bottom sets, regardless of their reason for being there. It is difficult to talk about them as groups or to draw on relevant background reading without addressing the issue of labels. In some cases the teachers referred to these children as ‘lower ability’. Most recent literature talks about ‘low attainers’ or ‘low-attaining students’, resisting the implication that success, or otherwise, at mathematics is inborn and unchangeable. At the time of the study, English schools were required to keep a register of pupils considered to have special educational needs. As Robbins (2000) suggests, there is likely to be considerable overlap between this group and those regarded as low attainers in mathematics. He goes on to say that the term ‘special educational needs’ is very general and can be thought to have limited value. A large-scale survey of the extent and type of special needs in English primary schools was carried out by Croll and Moses (2000). They found that the largest category consisted of pupils considered to have learning difficulties, followed by a group with emotional and behavioural difficulties. A much smaller group were identified as having health, sensory and physical difficulties. However, they also express reservations about the term ‘special educational needs’, suggesting that it is very difficult to define a point at which educational needs become special.

Low attainers in mathematics

Work on low attainers in mathematics has tried to both describe and explain low attainment. Descriptions of low-attaining pupils have tended to emphasise their diversity. Similarly, attempts at explanations have implied a breadth of possibilities. For example, Haylock (1991) talks about broad range and great variety in relation to children with low attainment in mathematics. He goes on to present case studies of individuals who show a complex combination of difficulties in understanding and engagement with the work. In an older study, Denvir et al. (1982) also draw on examples to illustrate the diversity of low attainers. They go on to assert that these children will not form a homogeneous group. In discussing reasons for low attainment, they suggest a range of possibilities. Some of these, they say, are beyond the control of the school, whereas others may be partly or directly under the school’s control.

Evidence of attainment

The use of the phrase ‘low attainers’, while carrying fewer assumptions than ‘low ability’, is still problematic. It assumes that children have been offered opportunities to demonstrate their attainment and have done so. Problems are likely to arise if demonstration of attainment has been blocked by non-mathematical factors. For example, children with reading and writing difficulties may not show evidence of attainment on written tests. It is also possible that some children will not show evidence of attainment due to motivation or behaviour problems. Some groups of children present particular challenges as far as assessing attainment is concerned. Children who speak little or no English are unlikely to demonstrate their mathematical attainment if tasks are presented using spoken or written English. It is acknowledged by Hall (2001) that it is hard to assess the needs of bilingual pupils who may have special educational needs. She draws on the work of Wright (1991) in pointing out two possible errors. The first of these, ‘false positive’, involves diagnosing a learning difficulty when none is present. The other error, ‘false negative’, consists of failing to diagnose a learning difficulty. Thus, although it is crucial not to consider all bilingual children as having learning difficulties, it is important to acknowledge that some might.

There may also be some children who have not been provided with the opportunity to show their attainment if they arrive at a school after assessment has taken place and without evidence of prior attainment. The issue of mobility in schools has been the subject of recent concern (Dobson and Henthorne 1999). A study by Whitburn (2001) found lower levels of attainment in mathematics among mobile pupils as compared to stable pupils within the same school. A study looking at the effects of pupil mobility and what schools can do to mitigate these effects (OFSTED 2002) drew attention to the problems of assessing attainment. They acknowledged the difficulties for schools with high levels of mobility in induction and assessment. They also pointed out the impact of inadequate assessment on pupils. Some pupils interviewed for the study complained either that they had done work before or that they did not know what was going on. The study acknowledged the complexity of the relationship between attainment and mobility. They say this is partly because pupil mobility often occurs alongside other factors such as disrupted family life.

Contemporary advice

My research was carried out at a time when a large-scale national initiative, known as the National Numeracy Strategy, was being introduced in English primary schools. Documentation associated with the strategy (DfEE 1999a) offers advice to teachers about pupils with particular needs, including special educational needs. The main message is that as many children as possible should be included in the daily mathematics lesson. There is a push towards including all or most pupils rather than planning individually or over-differentiating. Teachers are encouraged to adopt strategies to enable all pupils to be included. These include minimising written instructions and making use of number aids. The section on special educational needs points out that children who have problems with mathematics often but not always also have literacy problems. The needs of pupils with emotional or behavioural difficulties are also briefly mentioned. Further guidance was subsequently issued to assist teachers and classroom assistants working with pupils with specific needs (DfES 2001). This document is divided into five sections, each of which offers guidance for working with pupils with particular needs. The needs are: (1) dyslexia or discalculia; (2) autistic spectrum disorders; (3) speech and language difficulties; (4) hearing impairments; and (5) visual impairments.

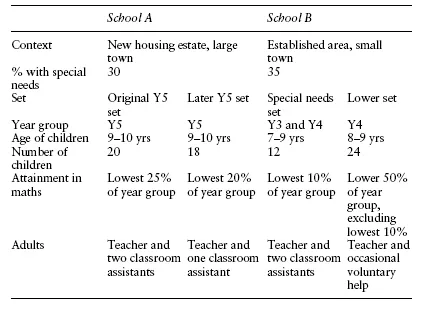

In the classrooms

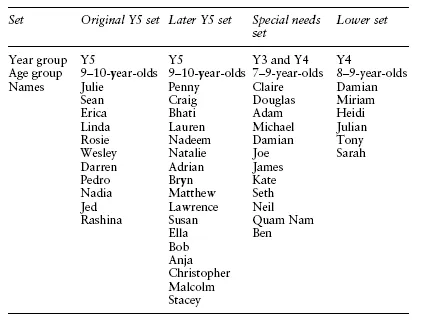

There was some variation between the four sets of children I worked with in terms of the perceived needs of the children in the set. At one extreme was a mixed-age class of 7–9-year-olds, which I shall call the special needs set. The children in this set represented approximately the lowest 10 per cent of the attainment range in mathematics and all were considered to have special needs as far as mathematics was concerned. At the other extreme was a set of 8- and 9-year-old children in the same school, which I will refer to as the lower set. This set contained approximately the lower 50 per cent of the attainment range but with the lowest 10 per cent removed. However, because the school had approximately 35 per cent of children considered to have special needs, there were many such children in this set. When working in the lower set, I almost always worked with the small group of children considered to have the greatest difficulty. The other two sets of children both consisted of 9- and 10-year-olds. They were in the same school but I worked with them in different years. One set, which I will call the original Year 5 set, consisted of approximately the lowest 25 per cent of the attainment range in mathematics. For the later Year 5 set, this changed to about 20 per cent (see Table 1.1). Additional information is given in Table 1.2, including the ages and names of children. Only the names of children mentioned in this book are included and all the names used are pseudonyms.

The information in Tables 1.1 and 1.2 gives some idea of the formal position and hopefully will help those working in other schools to get a picture of how the situations I worked in compare to their own. Nevertheless, this information says very little about what the children were like and what kinds of difficulties they experienced. In reality, there were great differences in the children and in their approach to mathematics. The rest of this section is spent introducing some of the children in order to illustrate the variety.

Table 1.1 The schools and the sets

Table 1.2 The children taking part in the study

The table in the corner

My first term of fieldwork was with a Year 5 set. At the teacher’s request, I worked with a group of children who sat at the table in a corner of the room. The children in the room were in the bottom of three mathematics sets and within the set the teacher had grouped them according to ‘ability’. The group I worked with were the middle of five groups within the set. There were five children in the group. The teacher had particularly requested that I work with one child, Julie:

Julie

It was soon clear why the teacher felt Julie needed support. She found some aspects of calculation quite difficult. For example, she worked slowly through a sheet about multiplying by 4 and had problems with calculations in the context of shopping, being confused by the mixture of addition and subtraction. She also had some difficulty in writing difference as a subtraction when the smaller number was given first. Julie persevered with formal methods of calculation taught by the teacher. She seemed to favour methods which dealt with numbers digit by digit rather than holistically. Despite Julie’s success with formal written tasks, I continued to notice difficulties with aspects of number. For example, one week I worked with Julie on an activity about giving change for £1. At one point Julie was counting on from 88p to £1. She counted to 89 and said she didn’t know which number came next. I encouraged her to try and she suggested first 70, then 80.

I soon noticed the difference between Julie’s approach to mathematics and that of Sean, who sat on the other side of me. The teacher’s comments recorded at the start of this chapter show that he was aware of this difference too:

Sean

In the first two weeks I noticed Sean’s confidence in mental calculation. He was one of the fastest in the class at completing the sheet about multiplying by 4. On one occasion he fell behind the rest of the table because he lost his pencil. On tasks involving column subtraction, I noticed that Sean’s work did not include crossing out of digits, suggesting he was not using the decomposition method advocated by the teacher. One task which Sean had problems with involved drawing a chart. The children had a chart on a piece of paper but had to copy this into their maths books. Sean did make an attempt to draw a chart but gave up when the columns turned out the wrong size. Sean sometimes made a point of saying that he found the work easy, and he seemed reluctant to seek or accept help. However, over the weeks he did start chatting to me, especially when I first arrived in the room before the lesson started. Sometimes during activities, he made comments in a whisper. These may or may not have been aimed at me but he did not seem to require a response. These comments or whispers became a regular part of mathematics lessons.

Although I continued to sit between Julie and Sean, I slowly got to know the other children at the table. Erica, who sat opposite me, was new to the school that term, having just arrived in the country. She was known by an English name but was of Chinese appearance and we later discovered that she had recently attended school in Singapore:

Erica

Erica spoke almost no English when she arrived, though it was encouraging to see how quickly she made progress with the language. However, she could do some of the mathematics, though this depended how it was presented. Worksheets involving computation only were unproblematic for Erica. She completed these sheets with a speed that particularly impressed Sean, who drew my attention to it. For example, she had no difficulties with a sheet involving subtraction of four-digit numbers. She did not cross the digits out but worked from right to left and completed calculations quickly and accurately. On the other hand, she was greatly slowed down by complex instructions, either spoken or written. One week the children were given a sheet headed ‘sale’, which started with a picture of a shop window full of priced items followed by word problems. Erica was at a loss to cope with the sheet until Rosie, the girl next to her, intervened. ‘It’s easy,’ Rosie explained. ‘If it’s got the word “cost” in it, you add the numbers up. If it’s got the word “left”, then it’s a take-away.’

The two other children on the table were called Rosie and Linda. Rosie sat between Erica and Sean. She seemed to cope reasonably well with the mathematics presented, though I never got to know her in any depth. After a few weeks, her attendance became intermittent. Around Christmas she disappeared altogether, although it was not clear when she officially left the school. The fifth child on the table was Linda, who sat on the other side of Erica:

Linda

Over the weeks, Linda started requesting my help on occasions, especially when worksheets had just been given out. She showed some anxiety about whether she knew what to do and whether she was doing what the teacher wanted. Once, when the teacher used the expression ‘find the sum’, Linda turned to me and said ‘Miss, is it an add or a take-away?’ She also expressed anxiety about non-mathematical aspects of the tasks such as whether they should work in pen or pencil and which way round they should have the paper.

After a term working on the corner table, I was able to reflect on the different mathematical needs and strengths of the five children. They had already been set by ability and were ability grouped within the set. It might seem reasonable to assume that such an arrangement should lead to a group of children who are similar mathematically. In fact, this was far from the case. Julie certainly had problems with mathematics, as did Linda. Sean’s problems seemed to be of a different type. Erica could do mathematics presented in certain ways but was hampered by instructions given in English. Rosie was hampered mostly, it seemed, by intermittent attendance. Reflecting on the strengths and weaknesses of these five children led me to think about who ended up in bottom sets and why. In particular, there is a question about whether all children placed in bottom sets can reasonably be described as low attainers in mathematics.

The other children

As my fieldwork continued, I met other children who, like Sean, seemed adept at mental calculation but performed less well at written tasks. There were also others like Julie, who seemed to prefer formal written work to mental calculation. Three of the four sets I worked in contained children for whom English was not their first language, some, like Erica, in the very early stages of learning it. Children who were low in confidence, like Linda, were to be found in all four sets. The first school I worked in had relatively high pupil mobility. It contained sudden leavers like Rosie and children who appeared part-way through the year like Penny, who is introduced below. Another midyear arrival in the same set as Penny was Craig, who had been moved down from a higher set:

Penny

Penny joined the school just before Christmas, having recently attended other schools in the area at which she was unhappy. Watching Penny over the next few months led me to believe she was still ...