![]()

CHAPTER

1 Producing: Exploiting New Opportunities and Markets in the Digital Arena

• What new markets and opportunities has the digital area fostered?

• Why are distribution and exhibition so important to the production process?

• What effect does the audience have on the production process?

• What are the chief means of exhibiting media productions?

• How does the economics of a production and distribution affect the content?

• What systems will be used to distribute and exhibit media in the future?

Introduction

The new world of advanced digital media production abruptly appeared in the studios, editing suites, radio and TV operations, independent production operations, and film studios with a suddenness that caught most people in the media production business by surprise. At first, digital equipment and technology appeared at a steady pace, bringing smaller equipment, lower costs in both equipment and production methods, and surprising higher quality. Then the Internet, originally considered as a supersized mail system, became a practical means of distributing all forms of media—audio, video, graphics—at a low cost and within reach of anyone with a computer and an Internet connection. Because of the two factors of low cost and accessibility, most concepts of media production distribution, and exhibition had to be reconsidered and restructured for producers to remain competitive, gain funding for productions, and reach targeted audiences.

This chapter considers the relationship of the audience to distribution of productions, the changing technologies of distribution and exhibition, the economics of distribution, and the future of exhibition.

THE AUDIENCE

Audience Analysis

An accurate estimate of the size, demographic makeup, and needs of a prospective audience is essential for the development of workable funded projects and marketable media ideas. What media should a producer use to reach a specific audience? How large is the potential audience? What size budget is justified? What needs and expectations does a particular audience have? What television, film, or graphics format should be used? These questions can only be answered when the prospective audience is clearly defined. Even in noncommercial productions, the overall budget must be justified to some degree on the basis of the potential size and demographics of the audience:

Audience Analysis

• Choice of medium

• Size of audience

• Budget justification

• Audience expectations

• Choice of medium format

Audiences differ in size and demographics. The age and gender of the members of an audience are often just as important as the overall number of people who will see the production. Television advertisers, for example, often design television commercials to reach specific demographic groups. Even documentary filmmakers, such as Michael Moore who produced the documentaries Sicko and Bowling for Columbine, often pretest films on audiences to see how effective they are in generating and maintaining interest and waging arguments. The process of assessing audience preferences for and interest in specific projects has become more scientific in recent years, but it inevitably requires an experienced and knowledgeable producer to interpret and implement research findings:

Audience Demographics

• Age

• Gender

• Income

• Education

• Religion

• Culture

• Language

Detailed audience information can facilitate later stages of the production process by giving the audience input into production decisions. The nature and preferences of the audience can be used to determine a project’s format, subject matter, and structure, as well as its budget. For example, the reality series Survival (2007) was targeted specifically for working-class families interested in outdoor-adventure dramas. Everything from the actual locations to specific character types was selected on the basis of audience pretesting. While the artistic merit of using audience-survey research to make production decisions may be questionable, since it can produce a hodgepodge of styles and content rather than a unified work, its success has to some degree validated the technique in the commercial marketplace. It has also proved vital for noncommercial productions, where audience response is a primary measure of program effectiveness. Research can also be used during postproduction to assess the impact and effectiveness of a project. While audience research is no substitute for professional experience, it can give scientific, statistical validity to production decisions that might otherwise be based solely on less reliable hunches and guesses.

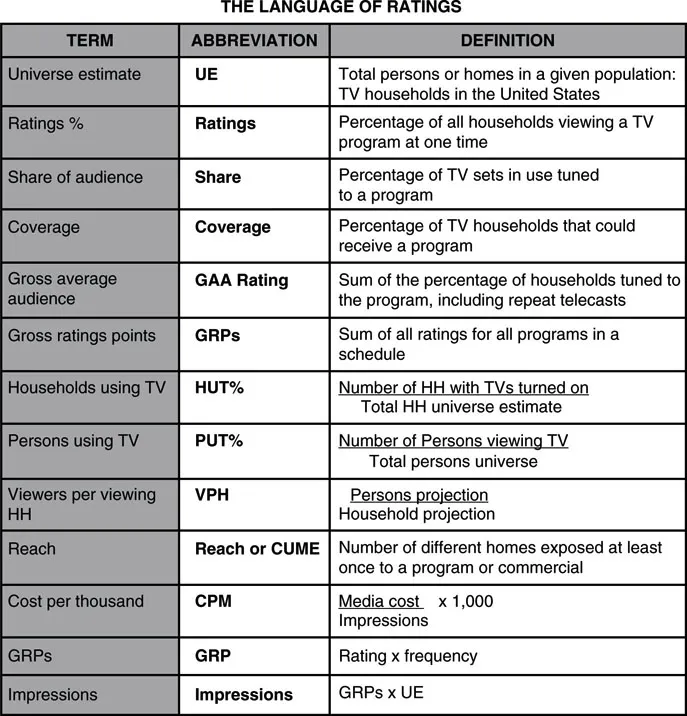

Estimating the size and demographics—for example, the age, gender, and other characteristics, of the potential audience for a prospective media project—can be quite complicated. Sometimes a project’s potential audience can be estimated from the prior success of similar productions. For example, producers can consult the A.C. Nielsen and Arbitron ratings for television audiences drawn to previous programming of the same type. Television ratings provide audience information in the form of program ratings, shares, and demographic breakdowns for national and regional television markets. Ratings or rankings refer to the percentage of all television households—that is, of all households with a television set regardless of whether that set is on or off at a particular time—that are tuned to a specific program. If there are 80 million television households and 20 million of them are tuned to a specific program, then that program has a rating of 25, which represents 25 percent of the total television population.

Shares indicate the percentage of television households with the set turned on at a specific time that are actually watching a specific program. Thus, if 20 million households are watching something on television at a particular time and 10 million of those 20 million households are watching the same program, then that program has an audience share of 50, which represents 50 percent of the viewing audience (Figure 1.1).

FIGURE 1.1 The terminology used by programmers and salespeople in broadcast media is a language of its own. The terms are both descriptive and analytical at the same time, but they are meant for professionals in the field to be used for accurate and concise communication.

Methods of determining audience value on the Internet is made easier by the system of counting the number of times a web site has been opened, or “hit,” in a search. The hits provide an exact count of the number of times an audience has opened a site, but it does not tell how often they stayed to read or comprehend what was shown on the site. The method measuring hits is more accurate than ratings, but it is still not an absolute measurement of audience reaction—pleasure or displeasure. A new measuring system, the Total Audience Measurement Index (TAMI) is in development to include an audience’s participation in all media simultaneously—broadcasting, cable, satellite, Internet, and mobile use—as a total research value.

Commercial producers and distributors often rely on market research to estimate audience size and the preferences of audiences that might be drawn to a particular project. The title of the project, a list of the key talent, the nature of the subject matter, or a synopsis of the story line, for example, might be given to a test audience, and their responses are recorded and evaluated. Research has shown that by far the best predictor of feature film success is advertising penetration—that is, the number of people who have heard about a project—usually through advertising in a variety of media. Other significant predictors of success appear to be the financial success of the director’s prior work, the current popularity of specific performers or stars, and the interest generated by basic story lines pretested in written form.

Audience research has been used for a variety of purposes in commercial production. Sometimes before production, researchers statistically compare the level of audience interest (the “want-to-see” index) generated by a synopsis, title, or credits of a production to the amount of audience satisfaction resulting from viewing the completed project. A marketing and advertising strategy is often chosen on the basis of this research. A film that generates a great deal of audience interest before production, but little audience satisfaction after viewing a prerelease screening of the completed film, might be marketed somewhat differently from a film that generates little interest initially but is well received in its completed form. The former might be marketed with an advertising blitz and released to many theaters before “word of mouth” destroys it at the box office, while the latter might be marketed more slowly to allow word of mouth to build gradually.

Some television programs and commercials will be dropped and others aired solely on the basis of audience pretesting. Story lines, character portrayals, and editing are sometimes changed after audience testing. Advertising agencies often test several versions of a commercial on sample audiences before selecting the version to be aired. A local news program may be continuously subjected to audience survey research in an attempt to discover ways to increase its ratings or share. A sponsor or executive administrator may desire concrete evidence of communication effectiveness and positive viewer reaction after a noncommercial production has been completed.

Audience research has to be recognized as an important element in the production process. While it is no substitute for professional experience and artistic ability, research nonetheless can provide some insurance against undertaking expensive projects that have no likelihood of reaching target audiences or generating profits.

Noncommercial audience research often focuses on assessments of audience needs and program effectiveness. A project that is not designed to make money often justifies production costs on the basis of corporate, government, or cultural needs as well as audience preferences and size. Sponsors need to have some assurance that the program will effectively reach the target audience and convey its message. Audience pretesting can help to determine the best format for conveying information and reaching the audience. Successful children’s programs are often based on audience research that assures program effectiveness. For example, the fast-paced, humorous instructional style of Sesame Street, which mirrors television commercials and comedy programs, was based on exhaustive audience research. Whether it is used during preproduction or postproduction, audience research can strengthen a program and widen its appeal.

THE TECHNOLOGY OF DISTRIBUTION

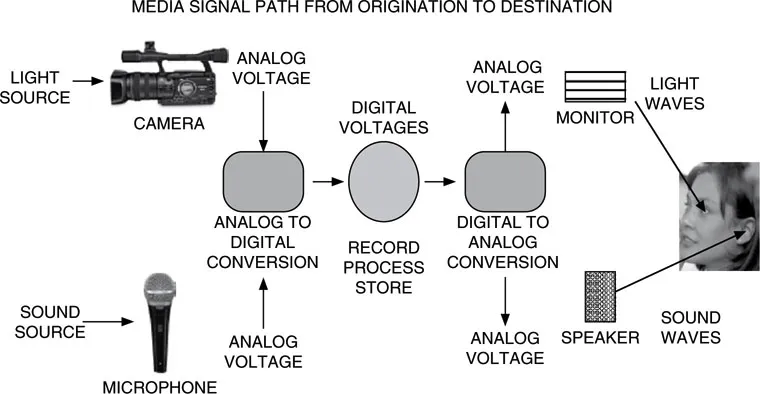

Media production requires both analog and digital technologies. The advent of digital technologies stimulated a number of important changes in media production, including the convergence of technologies as well as corporate integration. The digital revolution describes a process that started several decades ago. Technicians developed uses for the technology based on “1” and “0” instead of an analog system of recording and processing audio and video signals. Rather than a revolution, it has been an evolution, as digital equipment and techniques have replaced analog equipment and processes where practical and efficient. Digital equipment may be manufactured smaller, requiring less power, and producing higher-quality signals for recording and processing. As a result, reasonably priced equipment, within the reach of consumers, now produces video and audio productions that exceed the quality of those created by professional equipment of less than two decades ago. But it must be remembered every electronic signal begins as an analog signal and ends as an analog signal, since the human eye and ear cannot directly translate a digital signal (Figure 1.2).

FIGURE 1.2 All sounds and light rays are analog signals as variations in frequency from below 60 Hz as sound to a range above 1 MHz for light. Any frequency may be converted to a digital signal duplicating the original analog signal, but for humans to be able to see and hear an audio or video signal it must be converted back to an analog signal.

The signals that create light and sound are analog signals. The types of equipment that make up optics in lenses and cameras, physical graphics, sets, and the human form all exist as analog forms. The signals a camera and microphone must convert from light and vibrations to an electronic signal must be an analog signal first and then may be converted to a digital signal. At the opposite end of the media process, a human cannot see an image or hear sound as a digital signal but must wait for the digital signal to be converted back to analog to be shown on a monitor and fed through a speaker or headset.

Communication production systems now move from the analog original to a digital signal, not a digital rendering of a video or audio signal, but straight to a pure digital signal without compression or recording on any media such as tape or disc. The analog of the light and sound need not be converted to a video, audio, film, or graphic signal but may remain as a digital stream until converted back to analog for viewing and or listening. All acquisition, storage, manipulation, and distribution will be in the form of a simple digital signal. Digital systems obviously will continue to improve from 8-16-32-64-128 bits as storage and bandwidth factors improve and expand. The number of bits indicates the level of conversion to a digital signal. The higher the bit rate, the better the quality of the digital signal, although the higher bit rate also requires greater bandwidth for storage and for transmission during distribution.

Tape will slowly disappear as the primary means of recording, distribution, and storage of media systems before discs and film disappear as a useful and permanent medium. Some forms of tape recording for high-end cameras will continue to be used to record digital, but not visual or aural signals that are then fed directly to postproduction operations. The lifetime of discs also may be dated as solid-state recording media such as P2 and other flash-type drives increase their capacity and costs decrease.

NEW PRODUCTION CONSIDERATIONS

Today production personnel may take advantage of the digital evolution to change the production technologies now available as well as the increased range of the methods of distribution of media productions. Production and distribution methods now must be considered together or the value of the production may never be realized.

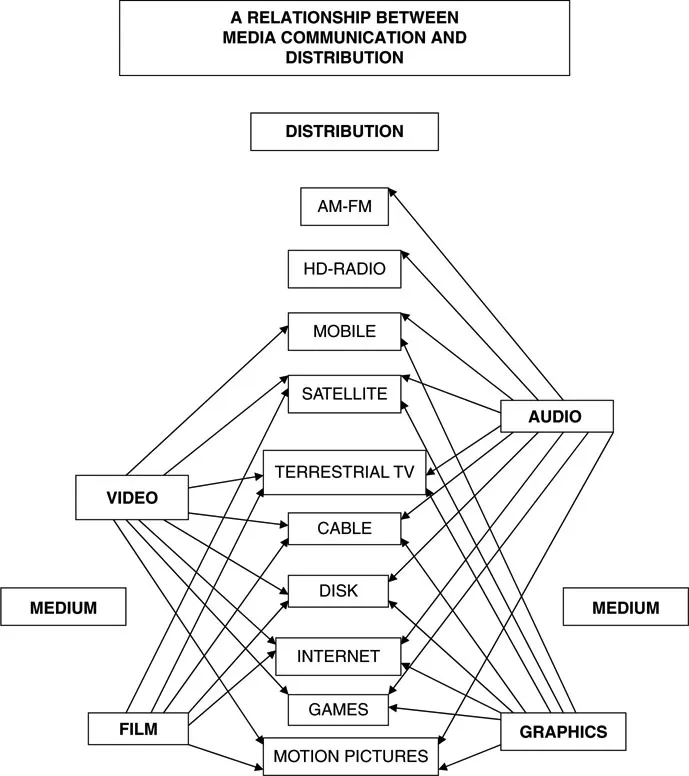

Digitized signals of any media production now may reach an audience in almost infinite different paths of distribution. The traditional mass communication systems of radio-TV-film, cable, and satellite now are joined by digital signals distributed via a vast number of new systems by means of the Internet and Web variations now joined by mobile systems of podcasts, cell telephones, and other handheld computers (Figure 1.3).

FIGURE 1.3 The relationship between the many possible media distribution forms and the communication media production formats indicate an interlocking relationship that is neither linear nor hierarchical.

Instead of media distribution via terrestrial radio and television broadcasts, cable, and motion pictures, the ubiquity of wireless digital signals distributed via WiFi, WiMax, and other “open” distribution systems has necessitated changes in media production theory, methods, technology, distribution, and profit sources. Digital production methods and operations are covered in Chapter 2.

There are four areas of consideration that must be contemplated to make key decisions between the birth of the original production concept and the first rollout of equipment:

• Which distribution method will be used?

• Which production format will be used?

• Which electronic media will be used?

• Which genre will tell the story best?

THE BIG TEN OF DISTRIBUTION

AM-FM Terrestrial Radio

Terrestrial radio programming consists of music, news, public affairs, documentaries, and dramas, programming aimed at the largest possible audience. Except for public radio there is very little niche or specialized programming on standard radio channels. Terrestrial radio includes high-definition (HD) digital radio along with traditional analog radio, now often simulcast together...