![]()

1

Reconstructing Crusader

Operation Crusader as a problem in historiography

One of the perennial problems of history writing is drawing lines between periods and types of evidence. What are primary documents that bear directly on events and what is secondary evidence, individual representations or interpretations of the original events? How can very different types of evidence, from laconic operational documents, private correspondence, to prolix memoirs, be measured and meshed? What are the boundaries of the contemporary and what is the meaning of proximity to an event when assessing source texts? What is being said and left unsaid, using what voices or rhetoric? In military history, as Michael Howard has pointed out,1 eyewitnesses and written records demand particular scepticism, but they may at least have the advantage of chronological priority. Memoirs by participants or observers may offer welcome details or colour but are by definition self-interested, if not self-serving.

The unusual category of ‘Official History’, however, written or supervised by military or political institutions, is pulled three ways, variously described as historiography, memorialization and didacticism,2 the need to ‘inform, persuade and defend’,3 or, more cynically, between ‘history, amnesia and selective memory’.4 All tend to blur contemporary observations with later judgements. The goal of writing history is also never strictly understanding the past, but shaping the present and/or the future. Official Histories may thus be intended for a broader audience of educated readers or a narrower one of historians and other specialists, themselves frequently involved in the production of history or policy. Indeed, the planners of the British Official History series discussed the project in just these terms.5

When addressing Operation Crusader we must distinguish between the documents of 23–26 November 1941, when the primary concern of participants was command of the battle itself, generated as part of the unfolding offensive. Next are documents originating in the immediate aftermath of Alan Cunningham’s supersession, roughly December 1941 through 1945, where individual agendas and perceptions were advanced with only a limited view towards personal legacy or the ‘judgment of history’.

This discussion therefore proceeds from a large-scale discussion of Crusader in its military and political settings, to finely detailed analyses of operational documents and correspondence with a bearing on the specific issues surrounding Cunningham’s supersession and, finally, a more broadly framed look at the writing of Crusader history.

History writing about Operation Crusader actually began shortly after the event, with the publication of early official accounts of the 8th Army and those of war correspondents, including Eve Curie, Alan Moorehead, Alaric Jacob and Alexander Clifford. The later period saw two other major historiographic streams, military memoirs by participants at various removes from Crusader and the construction of Official Histories, most importantly in Britain, South Africa and New Zealand, the principal Commonwealth nations involved in the battle.

All streams were interconnected: the official processes necessarily involved inquiries with participants and the reverse. But relationships between various Official Historians were important for acquiring information and interrogating individual narratives, a process in which preeminent military historian Basil H. Liddell Hart played multiple roles behind the scenes. In Britain writing history also entailed navigating powerful forces, including the interests of the government, represented by the Cabinet Office, and two towering, almost cult-like figures, each with a passion for constructing their own self-images, the former 8th Army commander and later Chief of the Imperial General Staff, Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, and the once and future Prime Minister, Sir Winston Churchill.6

November 1941: The military and political situations

The correlation of forces and personalities

The British Army in Egypt had been engaged in operations against the Italians since August 1940.7 The initial Italian advance was checked and then decisively repulsed, and by February 1941 British forces had advanced as west as Benghazi. But the introduction of a German expeditionary force under Erwin Rommel, and the redeployment of Commonwealth forces in March to an ill-fated defence of Greece, changed the situation completely.8

Spring was a season of disasters. By March 1941 the British had been forced back to within 100 miles of the Egyptian border. A Commonwealth garrison in the Libyan port of Tobruk was besieged, and two subsequent British offensives failed to regain the territory. In April a German invasion of Greece forced the British expedition to evacuate with the loss of all their equipment. This was quickly followed in May by the German occupation of Crete. British forces also had to be diverted from Egypt in May to contain a pro-German coup that had overthrown the Iraqi monarchy and besieged British installations there, a move that led to the British capture of all of Iraq and Syria in June and July. In August and September, Iran was occupied by British and Soviet forces.

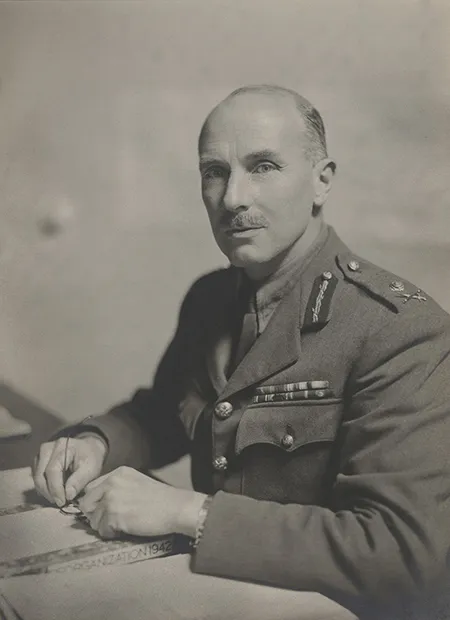

Since the outset of the war General Archibald Wavell, Commander-in-Chief of Middle East Command, had been engaged on multiple fronts, including North Africa, East Africa, Greece, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon and Iran. But after the reverses of early 1941 Wavell was relieved in June and replaced by General Claude Auchinleck,9 one of three command figures central to Crusader (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Portrait of Claude Auchinleck. Portrait by Bassano Ltd, 21 November 1940. Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery. NPG x85320.

By 1941 Auchinleck had already had a long and distinguished career in the Indian Army. He had helped develop imperial defence strategy and thus became known to many British officers, relationships that had deepened during his commands in Britain and Norway in the first years of the Second World War. His initiative in dispatching Indian troops to Iraq had permitted Wavell to reluctantly organize the relief of British garrisons there and the eventual capture of Syria. But like virtually all the military officers of the era, Auchinleck had no experience in armoured warfare.

Auchinleck’s strategic situation was as complex as Wavell’s, only with growing concerns regarding the success of Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union in June, and the possibility of war in the Far East with Japan. Political pressure for a successful British offensive in North Africa from Prime Minister Winston Churchill was also growing. With a steady increase in manpower and supplies, especially tanks, flowing to British forces, Operation Crusader was conceived as means to destroy Rommel’s recently introduced Afrika Korps and lift the siege of Tobruk.

Appointed command of the newly formed 8th Army in August 1941 was Lt General Alan Cunningham (Figure 2),10 who had previously commanded East Africa Force. Cunningham’s rapid defeat of much larger Italian forces in Somaliland and Ethiopia during April and May had been a rare victory in an otherwise bleak string of British defeats. It was hoped that the tactical cleverness and daring that Cunningham had displayed in the mountainous highlands of East Africa would be repeated in the desert. But he had even less experience, and possibly appreciation, of armoured warfare than Auchinleck, and certainly less than his new subordinates.

Figure 2 Portrait of Alan Cunningham, 21 November 1941. Imperial War Museum, E 006661. Courtesy of the Imperial War Museum.

Cunningham was a Royal Artillery officer who had briefly commanded several divisions in Britain prior to being assigned to East Africa Command. While he was mostly unknown to the British officers who had fought in the desert, his brother, Commander-in-Chief, Mediterranean Fleet Admiral Andrew B. Cunningham, was one of Britain’s most famous military figures. Cunningham’s Mediterranean fleet was critical for keeping supplies flowing to Egypt, ensuring the survival of the colony at Malta, and for control of the Suez Canal and the route to India. By the fall of 1941 Cunningham had already led the fleet to important victories over the Italians at Taranto and Cape Matapan, and had facilitated the rescue of tens of thousands of British soldiers from Greece and Crete.

The third figure in question was Alexander ‘Sandy’ Galloway, assigned as Brigadier General Staff (BGS) of 8th Army (Figure 3). Earlier in 1941 Galloway had commanded the 23rd Brigade, which had a relief role in the brief campaign against Syria. Galloway had previously served as Lt General Henry Maitland ‘Jumbo’ Wilson’s BGS in the expeditionary force in Greece and played a key role in organizing its subsequent evacuation. Prior to that he had been BGS when Wilson commanded British troops in Egypt and had helped plan Lt General Richard O’Connor’s December 1940 victory against Italian forces, Operation Compass.

Figure 3 Portrait of Alexander Galloway. Portrait by Walter Stoneman, September 1942. Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery. NPG x164368.

Unlike Cunningham (Figure 4), Galloway’s experience with desert warfare stretched back to the Sinai and Gaza campaigns in the First World War, and from 1932 to 1934 he had been Brigade Major to Frederick Alfred (Tim) Pile in the Canal Brigade in Egypt (one of whose battalions was commanded by Bernard Montgomery). Both figures would later have hidden roles in shaping the story of Crusader.

Figure 4 Alan and Andrew Cunningham, October 1941. Imperial War Museum, E 3550e. Courtesy of the Imperial War Museum.

With the increased flow of supplies to British forces in Egypt, and pressure from Churchill growing for an offensive, a plan was developed. The Western Desert Force was reorganized into 8th Army, consisting of 13 Corps, under Lt General Alfred Reade Godwin-Austen, and 30 Corps, under Lt General Willoughby Norrie. Both formations included British and Commonwealth forces but 30 Corps was allocated most of the heavy ‘cruiser’ tanks while 13 Corps comprised infantry and light tanks. The final plan for Operation Crusader envisioned the 30 Corps crossing the Libyan border and then swinging north to engage and defeat German armour at Gabr Saleh, a point in the desert between the two primary east–west roads. The 13 Corps would pin down Italian forces closer to the coast and then push through towards Tobruk once the German armour threat was eliminated.

The separation of armour and infantry conformed to British doctrine that was predicated on the fanciful notion of a decisive desert tank battle on the analogy of a naval engagement at sea. The Crusader plan also called for British armour to cross mostly flat and featureless terrain towards an arbitrary point with the hope of encountering and then destroying Rommel’s armour forces, which operated on a combined arms concept, calling for close cooperation between infantry, armour, artillery and air support.11

Compounding British difficulties were an inadequate and fragile communications network,12 weaker anti-tank weapons and tactical underestimation of German anti-tank capabilities,13 a propensity to retreat into ‘leaguers’ (from the Afrikaans laager) at the end of the day rather than to secure the battlefield, and general overconfidence. A longstanding official mindset that celebrated amateurism, martial spirit, regimental tradition and lack of coordination over professionalism and cooperation was about to be tested, along with the sweeping and disconnected metaphors of Britain’s armoured warfare advocates.14

The British intelligence and air power situations were more positive. Substantial amounts of Italian and German communications traffic were being decoded, and as of the fall of 1941 the Commander-in-Chief of the 8th Army was included as an Ultra recipient.15 These sources gave access to frank German assessments regarding their own supplies and a fairly accurate picture of German capabilities and intentions. This included plans for a German attack on Tobruk that affected the timing of the British offensive. Complex deception operations were thus developed to confuse the Germans regarding the timing and axis of the British offensive. Intelligence sources also gave Auchinleck a detailed view of the German order of battle and logistics that would be critical to his decision to continue the battle and to relieve Cunningham.16

Air power was another area where the British had a narrow advantage, in terms of numbers of aircraft, support and infrastructure, command and control, and a nascent approach to close air support.17 Finally, British medical services were far more advanced than the Germans, as were the general hygiene levels of British forces.18 Using Cairo, Alexandria, the Canal Zone and the Nile Delta as a base, connected to British territories in Palestine and ultimately to India, was another immeasurable help. In preparation for Crusader rail lines were extended west and large supply dumps were established to support the offensive.

But the British military situation was again offset by Axis advantages, including better tactics and anti-tank weapons, their own field and signals intelligence,19 and intercepted intelligence reports from the American military attaché in Cairo.20 While the British had overall superiority in numerical terms (e.g. 724 tanks versus Rommel’s 414),21 serious misunderstanding of German anti-tank capabilities led to overconfidence ...