1

TOWARD A THEORY OF CULTURE AND MISE EN SCÈNE

The object of this study is the crossroads of cultures in contemporary theatre practice. This crossroads, where foreign cultures, unfamiliar discourses and the myriad artistic effects of estrangement are jumbled together, is hard to define but it could assert itself, in years to come, as that of a theatre of culture(s). The moment is both favorable and difficult. Never before has the western stage contemplated and manipulated the various cultures of the world to such a degree, but never before has it been at such a loss as to what to make of their inexhaustible babble, their explosive mix, the inextricable collage of their languages. Mise en scène in the theatre is today perhaps the last refuge and the most rigorous laboratory for this mix: it examines every cultural representation, exposing each one to the eye and the ear, and displaying and appropriating it through the mediation of stage and auditorium. Access to this exceptional laboratory remains difficult, however, as much because of the artists, who do not like to talk too much about their creations, as because of the spectators, disarmed face to face with a phenomenon as complex and inexpressible as intercultural exchange. Does this difficulty spring from a purely aesthetic and consumerist vision of cultures, which thinks itself capable of dispensing with both socioeconomic and anthropological theory, or which would like to play anthropology against semiotics and sociology?

A SATURATED THEORY

When one seeks humanity, one seeks oneself. Every theory is something of a self-portrait.

André Leroi-Gourhan

Theory has a lot to put up with. It is reproached on the one hand for its complexity, on the other for its partiality. In our desire to understand theatre at the crossroads of culture, we certainly risk losing its substance, displacing theatre from one world to another, forgetting it along the way, and losing the means of observing all the maneuvers that accompany such a transfer and appropriation.

Any theory which would mark these cultural slippages suffers the same vertiginous displacement. The model of intertextuality, derived from structuralism and semiotics, yields to that of interculturalism. It is no longer enough to describe the relationships between texts (or even between performances) to grasp their internal functioning; it is also necessary to understand their inscription within contexts and cultures and to appreciate the cultural production that stems from these unexpected transfers. The term interculturalism, rather than multiculturalism or transculturalism, seems appropriate to the task of grasping the dialectic of exchanges of civilities between cultures.1

Confronted with intercultural exchange, contemporary theatre practice —from Artaud to Wilson, from Brook to Barba, from Heiner Müller to Ariane Mnouchkine—goes on the attack: it confronts and examines traditions, styles of performance and cultures which would never have encountered one another without this sudden need to fill a vacuum. And theory, as a docile servant of practice, no longer knows which way to turn: descriptive and sterile semiotics will no longer suffice, sociologism has been sent back to the drawing board, anthropology is seized on in all its forms—physical, economic, political, philosophical and cultural— though the nature of their relationships is unclear. But the most difficult link to establish is that between the sociosemiotic model and the anthropological approach. This link is all the more imperative as avantgarde theatre production attempts to get beyond the historicist model by way of a confrontation between the most diverse cultures, and (not without a certain risk of lapsing into folklore) to return to ritual, to myth and to anthropology as an integrating model of all experience (Barba, Grotowski, Brook, Schechner).

This keeps us within the scope of a semiology. Semiology has established itself as a discipline for the analysis of dramatic texts and stage performances. We are now beyond the quarrel between a semiology of text and a semiology of performance. Each has developed its own analytical tools and we no longer attempt to analyse a performance on the basis of a pre-existing dramatic text. However, the notion of a performance text (testo spettacolare, in the Italian terminology of de Marinis (1987:100)) is still frowned on by earlier semioticians such as Kowzan (1988:180) or even Elam (1989:4) and by cultural anthropologists (Halstrup 1990). This seems mainly a question of terminology because we certainly need a notion of texture, i.e. of a codified, readable artifact, be it a performance or the cultural models inscribed in it.

What is at stake is something quite different. It is the possibility of a universal, precise performance analysis and of an adequate notation system. It would seem that not only is notation never satisfying but that analysis can only ever be tentative and partial. If we accept these serious limitations, if we give up the hope of reconstructing the totality of a performance, then we can at least understand a few basic principles of the mise en scène: its main options, the acting choices, the organization of space and time. This may seem a rather poor analytic result, if we expect, as before, a precise and complete description of the performance. But, on the other hand, we should also question the aim of a precise and exhaustive semiotic description, if such a project arouses no interest. As Keir Elam puts it, ‘the more successful and rigorous we are in doing justice to the object, the less interest we seem to arouse within both the theatrical and the academic communities’ (1989:6). For this reason, Elam proposes a shift from theoretical to empirical semiotics: ‘a semiotics of theatre as empirical rather than theoretical object may yet be possible’ (1989: 11). It is certainly true that we should consider ‘reshaping’ the semiology of theatre by checking its theoretical hypotheses and results with the practical work of the actor, dramaturge and director (Pavis 1985). But it would be naïve to think that one will solve the problems of theory just by describing the process of production. It is not enough to follow carefully the preparations for the performance, to be among the actors, directors, musicians, as we are during the International School of Theatre Anthropology (ISTA). We also, and first and foremost, need theoretical tools in order to analyse the operations involved. One has to be able to help a ‘genuine’ audience understand the meaning of the production (and the production of meaning). How can the production be described and interpreted from the point of a single spectator receiving the production as an aesthetic object? Instead of looking for further refinement of western performance analysis, we can institute another approach, the study of intercultural theatre, in the hope that it will produce a new way of understanding theatre practice and will thus contribute to promoting a new methodology of performance analysis. In order to encompass this overflow of experiences, the theoretician needs a model with the patience and attention to minute detail of the hourglass.

AN HOURGLASS READY FOR EVERYTHING

We count the minutes we have left to live, and we shake our hourglass to hasten it along.

Alfred de Vigny

‘An hourglass? Dear Alfred, what is an hourglass?’ ask the younger generation with their quartz watches.

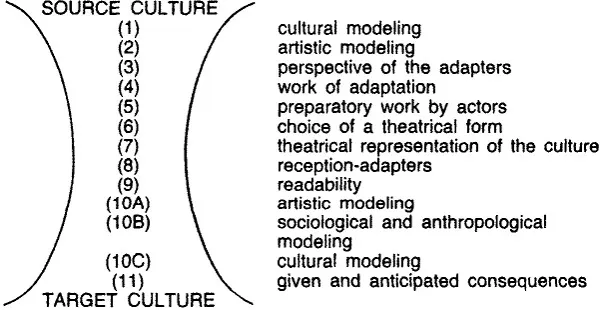

It is a strange object, reminiscent of a funnel and a mill (see Fig. 1.1 ). In the upper bowl is the foreign culture, the source culture, which is more or less codified and solidified in diverse anthropological, sociocultural or artistic modelizations. In order to reach us, this culture must pass through a narrow neck. If the grains of culture or their conglomerate are sufficiently fine, they will flow through without any trouble, however slowly, into the lower bowl, that of the target culture, from which point we observe this slow flow; The grains will rearrange themselves in a way which appears random, but which is partly regulated by their passage through some dozen filters put in place by the target culture and the observer.2

Figure 1.1 The hourglass of cultures

The hourglass presents two risks. If it is only a mill, it will blend the source culture, destroy its every specificity and drop into the lower bowl an inert and deformed substance which will have lost its original modeling without being molded into that of the target culture. If it is only a funnel, it will indiscriminately absorb the initial substance without reshaping it through the series of filters or leaving any trace of the original matter.

This book is devoted to the study of this hourglass and the filters interposed between ‘our’ culture and that of others, to these accommodating obstacles which check and fix the grains of culture and reconstitute sedimentary beds, themselves aspects and layers of culture. The better to show the relativity of the notion of culture and the complicated relationship that we have with it, we will focus here on the intercultural transfer between source and target culture. We will investigate how a target culture analyses and appropriates a foreign culture and how this appropriation is accompanied by a series of theatrical operations.

This appropriation of the other culture is never definitive, however. It is turned upside-down as soon as the users of a foreign culture ask themselves how they can communicate their own culture to another target culture. The hourglass is designed to be turned upside-down, to question once again every sedimentation, to flow indefinitely from one culture to the other.

What theory is, so to speak, contained in the hourglass? It has become almost impossible to represent other than in the metaphoric form of an hourglass. It includes a semiotic model of the production and reception of the performance (Pavis 1985) in which one can particularly study the reception of a performance and the transfer from one culture to the other.

Can the most complex case of theatre production, i.e. interculturalism, be of any use for the development and déblocage of the current theory of performance? It certainly forces the analyst to reconsider his own cultural parameters and his viewing habits, to accept elements he3 does not fully understand, to complement and activate the mise en scène. Barba’s practice (at the ISTA), his trial-and-error method, his search for a resistance, his confrontation, with a puzzle-like use of bricolage, with several traditions at the same time, enable us to understand the making and the reception of a mise en scène, which can no longer be ‘decoded’ from one single and legitimate point of view.

The fact that other cultures have gradually permeated our own leads (or should lead) us to abandon or relativize any dominant western (or Eurocentric) universalizing view.

The notion of mise en scène remains, however, central to the theory of intercultural theatre, because it is bound to the practical, pragmatic aspect of putting systems of signs together and organizing them from a semiotic point of view, i.e. of giving them productive and receptive pertinence.

Mise en scène is a kind of réglage (‘fine-tuning’) between different contexts and cultures; it is no longer only a question of intercultural exchange or of a dialectics between text and context; it is a mediation between different cultural backgrounds, traditions and methods of acting. Thus its appearance towards the end of the nineteenth century is also the consequence of the disappearance of a strong western tradition, of a certain unified acting style, which makes the presence of an ‘author’ of the performance, in the figure of the director, indispensable.

CAVITY, CRUCIBLE, CROSSING, CROSSROADS

Theatre is a crucible of civilizations. It is a place for human communication.

Victor Hugo

Is the hourglass the same top and bottom? Yes, but only in appearance. For one ought not to focus solely on the grains, tiny atoms of meaning; it is necessary to investigate their combination, their capacity for gathering in conglomerates and in strata whose thickness and composition are variable but not arbitrary. The sand in the hourglass prevents us from believing naïvely in the melting pot, in the crucible where cultures would be miraculously melted and reduced to a radically different substance, Pace Victor, there is no theatre in the crucible of a humanity where all specificity melts into a universal substance, or in the warm cavity of a familiarly cupped hand. It is at the crossing of ways, of traditions, of artistic practices that we can hope to grasp the distinct hybridization of cultures, and bring together the winding paths of anthropology, sociology and artistic practices.

Crossroads refers partly to the crossing of the ways, partly to the hybridization of races and traditions. This ambiguity is admirably suited to a description of the links between cultures: for these cultures meet either by passing close by one another or by reproducing thanks to crossbreeding. All nuances are possible, as we shall see. In taking intercultural theatre and mise en scène as its subject, this book has selected a figuration at once eternal and new: eternal, because theatrical performance has always mixed traditions and diverse styles, translated from one language or discourse into another, covered space and time in every direction; new, because western mise en scène, itself a recent notion, has made use of these meetings of performances and traditions in a conscious, deliberate and aesthetic manner only since the experiments by the multicultural groups of Barba, Brook or Mnouchkine (to cite only the most visible artists that interest us here). In this book, we will be studying only situations of exchange in one direction from a source culture, a culture foreign to us (westerners), to a target culture, western culture, in which the artists work and within which the target audience is situated.

The context of these studies can be easily circumscribed: France between 1968 and 1988, with some geographic forays. After maximal openness in 1968, there followed the ‘leaden years’ (années de plomb) of artistic and ideological isolation, elimination of dialectic thought and historicized dramaturgy, the last sparks of theoreti...