- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Regional Dimension of Transformation in Central Europe

About this book

Providing a new picture of the socio-economic map of central Europe after several years of transformation, and focusing in particular on Poland, this book gives an account of the major problems of regional restructuring. The author identifies the opportunities and problems faced by particular regions by relating the Polish experience to the experience of other central European countries. This in turn provides a general picture of spatial patterns of transformation in this specific part of Europe and will interest those concerned with the transformation of Eastern Europe.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Regional Dimension of Transformation in Central Europe by Grzegorz Gorzelak in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Urban Planning & Landscaping. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

The General Processes of Transformation – An Overview

General Course of Central European Reforms

The post-socialist countries of Central Europe have begun their economic, political and social transformation with a heavy burden of socialist heritage. This heritage was not entirely of a negative character. Obsolete production structures, relatively underdeveloped technical infrastructure, low level of technological, organisational and managerial advancement, and closeness of economies could be mentioned as the most important negative features. However, these countries have demonstrated a relatively well educated – though to a great extent demoralised – labour force, a higher level of social security and development of social infrastructure than could have been ascertained only from the ‘pure’ level of economic development.

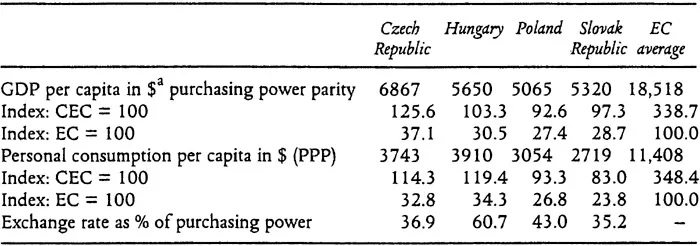

In any case, in comparison with the West the Central European countries occupy the lowest positions (see Table 1.1). The economic reforms which were introduced in these countries assumed different models of development. In Poland changes in the national economy implemented since January 1990 followed the pattern of a shock therapy, which resulted in deep recession and breakdown of several branches of the Polish economy. In fact, it was only very recently that the first signs of its positive effects could be seen.

Table 1.1 GDP level compared to the European Community in 1992

Note: | a the numbers presented in the table are estimated by each country on the basis of the 1990 ICP comparisons; preliminary direct results of the ICP 1992 are the following: Czech Republic $7925, Hungary $6685, Poland $4710, Slovakia $5850. |

Source: | Gorzelak et al. (1994) Table 8. |

Poland was unique in this respect among other post-socialist countries. As specified in the economic part of the report on the future of Central Europe (Gorzelak et al. 1994):

Various approaches were chosen, ranging from the Polish ‘Big bang’ ap- proach (a drastic anti-inflationary program combined with a fast liberalisation of the economy) through less radical and more pragmatic former Czechoslovak program until the most cautious Hungarian macroeconomic policy of a ‘soft landing’ in capitalism. Such a choice was also due to differences in the starting point for the reforms: Poland, with its hyperinflation and huge macroeconomic imbalances was not able to choose a slower, but less risky Hungarian or Czech road. A different situation occurred in the approach to privatisation. This time it was Czechoslovakia (and then the Czech and Slovak Republics) that was forced to choose the most radical, but also the most risky ‘Big bang’ (the voucher privatisation). Poland and Hungary, with their rapidly expanding private sectors and relatively well developing capital markets were able to introduce much more deliberate policies. In Hungary the application of the ‘Big Bang’ approach would not have been justified, since the transition was prepared in many respects and inflation was held under control.

The problems that all the countries had to face also depended on their relative starting points. However, in spite of initial views, a strong likeness emerged in the pattern of economic problems being experienced. All the CEC economies have suffered a major drop in levels of output (in the state-owned sector), growing unemployment, and strong inflationary pressures. The collapse of the COMECON trade has led to a dramatic decrease in their exports to the Eastern markets.

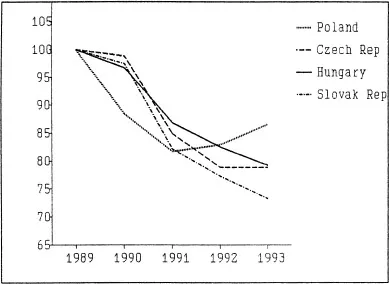

During 1992, almost all of a sudden, Poland assumed the role of a leader in economic transformation among European post-socialist countries. This was due to several positive processes and phenomena, explored in more detail in the sections below. Being the first country to take the transformation path, Poland was also the first to pay economic and social costs incurred as a result of this process. However, Poland was also the first to show signs of economic recovery. 1992 was the first year which did not bring further decline of overall economic output and the increase of the GDP reached 2.2 per cent, rising to 4.5 in 1993 and to 5% in 1994. In this respect Poland appeared to be unique among all other post-socialist countries. Figures 1.1 and 1.2 present the comparison of economic performance of the post-socialist countries during the 1990s.

Figure 1.1 GDP index for Central European countries (1989=100)

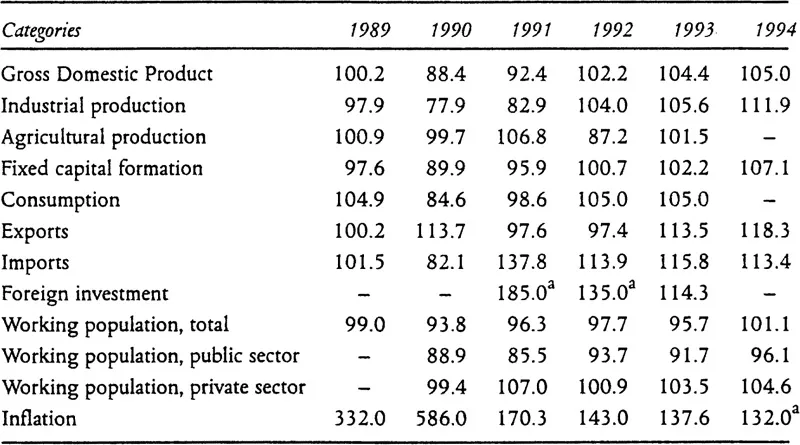

Table 1.2 presents the dynamics of major economic categories in Poland during the transformation period.

Table 1.2 Dynamics of basic economic categories, Poland, 1989–1993, previous year = 100

Note: | a) rough estimate – no precise data available |

Dynamics of industrial production of Poland in 1992 presented an upward trend since March/April. This trend was reflected in an overall growth of industrial production in 1992 and then accelerated growth in 1993 (to reach 107.4% of the 1992 level), further prolonged during the first months of 1994, when industrial production grew by more than 10 per cent in relation to the same period in 1993. However, by the end of 1993 industrial production reached only 75 per cent of the 1989 level, which shows the depth of the recession as measured by official statistics (it should be assumed that real recession was smaller, since the ‘grey economy’ grew substantially after 1990).

The housing sector is in an especially dramatic situation. 1993 was the 15th consecutive year of decline in the number of newly constructed dwellings, dropping in 1993 to 65 per cent of the 1992 level. In general, the number of dwellings completed has fallen to mid-1950s levels. On the other hand, the output of the entire construction sector is consistently rising, demonstrating an upward drive in capital investment.

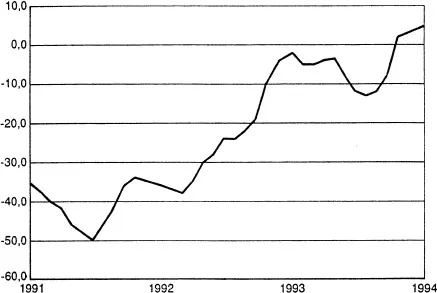

Figure 1.2 presents evaluations of enterprises of their overall performance (replies received from 1240 industrial enterprises accounting for 22% of total industrial employment). They are systematically asked about the dynamics of their production. Since mid-1991 the upward trend is clearly visible, though as late as the end of 1993 there were more enterprises which noted growth in production than were still on a downward curve. More in-depth analyses reveal that the firms which operate in more dynamic branches are evaluating their situation as improving. A more ‘optimistic’ outlook is also presented by bigger enterprises, which is an interesting observation, contradicting generally held beliefs on the low effectiveness of state-owned giants (this may be, however, influenced by the relatively stronger position of big enterprises and some indirect support of the state).

Source: Instytut Rozwoju Gospodarvego, Szkola Glowna Haudlowa 1993

Figure 1.2 Business cycle in Polish industry in enterprises’ opinions

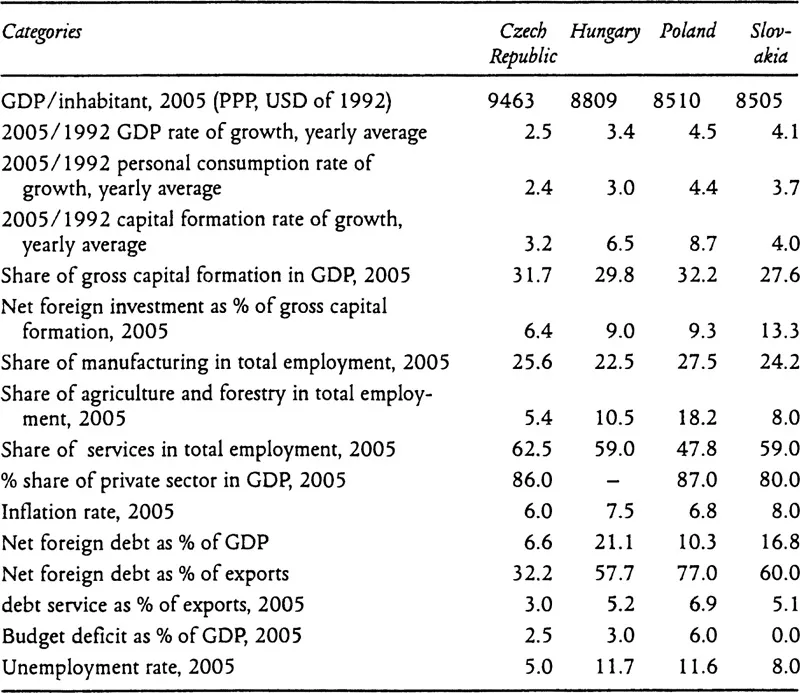

In general terms, the other three Central European countries are beginning to demonstrate the first signs of recovery too. For example, in Hungary during the second quarter of 1993, industrial production reached positive dynamics (growth at the rate of 5% compared to the same period in 1992). In 1993 the GDP fell in Hungary by only -1 per cent and in 1994 it grew by 2 per cent. However, stable positive growth of the entire economy is envisaged as late as 1997. The Czech economy is recording similar results (decline of the GDP only 0.5% in 1993 and growth of 3% in 1994). In Slovakia the situation is rather more complex, since in 1993 this country had the greatest (among the four countries) decline of the GDP, equal to -4.7 per cent and also in 1994 this category fell by 2 per cent. 1995 ought to be the first year when the further decline of the Slovak economy is halted. Table 1.3 presents the most optimistic development which might happen in the four Visegrad countries until the year 2005 (according to the prospects formulated by the international experts within the ‘Eastern and Central Europe 2000’ project).

Table 1.3 Economic development of Central European countries, 1992–2005

Source: Gorzelak et al. (1994)

A cumulative effect of the official GDP decline during the period 1989–1993 is as follows: Poland, -15 per cent; Hungary, -21 per cent; Czech Republic, -21 per cent; Slovakia, -28 per cent. Due to rapid growth of the ‘grey economy’, actual decline has been lower by a few percentage points. In any case, Central Europe presents much better results than other post-socialist countries (for example, the decline of the GDP in the same period amounted to 45% in Russia, 41% in Bulgaria, 40% in Albania and 37% in the Ukraine).

In all Central European countries agriculture has been the sector most exposed to foreign competition, which the Central European agriculture had to lose. In Poland this was due to its ineffectiveness and subsidies paid to producers of food in countries exporting their agricultural products to Poland. Overproduction of food (in relation to domestic demand) had already emerged in 1990 and was aggravated by a good harvest in 1991. As a result, farmers withdrew from increasing production, which is reflected in data for 1992. This drop was also due to an almost total collapse of large state-owned agricultural enterprises. In effect, farmers were the socio-professional group which lost most during the transformation. In other Central European countries, where agriculture used to be entirely collectivised (i.e. remained either in the hands of the state or constituted co-operative ownership), the problems of agricultural organisation relied on both adjustment to smaller demand and changing the structure (in Poland this last factor affected only some 25% of agriculture).

In general, the economic situation of the four Central European countries in 1992 can be presented in a very concise form in Figure 1.3. The Czech economy is the most balanced, but the least dynamic. Poland p...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Tables

- List of Figures

- Introduction

- Chapter 1. The General Processes of Transformation –An Overview

- Chapter 2. The Historic Heritage of Socio-Economic Space

- Chapter 3. The Regional Patterns of Transformation

- Chapter 4. The Regional Potential for Transformation

- Chapter 5. Regional Policies

- Index