- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A mix of theory and practical applications, Placing Shadows covers the physical properties of light and the selection of proper instruments for the best possible effect. For the student, advanced amateur, and pros trying to enhance the look of their productions, this book examines the fundamentals and is also a solid reference for tips on better performance.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Placing Shadows by Chuck Gloman,Tom LeTourneau in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

Film & VideoChapter 1

The Physics of Light

Starting on the Right Wavelength

Light is a particular range of electromagnetic radiation that stimulates the optic receptors in the eye and makes it possible to determine the color and form of our surroundings.

Light has three properties that contribute to our perception of the things it illuminates:

• color

• quality

• intensity

Lighting directors must have a basic understanding of all three properties, from a scientific point of view, to make an artistic contribution to the productions they are lighting. In Chapter 1, we will deal with the aspects of color and quality; in Chapter 3, we will discuss the quality of light provided by various lamp and reflector types; and in Chapter 4, we will discuss aspects of intensity.

Color

We know that the light of the sun or of an electric lamp can be broken down into the colors of the rainbow. The common method for dispersing white light is by using a prism. As a young science student you may have learned the memory crutch Roy G. Biv to help you remember the colors and the order they fall in when white light passes through a prism and is projected on a white surface.

Primary Colors

Light has two components: luminance information and chrominance information. The luminance information deals with the amount of light intensity in lumens and is measured in foot-candles. Chrominance (color) information is subdivided into two factors: hue or tint, and saturation.

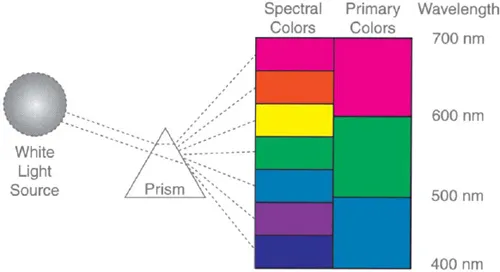

Hue defines color with respect to its placement within the spectral range, as shown in Figure 1.1. It is the basic color of the light. The term “tint” is often used interchangeably with hue in defining chrominance and in labeling the monitor control that adjusts that aspect of color.

Saturation is the property of light that determines the difference from white at a given hue. In other words, heavily saturated red might be described as fire-engine red. A poorly saturated red is closer to white in value and may be called pale pink. Unfortunately, most monitors just label the saturation control as color.

To understand saturation, think of color as a specific hue that gradually increases in intensity along a straight line from white at the left end to the pure color on the right. The pure color—for example, red—is said to be saturated, while its unsaturated hue is called pink. Adjusting the color control of a monitor or television affects the degree of color saturation in the scene.

Figure 1.1: The spectral colors.

Figure 1.1 shows that white light consists of at least seven distinct colors, known as the spectral colors. We know from observation that there are a great many other colors in the world around us. In the great scheme of things, these seven colors are of no particular importance except to illustrate the concept of refraction and that white light has distinct component parts—parts that can be measured. There are three primary colors, however, that are extremely important in understanding the physics of light and the transmission of color pictures by the television system. These colors, the capital letters of the name Roy G. Biv, are red, green, and blue. They are the primary colors of light. Various combinations of these three colors make it possible to reproduce all the other colors in the visible spectrum. Since this is true, we need only evaluate everything we see in terms of how much red, green, and blue light it reflects to reproduce its actual color. That is why the television camera has three pickup chips, each one reacting to the percentage of a particular primary color reflected by the subject. The display screen, a cathode ray tube (CRT), contains red, green, and blue phosphors that glow with an intensity relative to the signal generated by the corresponding pickup chips in the camera.

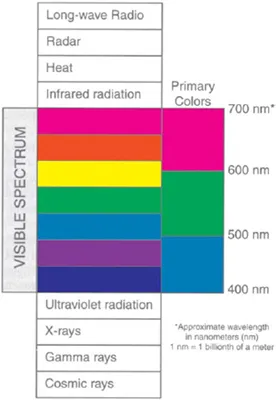

While the knowledge that white light could be broken down into seven colors in a particular order may have gotten us through our science test, we need to understand the color aspects of light in greater detail to understand how it affects the television camera (see Figure 1.2). Red has the longest wavelength of visible light. The farther you proceed toward the violet, or opposite, end of the spectrum, the shorter the wavelengths become. People commonly use the term “warm” to identify light in the red-orange portion of the spectrum and “cool” to describe light in the blue-violet end of it. These terms are subjective evaluations that relate to the perceived or psychological effect of these colors on the viewer. These terms should not be confused with the objective measurement of the actual spectral composition of a light source known as the “color temperature.

Color Temperature

The color temperature of a light source is determined by the wavelengths of light it emits. That is, how much red light, how much green light, how much blue light, etc. We know that as an object is heated it will first glow with a reddish color. If we continue to apply heat, it will give off a yellow light and change to blue and then violet as additional heat is applied. Because different substances emit different wavelengths of light when heated to identical temperatures due to their differing chemical compositions, a specific substance must be used to establish standards.

Such a standard is called a “blackbody.” This mythical body, or substance, is said to be composed of a material that neither emits nor reflects any light whatsoever. When it is heated to a specific temperature, it gives off a specific combination of wavelengths that are consistent and predictable. The temperature scale used is Kelvin (K), in which 273° Celsius is absolute zero. In theory, when we heat this body to a temperature of 3200°K, it will emit a certain combination of wavelengths through the yellow end of the spectrum. It is classified as “white light” because it contains sufficient wavelengths of all the colors of the visible spectrum which, when added together, form white. If we continue heating the body to a temperature of 5600°K, it will emit additional wavelengths nearer the violet end of the spectrum.

Figure 1.2: Electromagnetic spectrum and approximate wavelengths in nanometers.

The important part of this definition is that the light emitted during the heating process progresses at a gradually increasing rate from the longer red wavelengths to the shorter wavelengths in the blue-violet end of the spectrum. This phenomenon occurs only when a tungsten filament is heated by passing a current through it. Incandescent lamps produce this gradual, predictable increase when current is applied to their filament.

For reasons both scientific and economic, tungsten is the metal of choice for manufacturers of lamp filaments. Since the melting point of tungsten is 3800°K, a working temperature of 3200°K has been chosen as the standard for tungsten lighting. At an operating temperature of 3200°K, a tungsten filament will have a relatively long life span and still produce a desirable spectrum. The tungsten lamps designed to burn at 3400°K for special photographic applications have greatly reduced life spans due to higher operating temperatures. The closer you operate a filament to its boiling point, the shorter its life.

Some tungsten-halogen lamps are rated at 5600°K, or “daylight.” Since the filament will vaporize at 3800°K, how can a color temperature of 5600°K be achieved? The answer is the application of dichroic filters. These are special optical coatings applied to the front of daylight lamps that reduce the colors complementary to blue and produce a pseudo-daylight spectrum. Most daylight sources, like the halogen metal iodine (HMI) lamps, are the result of specially designed discharge lamps that generate the higher color temperature without the need for special dichroic coatings that reduce output and lamp efficiency. No true blackbody source can produce the daylight spectrum, since no metal filament can be heated to 5600°K or higher, without melting.

Fluorescent lamps, on the other hand, do not produce light as the result of passing current through a filament. Instead, an arc of current passes through a combination of gases, excites them and causes a phosphor coating inside the lamp to glow. Such light sources do not produce a continuous spectrum and are very difficult to correct and balance with standard light sources. Sometimes you may see a correlated color temperature listed for some fluorescent lamps. Generally, such a listing will rate a cool white lamp at 4200°K and a warm white fluorescent lamp at 2900°K. Do not be misled by such ratings, however. They are not really scientific and do not provide satisfactory results when you add filters based on those temperatures to such a source. It merely means that a certain number of people have looked at this light source and agreed that it appears to the human eye to produce a blackbody color temperature that correlates with 2900°K or 4200°K. It is not actually 2900°K or 4200°K. No light sources, other than incandescent lamps, are true blackbody sources, measurable in degrees Kelvin.

Fluorescent lights, mercury vapor lamps, sodium vapor lamps, and various other multivapor discharge sources all produce a very erratic spectrum and cannot be rated in degrees Kelvin as blackbody sources can. The actual wavelengths produced depend on the composition of gases and the coatings on the interior of the lamps. The spectrum they produce does not provide a true white light containing known wavelengths from the red end of the spectrum to the violet end. Since they do not produce a true white light, they are very difficult to color-correct with filtration media (see the section later on in this chapter, “Working with Sources of Mixed Color Temperature”).

Color Rendering Index

A more scientific approach to the classification of the apparent color temperature of fluorescent and other discharge lamps is recommended by the International Commission of Illumination. That method is the color rendering index (CRI), in which eight standard pastel colors are viewed under the light source being rated and under a blackbody source of known color temperature. The color rendering index ranges from below zero to 100. A number on that scale is assigned to the rated source light based on how accurately it renders the pastel colors compared to the same swatches viewed under the blackbody source. The closer they come to matching the look of samples under the blackbody source, the higher the index number assigned to the source being tested. Cool white fluorescent lamps are given a CRI of 68. Warm white fluorescent lamps have a CRI of 56. Daylight (Daylite) fluorescent lamps have a CRI of 75. A special fluorescent lamp called the Vita-lite has a CRI of 91 and comes as close as possible to a natural or daylight source.

Light radiates from the source in waves. The length of these waves, when measured from peak to peak, varies with the color involved. As mentioned earlier, the longer wavelengths are near the red end of the spectrum. These are perceived as being warm in color. The shorter wavelengths, near the violet end of the spectrum, are perceived as being cool in color.

While the human eye is capable of adapting to a wide range of color temperatures and interpreting color correctly, the pickup chips of the television camera cannot. Television cameras are designed to produce accurate color when the scene is illuminated with light at 3200°K. Within a given range the camera circuits can compensate for slight deviation from the ideal 3200°K color temperature (see the next section, “Auto White Balance”). This color temperature is often referred to as “tungsten” light. The other general color temperature classification is “daylight.” It ranges anywhere from 5400°K to 6800°K. These color temperatures are usually found when shooting in sunlight or under specially balanced or color-corrected studio lights.

Camera Operation

Before plunging into a technical explanation of camera operation or, later on, proper setup techniques for a color monitor, let me say a word about why such topics are covered in a text about lighting.

To make valid judgments about your lighting efforts, you must be able to view the results through the system. A number of texts dealing with TV lighting state that your monitor should be properly adjusted before you can make a valid assessment of the scene. They do not, however, tell you how to adjust it properly. Understanding proper adjustment methods is important for both the independent video producer who must know some basic aspects of lighting and for lighting designers who work with monitors daily.

In Figure 1.3, we see that the light that passes through the lens is split up by the prism block by a charged coupled device (CCD) into three primary colors. Each CCD chip then produces a voltage signal that is relative to the amount of that particular color present in the image at any given location. For example, if we were shooting a primary red art card, the red chip would produce the entire signal, and the green and blue chips would produce no signal at all.

According to the National Television Systems Committee (NTSC) standards for American television, the camera should be set up to produce a 1-volt signal, from peak to peak, when it is properly adjusted. In the case of shooting the red art card mentioned earlier, that entire signal would be produced by the red chip. However, we rarely shoot a subject that contains a single primary color, so all pictures will be composed of varying voltages from each of the three CCD chips. Since white contains all the colors of the visible spectrum, we can reason that if we reproduce white accurately, we will automatically reproduce individual colors accurately. When white is reproduced on television there is a definite ratio among the three primary colors. In that ratio, r...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Dedication

- Introduction

- Acknowledgments

- Preface

- Chapter 1: The Physics of Light: Starting on the Right Wavelength

- Chapter 2: Meters, Monitors, and Scopes: Looks Good Here!

- Chapter 3: Lamps, Reflectors, and Lighting Instruments: What Is the Difference?

- Chapter 4: Video Contrast Ratios: Help, They Don’t Match!

- Chapter 5: Instrument Functions: What Do They Do?

- Chapter 6: Terms and Tips: Control Yourself

- Chapter 7: Basic Lighting Setups: Where Do They Go?

- Chapter 8: Avoiding Problems: Be Prepared

- Chapter 9: Location Lighting: Battling the Elements

- Chapter 10: Studio Lighting: The Good Life

- Chapter 11: Future Directions: Watts New?

- Chapter 12: Specific Lighting Situations: What Should I Do?

- Chapter 13: Glossary, Terms and Tips: Control Yourself

- Appendix: Resources for the Lighting Professional

- Index

- About the Author