1: BUDDHISM, RELIGION AND PSYCHOTHERAPY IN THE WORLD TODAY

Shoji Muramoto

Buddhism and psychotherapy

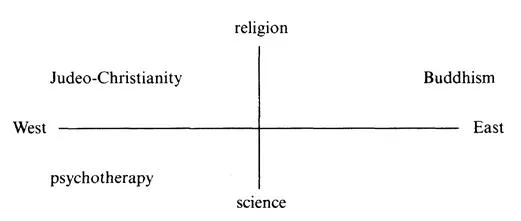

When we speak of Buddhism and psychotherapy, it is usually taken for granted that Buddhism is one of the representative religions of the East, while psychotherapy is a technique for healing mental diseases based upon modern psychology as one of the sciences developed in the West. Most discussions about Buddhism and psychotherapy therefore presuppose, implicitly or explicitly, the following diagram:

The axes of the East and the West and of religion and science intersect with each other. Judeo-Christianity and Buddhism are located respectively in the position of Western and Eastern religion, while psychotherapy is found in that of Western science. According to this diagram, both Judeo-Christianity and Buddhism are in the upper half, classified as religions, while both Judeo-Christianity and psychotherapy are in the left half belonging to the West. Because for Western people monotheism has been a historical factor without which they cannot conceive of Western culture, their discussions about Buddhism and psychotherapy refer, though not always overtly, to the connections that each has with Western religion. Westerners don’t connect Buddhism and psychotherapy simply with each other. When they speak of psychotherapy, of Buddhism, or of their mutual relationship, one can usually assume that some attitude toward Western religions is an underlying presupposition. In other words, their perspective on Buddhism and psychotherapy is more or less related to Western monotheism. On the one hand, this doubtless implies a limitation. Statements on Buddhism made by Westerners often are a mixture of knowledge gained through translations and general introductory works and their own projections on the basis of their religious experience. Buddhism then turns out to be merely the other side of Western religion as experienced by them. On the other hand, this also makes Westerners sensitive to the historical and socio-cultural limits of their statements about Buddhism. It causes a critical attitude, which is duly applied to the thinking of those living in cultures different from their own. That has nothing to do with whether they believe in their own religions or not. In my opinion, this is one of the factors historically responsible for the vigorous energy shown by Western culture.

The situation changes considerably when Japanese say something on the topic in question. Their context is different. Though it is a historical fact that Buddhism was transmitted from India by way of China and Korea, Japanese usually take it to be their traditional religion deeply connected to their native mind. Buddhism therefore, though to a lesser degree, corresponds to the function of Christianity in the West. Like the latter, Buddhism in the course of history has developed its own institutions, has itself been institutionalized. Many Japanese still experience Buddhism not so much as a way of authentic living taught by the Buddha, but as one of many institutions, part of the sociological processes of bureaucracy and functional rationality observed by Max Weber. In any case it seems remote from anything alive. This aspect does not seem to be fully appreciated by Westerners interested in Buddhism. Small wonder that they often feel disappointed when they finally come to Japan in order to experience Buddhism and find, very often, remnants of old-fashioned authoritarianism or, on the contrary, symptoms of modernization in Zen monasteries.

In Japan, psychotherapy is usually introduced without any reference to its historical and socio-cultural context as observed in the West. For the original psychotherapists, the relationship of their thinking to Western religion has always been of great concern. The question of how psychotherapy is related to traditional religion, for Japanese psychotherapists, refers to Buddhism more than to a Western creed. However, they hardly show any interest in traditional religions, be it of criticism or defense. Such an apparent indifference to Buddhism should not, however, be taken at face value. The interest in it may be latent and manifest itself only in the course of time. As a matter of fact, in recent years there has been a growing concern with traditional religion such as Buddhism and Shintoism among Japanese psychotherapists. This special issue is only one of many signs. Whereas Westerners, as pointed out above, develop a critical attitude towards their own religions, I wonder if the same thing can be said about statements on religion and psychotherapy by Japanese psychotherapists. They consider Christianity and psychotherapy to be of Western origin, and what they say about them consists of their own projections upon them on the basis of an involvement in their own culture. But when they become aware of the historical and socio-cultural limits of their thoughts, their way of thinking may gradually become more critical.

Our discussion has so far been concerned with the horizontal axis of the East and the West crossing the vertical axis of religion and science in the diagram. We have taken its validity for granted. To be sure, the two lines and the four positions help us clarify some aspects of ‘Buddhism and psychotherapy’. But does the diagram really express our concern to see the relationships among psychotherapy, and religions in the East and the West? Does it in fact help us unfold a train of thought? What is meant by each of the two axes and by their intersection? Using the diagram as a convenient scheme for explaining something is one thing. Trying to understand the meaning of the diagram is quite another. The latter is never self-evident. It turns out to be open to interpretations. The poles of each axis, the East and the West on the one hand, and religion and science on the other, can be thought of as opposite to and identical with each other. So are the two axes themselves. Let us reflect a bit upon the diagram. First we must say that it is in no way self-evident that Buddhism is an Eastern religion and psychotherapy a Western science. Such a statement has only been presupposed. The more deeply and widely one thinks, the more problematic is the character both of Buddhism and of psychotherapy.

Japanization of modern Western psychotherapy

Is psychotherapy really of the West? Indeed, almost all founders of modern psychotherapy such as Freud, Adler, Jung, Reich, and Rogers were born and brought up in the West. It is deeply rooted in Western culture. Something corresponding to psychotherapy can, however, be found everywhere in the world, so also in the East. To alleviate the suffering of the human soul and to search for its salvation lies in the nature of humanity. Could not Buddhism be called an Eastern form of psychotherapy? In Buddhist sutras and Zen texts, there are many passages with deep implications for Western psychotherapists. The dialogues recorded in them have evidently a psychotherapeutic significance. They could be examples of an Eastern version of psychotherapy. It is certainly interesting to compare them with conversations known from psychotherapeutic sessions today with regard to both form and contents. This leads beyond the concern of the present study. What I would like to propose here is that psychotherapy, as generally considered, is not necessarily of the West. In other words, I contend that Buddhism also has by nature psychotherapeutic elements.

Furthermore, modern Western psychotherapy, whether Freudian, Jungian, or other, is becoming more and more popular in Japan. Though there are still only a very few Japanese psychotherapists in private practice, the knowledge of clinical or depth psychology is widespread through the mass media. The number of those interested in psychotherapy and having experiences as therapists or as patients is definitely on the increase. We witness the emergence of a certain image of the human person intrinsically connected with the popularization of psychotherapy which American scholars have described as the ‘other-directed person’ (Riesman 1950), ‘psychological man’ (Rieff 1959), or ‘protean man’ (Lifton 1968). This phenomenon reflects to some extent the modernization of Japanese society in the sense of its Westernization. And as Berger has clearly shown (Berger, Berger and Kellner 1973), the modernization of a society is transferred to the consciousness of those who live in it. The consciousness of the Japanese is also in a process of modernization.

Yet, this aspect should be neither underestimated nor overestimated. On the one hand, there are only a few Japanese today, whether intellectuals or not, who follow the traditional way of life and are well versed in their own traditional culture. On the other hand, it cannot be simply said that the consciousness of the Japanese including psychotherapists has undergone modernization. Though various perspectives and forms of Western psychotherapy have been and are still being introduced to the Japanese one after another, it appears that there simultaneously is what may be called the Japanization of modern Western psychotherapy. This seems to me to be the fate of any foreign thought imported to Japan. In a sense, it is inevitable and even necessary that it unfold itself in a way adequate to the historically determined climate of Japan. The problem is that this Japanization is either simply ignored or justified without any serious confrontation with the original Western context from which modern psychotherapy emerged and developed. The Japanization of modern Western psychotherapy, irrespective of any differences of schools, shows, for example, in the lack of open discussions between a therapist and his client as well as between colleagues, be it in academic congresses or in therapeutic sessions, and in the relatively low appraisal of individualism leading to self-realization not only among clients but also among therapists. Bowing to social ‘harmony,’ the nature of which is seldom examined, Japanese often, consciously or unconsciously, give up what Freud recommends us to observe and respect as the basic rule of psychoanalysis: to put into words without any recourse to moral or social calculation whatever occurs to the mind. I often wonder whether psychoanalysis and Christianity were really brought to Japan despite their popularity.

Buddhism

Is Buddhism really of the West? Historically speaking, for us Japanese it is a religion that in the seventh century came not from the East but from the West. Buddhism originated in India, and was therefore transmitted from the West to Japan. Pali and Sanskrit, the original languages of Buddhist sutras and commentaries, are cognate with most Western languages. Nowadays there is a development of Buddhism in the West due in large measure to the efforts of Japanese Zen Buddhists such as Daisetsu T.Suzuki, Shin’ichi Hisamatsu and others. It is true enough that the understanding of most Westerners remains on a rather primitive level and is full of prejudices and misconceptions. At the same time, the phase of intensive introduction of Zen Buddhism to the West is gradually coming to an end. The so-called ‘Zen boom’ is certainly passing away. There is less and less ‘Beat Zen’ as one of the phenomena of the counter-culture, and instead there are more and more Western scholars who are no longer satisfied with translations or with introductions written in English, but find it very important to read Buddhist texts in their original languages. In addition, they strive to experience Buddhism directly in the Eastern countries where it has long been a central element of cultural tradition. They must be clearly distinguished from those Westerners who, unable or unwilling to confront themselves with their own Western tradition, frivolously escape to any different world. More than half a century ago, Jung already criticized such behavior severely. He said, ‘The usual mistake of Western man when faced with this problem of grasping the ideas of the East is like that of the student in Faust. Misled by the devil, he contemptuously turns his back on science and, carried away by Eastern occultism, takes over yoga practices word for word and becomes a pitiable imitator… Thus he abandons the one sure foundation of the Western mind and loses himself in a mist of words and ideas that could never have originated in European brains and can never be profitably grafted upon them’ (Jung 1929: par. 3). The new type of Western intellectuals interested in Buddhism seems wholly different from the type just described. Neither unable nor unwilling to accept Western tradition, their concern with Buddhism is not motivated by the denial of their own identity, but rather by the need for reinterpretation of themselves and their own culture. They are full of the critical spirit which has been cherished academically and religiously in the West, and can be directed both to the East and to the West.

Such a new development among Western intellectuals distinguishable from the earlier enthusiasm for Zen as a socio-pathological phenomenon can be observed, for example, in the contributions by the participants in the Kyoto Zen Symposium. They presuppose a certain breadth and depth that Buddhism has attained in America. Gomez, for example, suggests the model of a dialogue with tradition as an alternative according to which one does not have to seek or find a singular voice in it. For him the ‘nature’ of a religious system and practice is not necessarily an unchanging essence; rather, the historical reality of religion, like other human phenomena, suggests a much more complex model. He tries to combine two perspectives: that of a historian and that of a believer, and proposes to change first of all the assumption that emptiness (Sanskrit: sunyata) as a fundamental truth of Buddhism has to do with passivity and resignation. He proposes something like active emptiness. Firmly trained in the humanities, he alludes to the tasks which American Buddhists and scholars of Buddhism today find themselves confronted with, but at the same time gives relevance to Japanese Buddhists and scholars of Buddhism inasmuch as they, too, live in the contemporary world and have to play an important role therein (Gomez 1983). Maraldo poses the fundamental question ‘What do we study when we study Zen?’ After summarizing various ways of studying Zen, namely as a topic and a type, as a phenomenon and historical entity, he attempts to answer the question raised by himself, saying ‘the Zen tradition proves…a turning point which challenges those fields to clarify their methods and presuppositions’ (Maraldo 1983).

In the preface to his recent book, the former Zen monk Stephen Batchelor mentions a crisis in the present condition of Buddhist studies. Between Eastern teachers insisting upon absolute authority and Western academics studying Buddhism with scientific ‘objectivity’ he sees ‘an abyss which, despite the occasional attempts to bridge it, appears as a disconcerting vacuum’ (Batchelor 1983:22).

The general crisis of contemporary Western culture is reflected here; thus he feels ‘it necessary that Buddhist teachings speak to his contemporaries in a language that they can authentically hear.’ He continues, ‘The presentation of Buddhism in a culturally alien way of thinking often fails to totally communicate the teachings, thereby leaving us existentially untouched’ (ibid.). His involvement with Buddhism is apparently inseparable from his keen awareness of the spiritual crisis of our days. Reading the works of existential theologians and philosophers such as Paul Tillich, Gabriel Marcel, John Macquarrie, and Martin Heidegger, he finds that they as Christians were trying to deal with precisely the same problem that he was facing as a Buddhist. And he states, ‘Their writings not only gave me many ideas for a means to help resolve these conflicts, but also opened my eyes for the first time to the richness of the Judeo-Christian tradition.’

What is the East?

From the discussion so far we can see that it is never self-evident that Buddhism and psychotherapy belong to the East and the West respectively. Our situation talking about them is more complicated than we imagine. It has become quite possible to speak of Western Buddhism or Eastern psychotherapy. We must however go on to question even the terms, ‘East’ and ‘West’.

We know well that the words ‘left’ and ‘right’ are in essence relative. An object to my left will be on my right, when I turn around. It is called left or right according to the direction of my attention. This is true of all the words denoting directions in space such as ‘before’ and ‘behind’, ‘above’ and ‘beneath’. All of them are used only relatively.

On the contrary, the words ‘east’, ‘west’, ‘north’, and ‘south’ are not relative but absolute. Tokyo is to the east of Kyoto where I work, but does not become to the west of Kyoto even when I turn my back to Tokyo. It remains to the east of Kyoto so long as I work in Kyoto, whatever I may do here. Even when I go to Nagoya, Tokyo for me is in the east. But when I go to Chiba, Tokyo for me is in the west. ‘For me’ is not an exact expression because ‘east’ and ‘west’ don’t depend upon my action but upon the place where I am. The latter itself is independent of me. I only happen to be in the place. In geography we use neither ‘left’ nor ...