- 396 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

An Introduction to Substructural Logics

About this book

This book introduces an important group of logics that have come to be known under the umbrella term 'susbstructural'. Substructural logics have independently led to significant developments in philosophy, computing and linguistics. An Introduction to Substrucural Logics is the first book to systematically survey the new results and the significant impact that this class of logics has had on a wide range of fields.The following topics are covered:

* Proof Theory

* Propositional Structures

* Frames

* Decidability

* Coda

Both students and professors of philosophy, computing, linguistics, and mathematics will find this to be an important addition to their reading.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

PhilosophySubtopic

Philosophy History & TheoryChapter 1

Introduction

… foundational pretensions have been removed. This allows us to make good use of an idea which may have spectacular applications in the future.

— Jean-Yves Girard, Proofs and Types [99], 1989

1.1 Introducing the Topic

Logic is about consequences. Take a body of propositions. The job of a logic is to tell you what follows from that body of propositions. Sometimes we are interested in consequence relations on propositions “in general.” That is, we pay no attention to the subject matter of the propositions, we pay attention only to the logical relationships between them. This is the traditional scope of philosophical logic. But logic is pursued in other ways too. Sometimes we are interested in particular sorts of propositions — those which have to do with particular structures. We might be reasoning about times or places or processes or some other kind of structure. Logic can be particular. This multiplicity of interests affects the state of logic as a discipline. Logic has a home in philosophy because it studies reasoning with propositions in their generality. But the techniques used in philosophical logic can be fruitfully brought to bear on particular problems, for reasoning about particular structures. This is what makes formal logic useful in computer science (we can reason about processes, functions or actions), theoretical linguistics (we can reason about grammatical structures), mathematics (we can reason about mathematical structures), and other fields.

Substructural logics arise in each of these different fields of study. They apply in both the general and the particular applications of formal logic. As a result, this book should appeal to philosophers, mathematicians, theoretical linguists and theoretical computer scientists. The techniques we will use will draw from each area. Sometimes we will consider abstract accounts of what might follow from what. At others we will reason about (relatively) concrete structures.

Substructural logics focus on the behaviour and presence — or more suggestively, the absence — of structural rules.1 These are particular rules in a logic which govern the behaviour of collections of information. To see why this is important, consider this example. For a wide range of formal systems we have something like this:

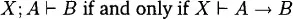

which states that I can validly deduce B from X taken together with A, if and only if I can validly deduce the conditional A → B from X alone. This ties together three important notions. First, validity, which is encoded by the turnstile ‘⊢.’ Second, the conditional, written as →. Finally, there is the mode of premise combination, encoded here by the semicolon. Structural rules dictate the properties of premise combination. Because of the deduction theorem, as premise combination varies, the conditional varies as well. Conversely, if I am interested in different sorts of deduction, then correspondingly I will examine different sorts of premise combination and different conditionals too.

This general scheme has arisen in a number of different areas in logic, motivated by different ideas. I will introduce just three here, leaving more until later.

EXAMPLE 1.1 (RELEVANCE)

Many people have wanted to give an account of logical validity which pays some attention to conditions of relevance. If X ⊢ A holds, then X must somehow be relevant to A. Premise combination is restricted in the following way. We may have X ⊢ A without also having X; Y ⊢ A. The new material Y might not be relevant to the deduction.

In the 1950s, Moh [245], Church [46] and Ackermann [2] all gave accounts of what a “relevant” logic could be. The ideas have been developed by a stream of workers centred around Anderson and Belnap, their students Dunn and Meyer, and many others. The canonical references for the area are Anderson, Belnap and Dunn’s two-volume Entailment [6, 7]. Other introductions can be found in Read’s Relevant Logic [206] and Dunn’s “Relevance Logic and Entailment” [75]. A more polemical introduction and defence of relevant logics can be found in Routley, Plumwood, Meyer and Brady’s Relevant Logics and Their Rivals [231]. (Recent historical investigation by Došen [64] has shown that a basic relevant logic was discussed by I. E. Orlov in the 1920s. However, Orlov’s work was not known to Anderson and Belnap, unlike each of Moh, Church and Ackermann, whose work was explicitly taken up in the Anderson-Belnap tradition.)

EXAMPLE 1.2 (RESOURCE CONSCIOUSNESS)

This is not the only way to restrict premise combination. Girard [96] introduced linear logic as a model for processes and resource use. The idea in this account of deduction is that resources must be used (so premise combination satisfies the relevance criterion) and they do not extend indefinitely. Premises cannot be re-used. So, I might have X;X ⊢ A, which says that I need to use X twice to get A. I might not have X ⊢ A, which says that I can use X once alone to get A. A helpful introduction to linear logic is given in Troelstra’s Lectures on Linear Logic [261].

There are other formal logics in which the contraction rule (from X; X ⊢ A to X ⊢ A) is absent. Most famous among these are Lukasiewicz’s many-valued logics. There has been a sustained interest in logics without this rule [54, 91, 139, 212],

EXAMPLE 1.3 (ORDER)

Independently of either of these traditions, Joachim Lambek considered mathematical models of language and syntax [133, 134]. The idea here is that premise combination corresponds to composition of strings or other linguistic units. Here X; X differs from X, but in addition, X; Y differs from Y; X. Not only does the number of premises used count but so does their order. Good introductions to the Lambek calculus (also called categorial grammar) can be found in books by Moortgat and Morrill [177, 179].

These are three different concerns which motivate different families of substructural logics. In Chapter 2 and in the rest of the book we will see these examples in more detail, and introduce others. One theme of this book is the multiplicity of potential applications of substructural logics. Insights from many different areas will be brought to bear on the topic.

1.2 Introducing the Book

This book is an introduction to substructural logics. It is intended to serve as both an introduction and a reference work to a growing field of logic. It presumes no special knowledge on the part of the reader other than what might be gained from an introductory course in logic. However, further experience in any of mathematics, computing or philosophy will, of course, be helpful.

Each chapter contains exercises, suitable for anyone from a beginner to a doctoral student or researcher in the field. The exercises are designed to draw the reader deeper into the material. Practice questions reinforce concepts introduced in the chapter, problem questions fill in gaps in proofs, extend ideas to analogous contexts and apply results to areas not explicitly covered in the text, and project questions are research projects in their own right. Some of these are problems for which solutions exist in the published literature. Others are, as of the time of writing, open problems. A growing collection of solutions to the problems is available at the Introduction to Substructural logics website:

http://www.phil.mq.edu.au/isl/

This website also contains the errata, and up-to-date bibliographical information, together with links to other resources on substructural logics to be found on the Internet.

The book is divided into five parts. After the introduction, Part I covers Proof Theory, the theory of proofs and deductions, how to put them together and pull them apart. Part II covers Propositional Structures, which are one kind of model for logics, and Part III covers Frames, which are another kind of model. Part IV examines Decision Procedures, the complexity or simplicity of the consequence relations in these logics. Part Y the Coda, considers some philosophical issues arising from the study and interpretation of substructural logics.

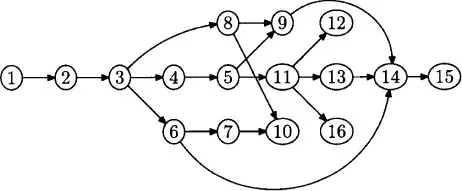

Later chapters depend on earlier ones, but in general, not on all earlier ones. So, there are more ways to use this book fruitfully than the traditional path from start to finish. Figure 1.1 depicts dependencies between chapters. An arrow from n to m means that Chapter m depends on Chapter n.

Figure 1.1: Chapter Dependencies

Most chapters contain Definitions, Examples, Lemmas, Theorems and Corollaries. These are numbered sequentially: Theorem 2.6 is the sixth Definition, Example, Lemma or Theorem (in this case, it is a Theorem) in Chapter 2. So, Theorem 2.6 comes after Definition 2.4 and Lemma 2.5 and before Corollary 2.7. Lemmas, Theorems and Corollaries typically come with Proofs. A proof starts with the word Proof and ends with a box at the right, like this. □

If a statement of a Lemma, Theorem or Corollary e...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half-Title Page

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction

- I Proof Theory

- II Propositional Structures

- III Frames

- IV Decidability

- V Coda

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access An Introduction to Substructural Logics by Greg Restall in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Philosophy History & Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.