![]()

Chapter 1

Detectives hunting for missing eight-year-old Sarah Payne today found the body of a young girl north of Littlehampton. The body was found near the grounds of Brinsbury agricultural college, in Pulborough, West Sussex, about ten miles from the area where Sarah disappeared on July 1.

Guardian, Monday 17 July 2000

Police confirmed yesterday that the body of a girl found in a field in West Sussex was that of eight-year-old Sarah Payne … Detectives said the body was naked but would not say if there was evidence that the girl, who had been missing since the start of the month, had been sexually assaulted.

Guardian, Wednesday 19 July 2000

There must be no hiding place for the evil perverts who prey on our children. For too long the nation has endured the pain of seeing innocents such as Sarah Payne snatched from streets to become victims of paedophiles.

News of the World,

Sunday 23 July 2000

The people of Britain have been given their chance to speak on the subject of child sex offenders in a significant MORI poll commissioned by the News of the World. Its conclusions below show a gulf between us and our lawmakers. It must not be ignored by our politicians, our police or our courts. The British public has voiced huge support for the News of the World’s proposals to identify all paedophiles. In an eye-opening public opinion poll: 88 per cent of those questioned say parents should be told if a child sex offender is living in their area; 75 per cent say perverts jailed for life for sex crimes against children should never go free; 82 per cent believe paedophiles should be chemically castrated – their sex drives suppressed by drugs.

Charles Begley, News of the World,

Sunday 23 July 2000

Today, in a groundbreaking edition of the Irish News of the World, we begin the biggest public record of child sex offenders ever seen. We do so in memory of Sarah Payne, whose murder broke so many hearts. There are 110,000 proven paedophiles roaming free in the UK, one for every square mile of the country. Today we begin naming them. Week in, week out, we will add to the list of shame.

Terenia Taras and Paul McMullan, Irish News of the World,

Sunday 23 July 2000

An uneasy truce was declared yesterday by seething protesters fighting to drive alleged paedophiles off a troubled council estate. Demo leaders announced they were suspending their campaign for one day of talks with local officials. The move followed seven nights of violent protests on the Paulsgrove Estate, Portsmouth, Hants. Five families have fled as mobs of up to 300 people fire-bombed cars and stoned houses of suspected perverts. Action group Peaceful Protesters of Paulsgrove claim to have a list of 20 paedophiles on the estate and say they will be targeted until they leave. However there are only two known sex offenders on the estate and police say four families who fled had ‘nothing to do’ with child sex.

Stewart Whittingham, News of the World,

Friday 11 August 2000

Violence has also flared in Plymouth, a man was chased by a mob in Whitley, Berkshire, and two men accused of child sex offences have committed suicide. Police said a millionaire businessman … arrested over child sex charges, had been found on Sunday night shot dead at his Kent home … what they’ve [News of the World] created is an atmosphere of fear among members of the public, among parents and among sex offenders …

Vikram Dodd, Guardian, Thursday 10 August 2000

These extracts from British newspaper clippings highlight a train of events which was sparked off on 1 July 2000 by the disappearance of an 8-year-old girl, Sarah Payne. On 17 July, a girl’s body was found, and two days later it was confirmed to be that of Sarah. The nation was undoubtedly horrified, and moved by the dignified presence of Sarah’s family in the media. Less than a week later, the News of the World – a popular national tabloid newspaper – launched a controversial campaign to ‘name and shame’ all the known paedophiles in Britain. By 4 August 2000, there was public unrest, most notably in an estate near Portsmouth, where protests to move paedophiles away from the locality erupted in violence for a period of a week. The ‘name and shame’ campaign was dropped by the News of the World in favour of a more muted lobbying for ‘Sarah’s Law’, which focused on empowering parents and victims, and improving prevention of sex offences.

This was a highly emotional three weeks for all concerned – the public, the media and sex offenders themselves. Yet, for all the drama and controversy, this example raises very meaningful questions about the nature of the risk posed by sex offenders, and the most effective means of managing that risk in the community. Such questions might include

• Is the risk on the streets or at home?

• Are women as unsafe as children?

• Does action arising from sexually motivated child murders help us in managing other types of sex offender?

• Are sex offenders likely to escalate in their behaviour if not stopped?

• Is there any form of treatment which can be guaranteed to be effective?

• Can we differentiate between those offenders who will and those who will not reoffend?

• What role can the community play in the management of sex offenders?

• Is current legislation and statutory practice ineffective?

• Does community notification always lead to vigilante behaviour?

Clearly, there are not answers to all these questions, and those answers that there are may be equivocal. Nevertheless, the following pages attempt to provide the reader with a range of practical and evidence-based information to enable them to gain confidence in their risk management practice with sex offenders.

The scope of the book

This book is aimed at a range of practitioners working in a range of agencies. It is assumed that there will be a variety of skills and knowledge bases among readers, and this is taken into account. However, so much has been written and spoken about sexual offenders that it is important to set some boundaries to the scope of the book, in order to retain its focus. The decision was made to focus on contact sexual offences, the adult men who commit such offences, and in particular those individuals who pose the highest risk of sexual reoffending. This is a pragmatic approach, reflecting public concern with behaviour which is problematic in terms of its apparent frequency and its likely impact on others. Although much of the material is relevant to specialist groups of offenders, there are inevitable omissions: learning disability is briefly discussed in Chapters 3 and 6, but is not extensively reviewed in terms of community management approaches. Non-contact sexual behaviours – indecent exposure and pornography use – are discussed in terms of their potential contribution to risk assessment in contact sex offenders; however, current public interest in internet pornography offences as a subject in its own right is not reflected in this book and the reader may wish to seek out specialist material on this relatively new subject (see Cooper 2002; Taylor & Quayle 2003).

However, work on adolescent sex offenders and, to a lesser extent, female sex offenders, has become more mainstream, and these two groups are discussed in greater detail. Common sense would suggest that there is some overlap between the approach to adult male sex offenders and other groups, but the evidence base is not yet sufficiently sophisticated to support this premise. Some introductory comments about adolescent and female offenders are set out below.

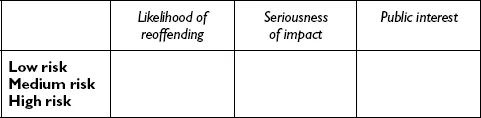

A further restriction of the book is the area of risk upon which the primary focus rests; that is, there are many possible forms of risk. Whatever the limitations of such an approach, this book has largely restricted itself to consideration of risk to others, with a particular emphasis on the likelihood of sexual reoffending. Victim impact – the subject of much research and commentary – is not discussed in any detail. Table 1.1 lays out a simple framework for risk assessment which suggests that key risk areas include the likelihood of reoffending, the seriousness of victim impact and public interest. This latter area includes professional and institutional risk when failures in the community occur. Clearly, an offender may lie at different risk levels in terms of offending probability, victim impact and professional/institutional/public consequences.

Table 1.1 Risk table

In terms of the use of terminology in this book, a sexual offender refers to an individual who has engaged in illegal sexual behaviour, whether or not he or she has been convicted. An index offence relates to the most recent (sexual) conviction and sexual reoffending – perpetrating another illegal sexual act (whether caught or not) – is labelled sexual reconviction or sexual recidivism when a further conviction is obtained. However, when a study makes clear that arrests and charges are considered as well as convictions, sexual recidivism is used. Offenders against children (under the age of 16) are called child molesters, and offenders against adults – women victims unless specified – are called rapists. This is admittedly something of a shorthand, which does not relate to the conviction but to the age of the victim. Unless otherwise stated, the use of the male prefix reflects the emphasis on male sex offenders. If any of the research cited in the book differs markedly in its use of terminology, this is made clear at the time.

The extent of the problem

Determining the extent of the problem is fraught with difficulties. Randomised retrospective surveys of the general adult population estimate that 12 per cent of females and 8 per cent of males have experienced unwanted contact before the age of 16 (Baker & Duncan 1985). However, figures vary according to the style of survey (whether or not non-contact behaviours are included) and the numbers of victims are unlikely to reflect the number of perpetrators, some of whom will have engaged in prolific illegal sexual activity (Abel, Becker, Mittelman, Cunningham-Rathner, Rouleau, & Murphy 1987). Determining the prevalence of sexual offenders who have never been convicted is particularly problematic. Social services child protection teams manage families where children have been identified as being at serious risk of sexual abuse, although the majority of alleged perpetrators have not been prosecuted. For example, McClurg and Craissati (1999) found that between 0 and 8 per cent of these alleged perpetrators in two London boroughs were convicted as a result of the allegations.

In terms of adult victims, the British Crime Survey (BCS) (Myhill & Allen 2002) found that 0.4 per cent of women aged 16 to 59 in England and Wales said they had been raped in the year preceding the 2000 BCS, which was estimated at 61,000 victims. Around 5 per cent of women said they had been raped since the age of 16, while 10 per cent of women said they had experienced some form of sexual victimisation in that time (including rape). Approximately 20 per cent of sexual victimisation incidents in the preceding year came to the attention of the police (an estimated 12,000).

However, if we then turn to official crime statistics in the year 2000/1 (Simmons et al. 2002), there were 41,425 recorded sexual offences, of which 9,743 were for rape (9,008 of which were against a female), and 21,765 were for indecent assault on a female. Although offence categories do not necessarily allow for the differentiation between child and adult victims, these figures would suggest that it is reasonable to presume that only one fifth of sexual offences are actually reported to the police.

With regard to the offenders, in 1995 in England and Wales, 4,600 men and 100 women were sentenced by the courts for indictable sexual offences and a further 2,250 were cautioned. Of these, 2,554 convictions were for sexual offences against children (aged less than 16), 19 of whom were female offenders. By the age of 40, Marshall (1997) estimated that 1.1 per cent of men born in 1953 had a conviction for a serious sexual offence, 0.7 per cent of whom clearly had a child victim (0.6 per cent a girl victim and 0.1 per cent a boy victim). Estimating the population of sex offenders, 260,000 men had a conviction for any sexual offence, of which 165,000 had a conviction for a serious sexual offence, and 110,000 had a conviction for an offence against a child.

Official recording figures of crime are very different to conviction figures. There are many intervening factors, not least the possibility that no crime has been committed, or that no suspect is found or charged. Even when a conviction is obtained, the type of conviction may not reflect the extent or nature of the sexually abusive behaviour. Some homicide, harassment and false imprisonment offences may contain a predominantly sexual element. It is well understood that the criminal justice process also distorts the picture: offenders may only be convicted of ‘specimen’ charges when abuse has occurred over a lengthy period or with a number of victims; charges are likely to be dropped or reduced in order to secure a conviction or avoid a trial. A study of convicted child molesters in South East London (Craissati 1994) showed that charges were more than twice as likely to be dropped when child victims were under the age of 10; 47 per cent of initial vaginal and anal rape charges were dropped/reduced to indecent assault before trial. The criminal justice response to allegations of rape is clearly described in Harris and Grace’s (1999) interesting study, and it is worth examining their findings in more detail. They followed up all 483 cases initially recorded as rape in 1996 and compared their findings to a similar study in 1985. They found the following:

• Stranger rapes dropped from 30 per cent in 1985 to 12 per cent in 1996, while the number of recorded rape offences increased more than threefold – thus the number of stranger rapes has remained similar; in 66 per cent of crimed stranger cases, no suspect was caught despite advances in forensic science. Once detected, stranger attacks were the most likely to be crimed, but the low detection rate meant that they were the least likely to be prosecuted.

• Although only 5 per cent of complainants were aged over 45, they were the most likely to have reported being raped by a stranger; just over one quarter of complainants were aged less than 16 and 58 per cent of the total were aged 16 to 35.

• In 82 per cent of cases, there was some degree of consensual contact immediately prior to the attack (compared with 37 per cent of cases in 1985).

• Cases where there was no evidence of any violence, or the threat of violence, towards the complainant were more likely to be no-crimed, the most common reason being retraction by the complainant (36 per cent of 106 no-crimed cases). It was felt that sometimes withdrawal happened because the complainant was reunited with the suspect, although emotional and financial dependence was felt to be a common reason. Although a quarter of cases were no-crimed, this was much lower than in the previous study and the main reason was a police decision that the complaint was false or malicious (43 per cent).

• Cases involving particularly young complainants (<12) or older complainants (>45) were those most likely to be proceeded with by the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS), and 88 per cent of cases reaching the Crown Court involving complainants <13 led to a conviction.

• A quarter of the original sample of cases was discontinued and only a quarter reached Crown Cour...