- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

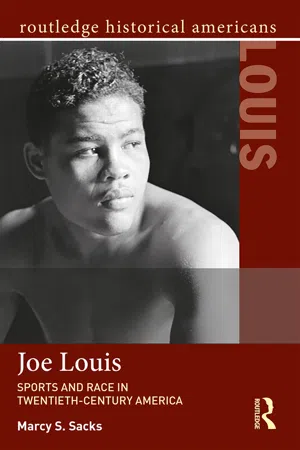

This insightful study offers a fresh perspective on the life and career of champion boxer Joe Louis. The remarkable success and global popularity of the "Brown Bomber" made him a lightning rod for debate over the role and rights of African Americans in the United States. Historian Marcy S. Sacks traces both Louis's career and the criticism and commentary his fame elicited to reveal the power of sports and popular culture in shaping American social attitudes. Supported by key contemporary documents, Joe Louis: Sports and Race in Twentieth-Century America is both a succinct introduction to a larger-than-life figure and an essential case study of the intersection of popular culture and race in the mid-century United States.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Joe Louis by Marcy S. Sacks in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

THE SON OF AN ALABAMA SHARECROPPER

The early part of the twentieth century was not an auspicious time to be black in rural Alabama. Some fifty years after the end of the Civil War, the Old Confederacy had effectively reestablished the racial subjugation of the slave era through exploitative and brutal forms of labor: sharecropping, tenant farming, debt peonage, convict leasing, and chain gangs. The ever-present specter of violence helped to ensure black submission; at least 300 people were lynched in the state of Alabama alone between 1882 and 1922.1 And the combination of crushing poverty and illiteracy destroyed much hope for better prospects in the future.

Into this bleak environment, Joe Louis Barrow was born on the morning of May 13, 1914, “in a sharecropper’s shack off a dirt road that runs between Lafayette and Cusseta in Chambers County, Alabama.” He was the seventh child of cotton farmers living in “red-clay country” in the eastern part of the state “near where Georgia backs into it.” A train depot in LaFayette served as the hub of the cotton economy that thrived in the area despite the hard red clay that local farmers struggled to till. Louis’ father, Munroe “Mun” Barrow, fought to give his family some financial stability despite the difficult conditions; four years before Louis’ birth, he rented a 120-acre farm in an attempt to become upwardly mobile and economically independent. But the workload proved to be too much, and by the time Louis became another mouth to feed, the family worked a far smaller parcel of thirty acres, cultivating cotton and corn and barely eking out an existence. Mun and his wife, Lillie Reese Barrow, welcomed one more child to the family after Joe, and they also fostered an orphaned cousin.2

The eleven of them—Munroe, Lillie, Susie, Lonnie, Eulalia, Emmarell, DeLeon, Alvanius, Joe, Vunies, and cousin Turner Shealey—lived in a cramped, ramshackle wood-framed cabin that looked “like a good wind would have blown it down.” The unpainted structure was typical of sharecropper shacks, with loose boards that sagged and allowed the cold to penetrate almost unimpeded (one of Louis’ strongest memories of his years in Alabama “was how cold I used to get”), no electricity or running water, and no possibility for privacy. The family lit their home with kerosene lamps, and in the darkness the smoky light cast eerie shadows on the walls that made the house look “broody.” Louis also recalled the revelation of discovering indoor toilets after he moved to Detroit; in Alabama, the Barrow family, like all sharecroppers, relied on outhouses.3

True to the relentless pressure to grow ever more cotton, the field backed right up to the cabin, and the agricultural cycle of cotton harvesting dictated the life of the Barrows, as it did for almost all rural blacks in the Deep South. The overriding mission of white landowners in the South’s cotton belt was to ensure the availability of a cheap, abundant, docile labor supply, and even after the fall of slavery in 1865, whites could not conceive of any other productive work for black people than as agricultural laborers working in cotton fields. “The Idea of a Southerner,” admitted a white Tennessee man in a letter to his sister in Massachusetts in 1904, “is to keep the negroes as nere the line of pauperism as is compatibel with self support.” Poverty was essential to black docility. “As long as they are poor they are all right,” he continued, “but as soon as they get some money they get uppity.”4

The sharecropping system virtually guaranteed the inescapability of black poverty. White people owned almost all Southern agricultural land, and black people worked it. The exclusion of black people from other economic pursuits forced the vast majority of them into sharecropping arrangements. Under a standard share agreement, the tenant worked on “halves,” supplying the labor while the landlord provided the land, seed, tools, and work animals. At the end of the harvest, each party received half of the crop. Because the laborer was physically limited in the amount of cotton he could pick at harvest time, the acreage allotments to croppers were typically small—rarely more than thirty acres, as the Barrow family held. And every member of the family was expected to work during the periods of frantic activity: in the planting and hoeing season in the spring and early summer, and the picking season in late summer and early fall.5

Maya Angelou, who grew up in Stamps, Arkansas, in the 1930s, described the physical and mental toll wrought by sharecropping. A long day in the field left workers “dirt-disappointed” as they realized that no matter how large their haul, it would never be enough to free them of debt. They expressed their frustration in grumblings about “cheating houses, weighted scales, snakes, skimpy cotton and dusty rows.” But they kept their complaints within their own community, ever-fearful of whites’ wrath. “I had seen the fingers cut by the mean little cotton bolls, and I had witnessed the backs and shoulders and arms and legs resisting any further demands,” Angelou wrote. And it filled her with “inordinate rage.”6

Louis vividly recalled his own family’s experience with sharecropping. Although he was too young during the majority of his years in Alabama to participate in the most grueling tasks, he remembered that his older brothers and sisters joined their parents in the fields each morning at sun-up and stayed out all day until sundown. Joe had chores around the house to perform, including feeding the chickens and hogs and cleaning the house. On hot summer days, the boy would fill a bucket with cool water from the well and haul it out to his family members in the cotton fields where they would gratefully drink from a long tin dipper. During the peak picking season, even the young Louis would be commandeered for work; every hand had to contribute in order to make the harvest successful. Most nights, the family went to bed early, the result of both sheer exhaustion and the need to be ready to do it all over again the next day.7

Under this exploitative system, the essential socioeconomic patterns of antebellum agriculture persisted. At the end of each season, sharecroppers routinely discovered that their portion of the harvest did not yield them enough money to ever escape poverty or to lay away savings. “It was pretty bad with the poor man in the South,” observed Turner Shealey, the Barrows’ cousin. “All of us had to obligate ourselves to the merchants to get a livelihood. We had to be subservient to get sufficient funds to operate a crop.” White people had tremendous control over black people’s lives. If “you didn’t do what you shoulda did,” Shealey continued, whites would “take everything you had—all the crop; the foodstuffs you had grown in the garden; your animals such as hogs, mules or cows; the farmer’s tools—and you had to move away from his plantation and go obligate yourself with somebody else.” The Barrows often struggled to produce enough crop each year, and Shealey remembered that they had to move often.8

Conditions like those endured by the Barrows meant that the great mass of Southern black laborers remained tied to the land as a propertyless peasantry, dependent on white people, and relegated to a nearly unbreakable cycle of poverty and ignorance. Violence, or the threat of violence, guaranteed the perpetuation of this debt-labor system just as it had during the slave era, and corruption or the acquiescence of local officials was openly tolerated. Whippings on plantations continued unabated as a replication of slave-era punishments. An Alabama legislator defended the practice in 1901: “Everybody knows the character of a Negro and knows that there is no punishment in the world that can take the place of the lash with him.”9

Even worse than the punishments that harkened back to the antebellum era was the rampant persistence of unfreedom throughout the South. The nefarious practice of ensnaring black people into a web of debt peonage and convict leasing haunted every black person toiling in the South. Any black person who ran afoul of the law, either legitimately or on any number of fabricated charges, might find himself thrust into the dark, impenetrable underworld of convict leasing that spurred the New South’s industrialization and functioned almost unimpeded until World War II. Through spurious claims of criminal activity, tens of thousands of random, innocent black people found themselves caught up in the dragnet, seized on largely arbitrary grounds, and hauled hastily before provincial judges, mayors, or justices of the peace who often held economic interests in the businesses employing convict lessees.10

By 1903, Alabama had become the peonage capital of the nation, and convict leasing fueled the growth of the coal industry centered near Birmingham. Perpetrators of the system survived a rash of legal challenges brought by federal investigators during a short-lived moment of concern. Despite judicial rulings that struck down state laws creating peonage, federal officials lacked the tools and the will to enforce those decisions. Investigators retreated and the architects of the program became further emboldened. A new state constitution adopted in 1901 effectively stripped black Alabamians of the franchise, making them powerless to mitigate the rampant use of forced labor. At the constitutional convention in the state capital, one white delegate brazenly declared, “I believe as truly as I believe that I am standing here that God Almighty intended the negro to be the servant of the white man.”11 This brutal system of involuntary servitude terrorized black people throughout the South and made them into “slaves in all but name.”12 As historian Douglas Blackmon has explained, “A world in which the seizure and sale of a black man—even a black child—was viewed as neither criminal nor extraordinary, had reemerged. Millions of blacks lived in that shadow—as forced laborers or their family members, or simply as people who heard the whispers of hidden terrors and lived in fear of the system’s caprice.”13

The pressure of raising and providing for a family, to preserve one’s dignity, and to not succumb to utter hopelessness under these conditions proved to be too much for some black people, including, apparently, Joe Louis’ father. Munroe Barrow was a tall, lean man measuring over six feet tall and weighing just shy of two hundred pounds. According to his wife, Lillie, he “wanted to be a good family man” and provide the best for his wife and children. But the “strain and hard work was too much for him,” and he was intermittently hospitalized for mental illness during a ten-year stretch that began in 1906. In 1916, two years after Louis’ birth, Mun was finally committed permanently at the Searcy Hospital for the Negro Insane in Mt. Vernon, Alabama. “I guess it makes a man feel bad not to be able to give his family more,” Louis observed laconically, “especially if you can see beyond the cotton balls and those hard red hills.”14

Left alone with nine children, the youngest still under a year old, Lillie confronted the daunting challenge of providing for her family. Fortunately, she had the fortitude for the prodigious task. Lillie Reese was born in Chambers County and, according to her famous son, knew how to work “as hard, and many times harder, than any man around.” Her determination meant that the family continued to produce a crop every season despite the absence of an adult man. “She could plow a good straight furrow, plant and pick with the best of them—cut cord wood like a lumberjack then leave the fields an hour earlier than anyone else and fix a meal to serve to her family,” Louis declared with admiration. During the episodes of Mun’s temporary hospitalizations, she managed the family and fields on her own, and after he was permanently institutionalized, the strong, five-and-a-half-foot woman spent a number of years coping alone with the tremendous responsibility of feeding nine hungry children and keeping the family intact. The Barrows also had the support of a strong community, and while the neighbors “were real poor people,” they nevertheless helped out in myriad small ways. Some people gave bits of change to the young Barrow children; others shared their food “when the crops didn’t come through like they should.”15

But times were hard, and Lillie took another husband sometime around 1920. Pat Brooks came to the marriage as a widower with eight children of his own (five still living at home), and Joe became very close with his stepbrother, “little Pat.” The two were the same age and “kept happy” by spending much of their time together when the older children worked in the fields. The boys played in the cotton and rode atop the huge pile as the crop was hauled to the cotton gin in Camp Hill, where the two watched, enthralled, as the machine sucked it off the wagon. “The mul...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-Title

- Series

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 The Son of an Alabama Sharecropper

- Chapter 2 “Born with Two Strikes”

- Chapter 3 “The Man in the Mask”

- Chapter 4 “Heroes Aren’t Supposed to Lose”

- Chapter 5 “A Credit to His Race”

- Chapter 6 “It Makes Us a Pack of Liars”

- Documents

- Bibliography

- Index