![]()

1 Introduction

Carlos Costa and Dimitrios Buhalis

Anticipating and predicting the future has always been among men’s main wishes. To know what people will like most, and what sort of products and services will be sold and consumed in the future, are key questions that businessmen, politicians, managers and academics would love to have an answer to, if they could. When looking at the way in which tourism will be shaped in the future, there are two dimensions one should take into account. Tourism businesses will undergo major changes as a result of new trends observed in the new emerging consumers. Inevitably new and innovative products will change industry structures and operational requirements. Such a discussion is expanded in the accompanying book entitled Tourism Business Frontiers – Consumers, Products and Industry.

It is on the second dimension of change that this book will be concentrating. The external environment, and the way in which it is anticipated, understood, managed and planned, will decisively influence the success of tourism in the future. Planners, managers, politicians and academics ought to be aware of their external environment and develop techniques and tools to improve their performance. The success of tourism, both at the micro and macro levels, will very much depend on the way organizations and destinations as a whole are planned, managed and marketed.

This book does not deal with the ‘art’ of guessing the future. On the contrary, it attempts to predict the future by using a wide range of trends and scientific methods. Tourism Dynamics: Trends, Management and Tools proclaims that the future of tourism should be predicted through the observation of key trends and indicators. Decision-makers, researchers, academics, politicians, managers and planners can then design and launch suitable tools for improving their competitiveness. The book examines empirical evidence and seeks to provide vision by looking at some of the main trends that are already emerging in society and shaping the future of tourism. The idea that the success of the future tourism industry will depend on the way in which entrepreneurs, politicians and academics understand and explore these changes is right in the heart of the book.

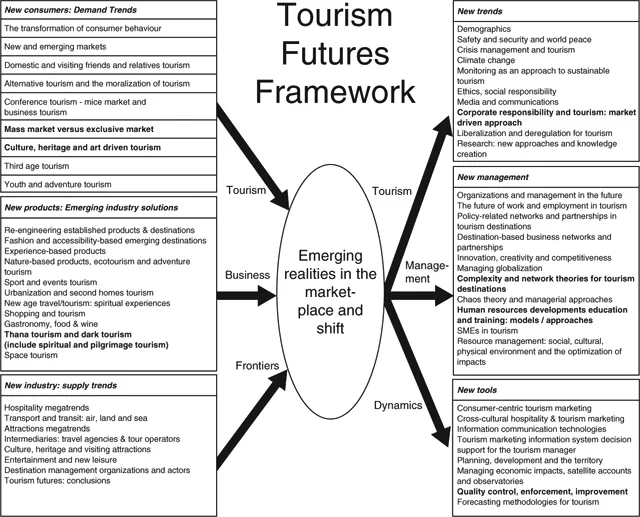

Tourism Management Dynamics also provides an insight into the future management techniques and tools that will be utilized in the tourism industry in order for tourism organizations and destinations to address the emerging trends. This edited publication has been written by some of the most renowned tourism academics and researchers who, based on empirical evidence, analyse past trends, describe the state of the art and provide vision for the future of tourism as it is emerging around the globe. As shown in Figure 1.1, an understanding of the demand and supply trends, as demonstrated in Tourism Business Frontiers, is leading to an appreciation of the emerging realities in the marketplace. Tourism Management Dynamics explores the most significant trends on the external environment, while a number of managerial techniques and tools that will enable tourism organizations to address these challenges are explored. The focus of this book is therefore geared towards explaining the significance of those external environment trends that will shape the future and also towards identifying and discussing suitable management instruments for the future.

Figure 1.1 Tourism futures framework.

One of the central arguments is that the success of future tourism is intrinsically interconnected with the way in which the industry and the tourism system understand and incorporate the emerging critical trends that support its expansion. Tourism is undergoing major changes so far as its demographics are concerned. The ageing of the world’s population and the active lifestyle of older travellers, the emerging new markets, the growing disposable incomes of the youth market and an increasing awareness of the implications of the greenhouse effect, will decisively influence the number, motivations, destination and product choices, as well as activities of future travellers.

Nonetheless, these demographic trends will also be accompanied by major changes in the characteristics of the travel itself. New forms of activities, products, consumption patterns and interaction with both locals and fellow travellers will be observed at the destination areas. Climatic change will also alter the attractiveness of destinations, as temperatures are expected to rise, making Mediterranean destinations for example uncomfortably hot, while affecting the snowfall in alpine regions. Issues related to ethics and sustainability need to be incorporated into the destination planning and management. Safety and security will grow in importance, especially since many terrorism attacks deliberately target tourism honeypots in order to take advantage of international media coverage. Increasingly, destinations and tourism organizations will need to develop crisis management plans to be able to avoid and/or handle disasters. The emerging trends will also be influenced by an increasing visibility of the travel market, which is a result of the globalization of the world media and the transparency that introduces globally. The rapid liberalization and deregulation of markets will bring fierce competition, based not only on price, but also on the quality and the characteristics of the products supplied to clients. These developments will have a strong impact on the way tourism will attempt to capitalize on competitive advantages, by differentiating supply and by offering travellers new, diversified and customer-oriented products.

These new trends will bring profound changes in the management and planning of tourism businesses and destinations. In face of ferocious competition, destinations will need to increase their awareness of the way the industry, processes and systems ought to be analysed and organized. The monitoring of the global tourism system will need to provide information about industry directions, which organizations will need to utilize for developing proactive and reactive responses. Key indicators in important markets should therefore be monitored constantly to provide early warnings about trends and developments in order to trigger both strategic and tactical management mechanisms. Close interaction with research centres, observatories and think tanks will ensure knowledge transfer while it will provide tourism organizations with needed intelligence and strategic tools. Establishing these mechanisms will determine the way in which the tourism industry learns how to plan and react to unforeseen events and also how it may become more innovative, differentiated, authentic and competitive.

As a result, new managerial and planning orientations will gradually be brought into the tourism sector. Increasing competition will require managers to implement new forms of strategic management, capable of maximizing not only direct economic benefits emerging from the operation of individual businesses, but also the optimization of indirect and induced spin-offs that may emerge if a properly networked tourism industry is set up. Contemporary approaches which exploit knowledge, networks, partnerships, SME (small and medium-sized enterprise) clusters and globalization will then emerge. Alongside internal strategies, such as new managerial and organizational approaches, innovation, creativity and learning organizations will also emerge to enhance organizational efficiency and competitiveness. The creation of interconnected and networked regional businesses will be looking for collective competitive advantages within their destinations. They will also strengthen their positioning in the world’s market through competition, i.e. simultaneous collaboration and competition. The globalization of the tourism industry will require not only the expansion of businesses to operate on an international level, but will also demand strategies and tactics that will support businesses and destinations to build their brand and image worldwide.

Academics and entrepreneurs should introduce innovative managerial and planning approaches that will provide the industry with intelligence, knowledge and tools that may bring public and private tourism organizations competitive advantages. Under this wave of development, human resources will also need to gain renewed importance. As tourism is labour (rather than capital) intensive, education and training have to assume centre-stage to prepare the intellectual capacity that will be required for the future. Hence, new directions for tourism education and research need to emerge and mechanisms for closer interaction between academia and practice need to be established.

While global trends push forward new managerial approaches, planners and managers ought to be aware of the emerging tools that will help them to plan, manage and market businesses and destinations. Future trends point towards three strategic directions, namely: satisfying consumers, destination management and territory organization. First, with regard to consumers, tourism marketing will evolve from a classic product-centred approach, to an emphasis placed on tailor-made products that meet the demands of particular niche markets and individuals. Traditional marketing orientations will therefore give place to consumer centred marketing practices, where ultimately organizations aim to please the market segment of one customer. One-to-one (121) marketing will be required in the future. However, to make this financially viable, advanced technology and customer relationship management (CRM) systems, in particular, will need to facilitate the interaction and to ensure that the cost of production and delivery of customized products remains competitive. Meeting, satisfying and exceeding customer’s expectations, while remaining profitable, will be critical for determining the success and the quality of the products provided by the tourism industry. The enforcement and the monitoring of such marketing practices will also be most important to meet forms of sustainable and competitive growth. In an increasingly globalized industry, where both the workforces and clientele are coming from a diverse background, cross-cultural marketing will be significant for the success of both destinations and businesses.

Secondly, along with the new marketing orientations, the success of the tourism industry will depend on the way destinations are managed and planned.The quality of the infrastructures, facilities and amenities assumes critical importance in the way in which consumers are pleased and satisfied and affects the economic benefits for the destination. New planning and development approaches emphasizing regional development, host communities and economic structures of tourism destinations are emerging worldwide. Thirdly, the organization of the territory is increasingly determined by economic forces rather than by formal plans set up by public sector organizations. Driving social and economic forces should be managed within innovative organizational structures capable of bringing together public and private sector organizations. The development of the satellite accounts methodologies and supply side definitions by The World Tourism Organization (WTO), as well as the research undertaken by several observatories that are already flourishing in a number of countries, provide more comprehensive evaluations of the value of tourism and also its impact on national and regional economies. To perform a comprehensive analysis of the impact and contribution of tourism, research tools such as the satellite accounts and forecasting methodologies are required. These will ensure that destinations have scientifically sound approaches for ensuring that they can plan their macro economic benefits based on accurate future predictions. They also have the research tools not only to identify which prospective markets they should target but also to evaluate the economic, sociocultural and environmental impacts of those markets.

The main objective of this book is therefore to discuss future trends of tourism and identify new management and planning tools to enable tourism businesses and destinations to benefit. The book provides an overview of the historical evolution of these areas, so far as knowledge, issues, trends, managerial implications and paradigms are concerned. The ‘state of the art’ is also discussed and emerging trends, approaches, models and paradigms are also introduced. The book provides vision for the future of the tourism industry and analyses emerging and leading practices. Support discussion questions and pedagogic aids and literature are available on the accompanying website to provide further intellectual stimulation and to support additional study and continued pursuit of knowledge.

A companion website containing material for both tutors and students can be found at: http://books.elsevier.com/hospitality?ISBN=0750663782

![]() Part One: New Trends

Part One: New Trends![]()

2 Demography

C Michael Hall

Introduction

Demographics are an important factor in assessing tourism production and consumption. Demography is the study of the characteristics of human populations. This may be done at both a macro level, e.g. in relation to population characteristics in general, or at a micro level, which looks at the characteristics of specific populations either for identified locations or communities or for defined sample populations, such as consumers of particular tourist products, the characteristics of destination residents, or the characteristics of the tourism workforce. Indeed, almost any tourist survey collects the demographic profile of its respondents in order to provide empirical data. The present chapter concentrates on the implications of macro-level demographic data and trends for the future of tourism. However, it also provides an outline of the life-course concept which is central to much discussion of demographic change as well as its implications for tourism consumption.

Demographic theory: from life cycles to life courses

Demography, along with psychographic information, has long been used to assess tourism market trends. Much of the understanding of demographic information, particularly in the western world, has been influenced by ideas that there are normal stages in life through which humans pass and that these stages influence the nature of consumption. These ideas have been most pronounced in the idea of a ‘life cycle’.

As originally conceived, the life cycle referred to individuals moving through certain stages of life, e.g. school, university, work, marriage, children, retirement, at certain ages, and that these stages then influence particular patterns of consumption due to the nature of family and work commitments as well as overall well-being (Glick, 1947). However, such a model has been subject to substantial criticism in recent years. For example, the notion of family life cycle as it was (and still is) usually elaborated, refers to the family circumstances of white urban middle-class Americans in the 1950s and 1960s, which was a far more child-oriented period in the developed world than at present as, since the 1970s the birth-rate in developed countries has slowed substantially (Murphy, 1987).The notion of a family life cycle was therefore time and space specific (O’Rand and Krecker, 1990). Moreover, human life paths are not constituted by the endless repetition of orderly sequences,‘the deterministic implication that life is irreversibly leading something back to where it came from’ (Bryman et al., 1987, p.2); personal time, like historical time, is linear not cyclical. Therefore, attention is increasingly being given to the notion of a life-course perspective.

The life-course approach

The essence of the life-course approach is that the unit of analysis becomes the individual sited in geographical, social, historical and political space and time and that the study of the individual, household or family becomes the study of conjoined or interdependent life courses or paths (Elder, 1994). This perspective suggests that the timing and order of major life events (e.g. partnership (marriage), separation (divorce), birth of children, retirement), be considered with respect to ‘the interplay between individual life stories and population ageing, as well as the relationships among the individual, age cohorts, and the changing social structure’ (McPherson, 1998, p.7). The life course is therefore a social construct.

A life-course approach seeks not to impose a normal or ideal life path as articulated in traditional life-cycle models; instead what is central to the concept of the life course is not the concept of stage but that of transition. Early transitions have implications for later ones with transitions occurring in ‘personal time’, ‘historical time’ and ‘family time’.The life-course paradigm therefore emphasizes that changes in one dimension of the household-ageing process, for example, are necessarily linked to changes in other dimensions. Different personal, historical or societal events create variations within and between cohorts and individuals in the timing and sequencing of events as people age (Nelson and Dannefer, 1992) in different parts of the world. For example, economic depression and war are likely to have substantial impacts on specific age cohorts but not on others, or even on specific individuals within an age cohort depending on specific circumstances. Similarly, McPherson (1998) has noted that the feminist movement has had different impacts on the ageing process throughout the life course for different age cohorts of women, with it having relatively little effect on women who are presently in the later stages of their life but having a substantial effect on age cohorts from the 1970s onwards. Taking a temporal standpoint to analyse behaviour in the life course therefore ‘shifts the focus from static spatial or group-based comparisons of the life course (e.g. current socioeconomic status, residence, education) to more dynamic analysis of the evolving, natural, constructed and data-related aspects of time’ (Mills, 2000, p.93)...