![]()

Part I

Leadership in Higher Education

![]()

1

Introduction

Leadership and learning are indispensable to each other.

John F.Kennedy

Leadership and Change in Higher Education

I have prepared this book against a background of momentous change in higher education. Everyone who works in a university knows just how troublesome these days are. There is no prospect of them becoming any easier in our lifetimes. It is idle to pretend that the growing pressures placed on universities in the last few decades by governments, employers and students will abate. We face an almost certain future of relentless variation in a more austere environment. There will be more competition for resources, stronger opposition from new providers of higher education, even more drastically reduced public funding. There will be even greater pressure to perform and be accountable combined with the challenges of new forms of learning, new technologies for teaching, and new requirements for graduate competence. Underlying all this is deep uncertainty about the proper role and functions of different universities in systems of mass higher education. And to complete the picture, these changes and uncertainties must be managed through the medium of an academic workforce whose confidence and spirit have been severely degraded.

This is a book that aims to help academic people address this seemingly depressing future with vigour, energy and optimism. These are sharp and stimulating times. These are the times when leadership comes into its own. It is the task of academic leaders to revitalise and energise their colleagues to meet the challenge of tough times with eagerness and with passion. We have seriously underestimated the power of leadership in higher education. It is perhaps the most practical and cost-effective strategy known to organisations that are struggling to survive and to make progress through troubled waters. As I hope to show through reporting the experiences of academic staff, it can transform the commonplace and average into the remarkable and excellent. The most substantial advantage a university in a competitive and resource-hungry higher education system can possess is effective academic leadership.

Yet these are not the only reasons why learning to lead in higher education is a course deserving our attention. The process of learning to lead is itself an intensely satisfying experience for those who undertake it; it is a process of developing expertise and growing as a person. People move from a search for ‘right answers’ to a realisation that they possess a store of tacit knowledge that they can use to make better judgements about people and resources. Moreover good leadership, as we shall see, can make academic work a more enjoyable and more productive experience for everyone— including the leader. My aim is to convince readers that it is worthwhile learning how to lead.

There are two dangerous myths of academic life related to academic leadership. One is that management is an intrusive and unnecessary activity which confines academic freedom and wastes the talents of a leader such as a head of department in trivial administrative tasks. The other is that academics are a fundamentally unproductive group who need the exercise of some managerial power and control to get them out of bed earlier in the morning. There is still far too much unprofessional academic leadership, of both these kinds—excessively lax and responsive, or dumbly aggressive and assertive—at all levels of universities. Staff are rightly critical of both types. They will never give their best to people who appear not to understand them and their needs. Too much of academic management in the past has been reactive, leisurely, cloistered, and amateur. Too much of academic leadership in the present is focused on short-term goals and betrays a lack of trust in people. There are ditches on both sides of the leadership road, and I will try to show how to plot a course to avoid them, through listening to the experiences of our colleagues, and learning from them.

Academic Leadership: Process and People

When I refer to leadership in this book, I mean nothing mysterious or obscure. Nor do I mean only the people who retain titles such as head of department or vice chancellor, although it will often be these people who carry the greatest leadership responsibilities. I imply instead a practical and everyday process of supporting, managing, developing and inspiring academic colleagues. In this second sense, leadership in universities can and should be exercised by everyone, from the vice chancellor to the casual car parking attendant. Leadership is to do with how people relate to each other.

However, while I hope that everyone who works or studies in higher education will benefit from reading it, the book is addressed primarily to a certain group of staff. These are people who are, or have recently been, researchers and teachers; those who occupy academic positions and work in universities as ‘middle managers’ of academics and support staff. Typically these people are called heads of academic departments.

In many British and Australian universities, this traditional role has gained new importance and new duties as institutions have struggled to respond to unfamiliar demands. As long ago as 1988 a standard text on academic leadership in the USA could assert that the ‘quality of the core academic success of the institution depends upon the quality of the chairpersons— their dependability, their resourcefulness, their appreciation of academic values, and their insight into the abilities and weaknesses of their colleagues’ (Bennett, 1988). Now more than ever in the UK, Australasia and much of Asia, the position is a key one. Now more than ever heads of departments stand at the three-way crossroads between the world external to the university, the people who constitute its senior management, and its academic and support staff. Heads must look to the future and survive the present. They must maintain standards of teaching and research output with fewer inputs. They must somehow motivate a group of workers whose status, prospects and job security relative to similar professionals, and their own profession a generation ago, have plummeted. They must be superb planners and competent business people who are not averse to risk-taking and enjoy entrepreneurial activity. That most of these staff require new skills, and more knowledge, development and support is not in question. Leadership is about learning.

Oscar Wilde defined ‘experience’ as the name we give to our mistakes. The memory of my experience of the first few months of being the director of an academic work unit remains vivid. I could not have been more naive, despite my twenty-odd years in higher education and fair reputation in my special field. I had no conception of the processes of budgeting, strategic planning, managing staff, or even how I should work with a secretary. I had hazy ideas about running staff meetings and allocating workloads. I had vague notions of inspiring staff and celebrating their attainment culled from airport books on leadership. No-one asked me to compile a set of goals for my performance and to discuss what indicators of achievement I would like to use. I had thought I had worked reasonably diligently as an academic, but the workload of being an academic leader and the constant oscillation between different types of problem during a normal day took my breath away.

In these experiences I was certainly not unique. I shall try to demonstrate that universities have a long road to travel before they have fully mastered the process of developing their leaders. Their achievement of this objective will determine their future prosperity in the no-holds-barred adverse market of contemporary higher education. No book can be a substitute for making mistakes and learning from them, but I hope that this one will help both new and experienced heads to master some of the principles of effective academic leadership. Since the process of reflection is the engine that drives performance improvement among professionals, I hope it will also help them reflect profitably on their experiences as part of a lifetime programme of improving their leadership ability.

A central idea of this book is that we can enhance our leadership performance through studying the experiences of academic staff. Running through it is the idea of listening to them about the challenges they encounter and the kind of academic work environment which enables them to achieve success. ‘Leadership develops’, said an experienced school principal, ‘Not through either responding or asserting. Rather it develops through establishing a foundation of productive responses to people’ (Donaldson, 1991).

With this in mind, an appropriate starting point is an examination of the views of a sample of heads of departments about the leadership issues they face in today’s higher education environment. In the next chapter I will look, among other things, at how heads foresee the future organisational structures of their universities.

Academic Leaders’ Views of Leadership Challenges

During 1996 I used electronic mail to survey a hundred university staff from the UK, Hong Kong, Singapore, New Zealand and Australia who occupied positions as heads of department. The institutions surveyed included ancient foundations and ‘new’ universities. I asked them to nominate up to three key challenges facing academic leaders such as themselves in the years 1997– 2005.

The most nominated area concerned maintaining quality with diminished resources, or ‘doing more with less’. Three quarters of the respondents mentioned this type of challenge. The issues mentioned included better financial management, survival in a leaner environment, strategies for establishing new student markets, balancing teaching and research funds, income generation, gaining more research support, and achieving high quality research with reduced funding.

The second most mentioned area was the management and leadership of academic people at a time of rapid change, named by sixty per cent of heads. This included selection and recruitment, helping staff through change, developing new skills, setting clear goals, mentoring younger staff, helping staff to cope with increased workloads, maintaining motivation and morale at a time of declining public respect for the profession, and rewarding performance.

Next in the frequency order came issues associated with turbulence and alteration in the environment of higher education, mentioned by over a third of heads. These consisted of the need for vision and innovation in teaching and research, problems of technological change, information overload, and the globalisation of higher education markets.

A similar proportion of heads mentioned student numbers and standards—attracting more students, teaching students who were less academically motivated and less well-prepared, and responding to the need to develop students’ lifelong learning skills.

The only other area mentioned by more than ten per cent of heads was the personal dilemma of balancing their own academic work (especially continuing to produce research output) with the demands of leadership and administration.

Table 1.1 summarises these responses. Less frequently nominated topics included the need to reduce bureaucracy and improve administrative processes; the need for more regional and international collaboration; the need for more cooperation between universities; and the need to maintain a strong defence against government attacks on higher education. Perhaps surprisingly, only one respondent mentioned the challenge of ‘getting rid of managerialism’ and returning to more traditional forms of collegial university administration.

Table 1.1 Main challenges 100 university leaders say they face

| Challenge | Frequency of mention |

| Maintaining quality with fewer resources; doing more with less; stretching and managing budgets | 76 |

| Managing and leading academic people at a time of rapid change | 60 |

| Turbulence and alteration in the higher education environment | 35 |

| Student numbers and responding to new types of students | 33 |

| Balancing own academic work with the demands of being an academic leader | 15 |

Challenges and Models

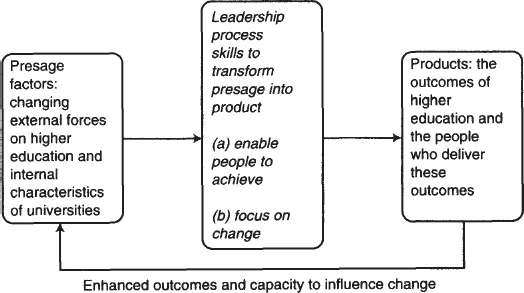

Most of the challenges recognised by academic leaders at head of department level can be understood in terms of the simple ‘systems model’ at Figure 1.1. The core academic leadership responsibility represented by the middle block is twofold. We will find ourselves returning again and again to this dual accountability as we move through the following chapters.

First and foremost, academic leadership must provide the means, assistance and resources which enable academic and support staff to perform well. Leadership is about producing excellence. Second, it must focus on change and innovation, and the harnessing of traditional academic values and strengths to meet new and sometimes strange requirements. Leadership is about change. Higher quality outcomes, and people geared to change, combine to influence the internal and external presage factors in the system by means of the feedback loop shown, and thus generate more favourable conditions for effective academic leadership processes.

In addressing this agenda, a recurrent theme of the book is the problem of managing conflicting priorities. Leadership is about tensions and balances. The concept is embodied in an old German proverb: ‘Those who would rule must hear and be deaf, see and be blind’. We must trust people; but not everyone can be trusted. We must focus on traditional academic values; but we must also respond to new demands from employers, companies, governments, and students. We must look outwards to the strategic advantage of our work unit; but we should never neglect internal processes and relationships. We must listen and consult; but we must have the wisdom to know when the advice we receive is correct. We must walk ahead; we must also serve. We must be risk-takers; we must also be reliable risk assessors. We must manage efficiently and firmly for today; we must lead people sensitively so they can independently address the new problems of tomorrow. We must mentor our staff; we must also assess their performance. We must enhance the quality of student learning; we must ensure the scholarly productivity of our colleagues. And we need to decide the degree to which our careers as academics are to be traded against our careers as academic managers.

Figure 1.1 A simple ‘model’ of academic leadership

Reconciling these differences means that academic leaders need to combine several qualities in order to survive. They must be ...