![]()

1

Different conceptions of decision-making

Should a seller in a prominent position in its market, knowing potential customers will sample its goods before those of its rivals, charge a higher or lower price than its non-prominent competitors? Should a government increase competition or information provision in order to protect customers from being exploited by charlatans selling services of no actual value? Should we allocate our limited memory across all the decisions we have to make or should we devote it to only one of them? A research project in the 1950s at the Graduate School of Industrial Administration at the Carnegie Institute of Technology (now part of Carnegie Mellon University) led to two very different views of how we make decisions, which have very different implications for questions such as these. This project split the Graduate School, and the economics discipline as a whole, in two, but also led to the concept of bounded rationality, the study of which has become one of the most interesting and wide-reaching fields of economics. We explore this field in what follows, which will take us into the realms of mathematical modelling, artificial intelligence and cognitive science. It will also lead to surprising insights about situations as diverse as how businesses should launch new goods, the likelihood of centrist candidates being successful in elections and how governments should protect our interests most effectively. This exploration will enrich our understanding of the everyday situations in which we find ourselves and will at times show what we think has been proved by traditional economics to be incorrect, even harmful.

The schism

The research project focused on how businesses make decisions and was conducted by a team made up of some of the smartest minds in the field. John Muth’s interpretation of the resulting data was that businesses make their decisions according to what became known as rational expectations. According to this view, businesses are able to accurately identify relationships and lines of causation between the variables that are relevant to them. They are able to quickly establish the likely effects of any changes in their environment, enabling them to continuously identify their optimal courses of action. They may be caught off guard by an unexpected change, but such an oversight will be short lived as the new information is quickly accommodated. A saying that has been attributed to Abraham Lincoln summarizes this view nicely: “You can fool some of the people all of the time, and all of the people some of the time, but you cannot fool all of the people all of the time”.1 Muth’s view was that businesses are essentially able to process information as effectively and thoroughly as econometricians who possess the most up-to-date computational power. Herbert Simon’s interpretation, on the other hand, was starkly different. Simon asserted that businesses are usually unable to perfectly process the vast amount of relevant information and so seek outcomes that are simply good enough rather than optimal. This is bounded rationality.

Work on both concepts subsequently led to awards of the Nobel Prize in Economics. Herbert Simon received the award in 1978 for “pioneering research into the decision-making processes within economic organizations”; whereas Robert Lucas Jr, also from Carnegie-Mellon, received the award in 1995 “for having developed and applied the hypothesis of rational expectations”: an indication of the importance of both.2 At the time, however, economists at the Graduate School and beyond adopted Muth’s interpretation and rejected that of Simon. And this rejection was so fierce within his department that Simon relocated his office to the Psychology Department: the field in which both he and his work have been most readily accepted ever since.3 Even upon receiving his Nobel Prize, Simon lamented that “my economist friends have long since given up on me, consigning me to psychology or some other distant wasteland”.4

Rationality: complete and bounded

Complete rationality refers to our ability to make decisions we consider to be optimal, based on information regarding the past, present and future. The assumption that we all act as if in a completely rational manner has dominated the work of economists since the 1950s. It is a logical assumption to make, with any anomalies surely being cancelled-out at the aggregate level. It is also applicable to any situation we face and is relatively easy to model mathematically, involving optimization techniques that students are taught in the first year of their degree courses. This last advantage cannot be underestimated in a discipline that values technical rigour so highly. The assumption of complete rationality is so well ingrained in the subject that it underpins the increasingly sophisticated models used by economists without usually being questioned or even considered: it is just the way economics is done. However, upon closer inspection its rather unrealistic nature becomes abundantly apparent.

Consider an individual who walks into a store to purchase wine and cheese for an evening with friends. She has £M to spend, the wine costs £PW, and the cheese £PC. How much of each should she buy? To answer this question, we need to work through the following steps:

1.We make an assumption about what she wants to achieve and, usually, we assume she wants to maximize her utility: the overall satisfaction she enjoys from the wine and cheese she buys.

2.We assume she knows how much utility she will gain from each possible combination of wine and cheese and is able to rank those combinations in a consistent order of preference.

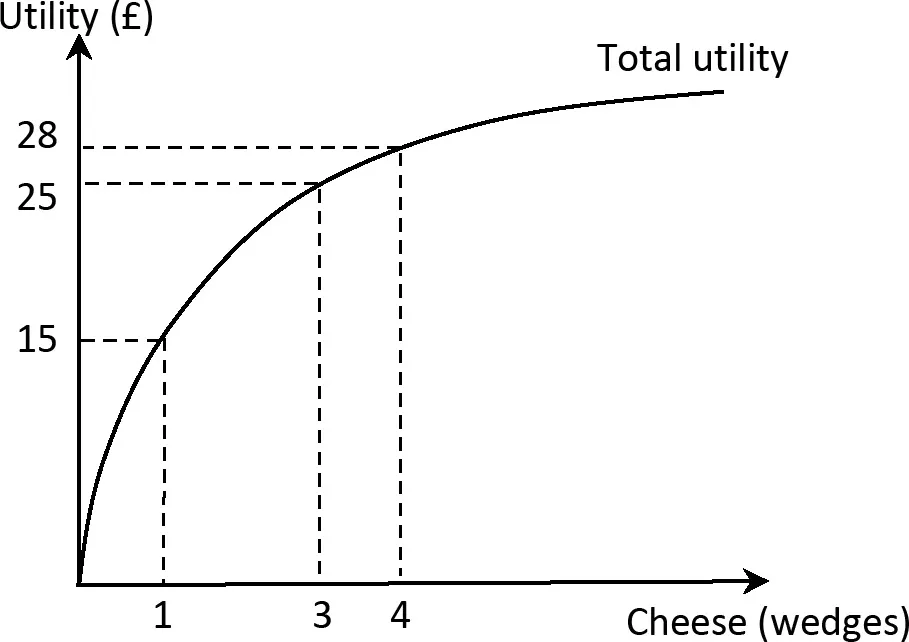

3.We consider the law of diminishing marginal utility, which simply says the additional satisfaction she experiences from purchasing one extra wedge of cheese declines the more of it she buys. This law is illustrated in Figure 1.1, which traces the total utility she enjoys from consuming different amounts of cheese. The first wedge brings her utility valued at £15 whereas by the time she has already bought three, an additional wedge brings only £3 of additional utility. (In the cases of both cheese and wine it isn’t inconceivable that after a certain amount of consumption total utility actually declines). The logical extension of this is that she is likely to prefer moderate amounts of wine and cheese rather than a lot of one and very little of the other.

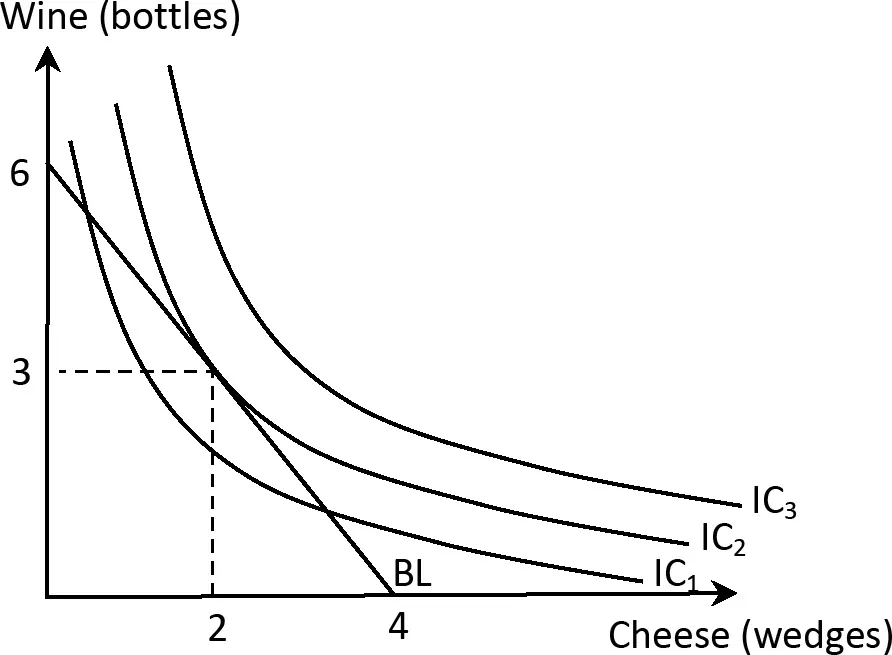

4.We draw her indifference curves, shown in Figure 1.2, which trace the combinations of the two goods that offer her exactly equal amounts of total utility and so between which she is completely indifferent. Assuming she doesn’t reach the levels of consumption at which further amounts of either good actually detract from her overall utility, we can assume her preference increases with more of both goods and so she prefers all the combinations represented by IC3 to all those represented by IC2.

5.We add her budget line (BL) to this diagram, which represents the combinations she can exactly afford by spending every penny she has. In this case, for example, she can afford six bottles of wine and zero wedges of cheese or four wedges of cheese and zero bottles of wine.

6.With her preference increasing with the amount of both goods she buys, she wants to purchase the combination that is on the highest indifference curve she can afford and so we can identify her optimal choice as being three bottles of wine and two wedges of cheese.

This is the model of complete rationality.

At first glance this analysis appears straightforward enough and sufficiently simple and reasonable for economists to use as the basis of their models. However, it implies that when we walk into a store we’re able to identify the combination of goods for which the ratio of the extra utility one additional unit of each brings us (the ratio of the goods’ marginal utilities and the slope of our indifference curves) is equal to the ratio of the goods’ prices (the slope of our budget lines). And that is in the simplest of cases where there are only two goods. For more realistic scenarios, in which we have to decide how much to purchase of each of a much larger number of goods, it implies we can somehow identify the quantities at which the ratio of marginal utility and price is exactly the same for each and every good: the equi-marginal principle. Even though economists are careful to explain this is a prescriptive rather than descriptive assumption, that it is intended to represent rather than describe our behaviour, it does not take the inclusion of too many additional goods to make it seem unrealistically demanding. Do we really behave as if in this manner, even for such relatively simple purchasing decisions let alone the more complex decisions surrounding marriage, divorce and addiction, all of which have been analysed in this way?

Figure 1.1 Law of diminishing marginal utility

Figure 1.2 Indifference curve analysis

Herbert Simon didn’t think so, remarking that “as soon as we turn from very broad macroeconomic problems and wish to examine in some detail the behavior of the individual actors, difficulties begin to arise on all sides”. For Simon, in all but the very simplest of situations we are simply unable to identify, assimilate and process information in an optimizing manner: “the capacity of the human mind for formulating and solving complex problems is very small compared with the size of the problems whose solution is required for objectively [completely] rational behavior in the real world – or even for a reasonable approximation to such objective rationality”.5 Simon likened this situation to a pair of scissors, with one blade representing the often voluminous and complex information bearing down on us as we seek to make a decision and the other representing our limited (bounded) cognitive capacity. In such situations, possessing cognitive capacities insufficient to deal with the complexity of the decisions with which we grapple, we cannot identify and choose the optimal options and so, by necessity, employ alternative strategies to make our decisions. This is the principle of bounded rationality.

It is important to note the relational nature of this concept. Simon certainly wasn’t proposing we are unintelligent, just that the complexity of the decisions we often face precludes us from making them optimally. In cases involving simpler decisions, we certainly will seek to optimize our outcomes.

Causes of bounded rationality

There are three different explanations for why we are characterized by bounded rationality, relating to the way the types of decisions we make have evolved over time, to the ever-expanding volume of decisions we make and to the way our brains naturally process information.

The first of these ...