- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Evolution of Social Networks

About this book

This book answers the question of whether we can apply evolutionary theories to our understanding of the development of social structures.

Social networks have increasingly become the focus of many social scientists as a way of analyzing these social structures. While many powerful network analytic tools have been developed and applied to a wide range of empirical phenomena, understanding the evolution of social organization still requires theories and analyses of social network evolutionary processes. Researchers from a variety of disciplines have combined their efforts in what is an indication of some very promising future research and the work represented in this volume provides a basis for a sustained analysis of the evolution of social life.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Evolution of Social Networks by Patrick Doreian,Frans Stokman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

THE DYNAMICS AND EVOLUTION OF SOCIAL NETWORKS

PATRICK DOREIAN

FRANS N. STOKMAN

This volume is predicated on two very simple assumptions: there is a need for explicit dynamic social network models and the social networks community is ready for them. Indeed, there are some dynamic models available already. The contributions contained in this volume build on the earlier research and are intended to contribute to, and extend, those lines of work. Our introduction starts with the twin ideas of structure and process and moves to a characterization of network dynamics and the evolution of social networks.

1. SOCIAL STRUCTURE AND SOCIAL PROCESSES

While it seems straightforward to define, and describe, social network structures, the task of describing social network processes is much harder. Moreover, attempts to model these processes create many difficult technical problems. We discuss some of these and emphasize that we have constrained our discussion in consequential ways. First, we focus on empirical issues. Obviously, this includes the idea of data analysis for observed network phenomena, but we extend the term to include the generation of simulated data based on theoretical models. Second, we are concerned with explicit formal models. These can take the form of mathematical representations and/or algorithmic statements of process rules. While purely verbal formulations provide valuable insights into network processes and are a rich source for ideas, they remain outside the scope of this discussion.

1.1. Structures

The simplest, and most fundamental, definition of structure is a set of social actors with a social relation defined over them. A small group of “people” and the relation “friendship” and social service organizations with the relation “referring clients” provide two examples. This definition of structure has been extended in several directions. One is to consider multiple relations for a set of social actors. Continuing the inter-organizational example, the additional relations could be “provides services”, “coordinates”, “sends money” or “provides political support”. The Bank Wiring Room data (Roethlisberger and Dickson, 1939; Homans, 1950) is a widely used and cited network with multiple relations that include friendship, antagonism, playing games and helping. As far as representational tools are concerned, graphs can be used for a single relation and multigraphs or hypergraphs can be used for multiple relations.

A second fundamental type of relation is “membership” where social actors belong to two distinct types that are mapped to each other under an inclusion rule. Two example are individuals belonging to friendship groups and individuals on organizational boards. For the latter, individuals as directors belong to organizational boards. Breiger (1974) provides an elegant discussion of the “duality” between people and groups. The analyses of these (two mode) data structures involve the membership tie plus two ties that can be generated from it: (1) a collectivity-to-collectivity relation and (2) an individual-to-individual relation. Using the director-board example, there is a relation over the directors (joint membership) and one over the companies (shared directors).

A related, but distinct, idea is one where there are multiple levels for a network. If we think of people and friendship groups, the set of network ties among the individuals belonging to these groups can be aggregated to form relations between the groups. Or, as another example, people working for social service agencies have many social ties among themselves (as representatives of their agencies) that, when aggregated, generate relational ties between their organizations. This can be expanded into a systematic effort to understand the “micro-macro relationship” where there are distinct relations among the actors at each level. The processes at the two levels are assumed to be coupled. Representing and understanding the dynamics of this coupling of relations is a non-trivial task.1

Another extension comes if we think of networks as networks of networks (Wellman, 1988). If societal sectors are institutionalized (Scott and Meyer, 1991), then an inter-organizational network could be represented as a network of organizations within sectors that are then linked in some fashion. Or, if the focus is on the provision of services, different client pools define networks of organizations serving people in those pools. Then, for multiple problem clients, these specific networks are linked into a broader network. Put differently, networks can be nested within broader networks. This becomes complicated if the nesting and aggregation aspects are intertwined with the aggregated ties differing from, and not mapping cleanly to, the nested ties. But even with this difficulty, the task of describing structure is simply one of defining social actors, defining the relevant social relations and describing them with some appropriate tools.

1.2. Processes

Social network processes seem more elusive for formal model building. In part, this stems from the simple idea that structures seem easier to observe: we can take snapshots at specific moments in time. To get at the idea of social network processes, we look closely at each term. We start with the idea of process. It is instructive to consult a dictionary.2 Consider the following three definitions of a process: (1) “a series of actions or operations used in making or manufacturing or achieving something”; (2) “a series of changes” and (3) “a course of events or time”. Next, Lenski et al. (1991: 438–9), in their text on human societies, define the term “social” as “having to do with relationships among the members of societies”. This points towards a network representation and we have already defined the term network. Lenski et al. view process as “a series of events with a definable outcome”. By linking these ideas, we view a social network process as a series of events involving relationships that generate (specific) network structures. More glibly, network processes are series of events that create, sustain and dissolve social structures.

Clearly, any network structure can be defined formally — we can use any of the tools used to “describe” structure — and so have a “definable outcome”. Assembling a series of descriptions of structure through time will satisfy the second meaning of “process”. This seems an important step as we are compelled to look at networks with a through time perspective. In one sense, the last two dictionary meanings of process are the same. However, we will draw the following distinction and view a “course of events” as having some coherence. Events at one point in time are conditioned, in part, by the events that went before them: networks evolve. Specifying how this occurs — and the mechanisms involved — remains a difficult set of tasks.

It seems reasonable that many social network processes are volitional in the sense that actors have purposes, consistent with the first dictionary definition of process. Actors make choices over their use of time and, together with other actors, act in order to do something. Organizations forming “action sets” do so to act in concert. This leads to the formation of a network of organizations for some purpose. Continuing the inter-organizational example, organizational fields form. But this is seldom all of the story. The networks that form do so only partially by design. They are also shaped in unintended ways. An extant network facilitates some actions (and actors) and inhibits other actions (and actors). Put differently, the form of the network is relevant for its own evolution. In a specific empirical context there will be a sequence of network events which can be viewed as stemming from a network process.

At a minimum, studying network processes requires the use of time in addition to descriptions of network structures. Any cross-sectional description of a network at a single point of time does not describe a process. This would be statics rather than dynamics. It is possible that network data are collected overtime and then collapsed to form a single description. Kapferer (1969) does this, as did Roethlisberger and Dickson (1939). While it is possible to interpret these structural descriptions as an equilibrium state (for some — probably unknown — process), we do not include them within the domain of network processes. There has to be change (or not) through time which requires temporally ordered information rather than information summarized over a period of time.

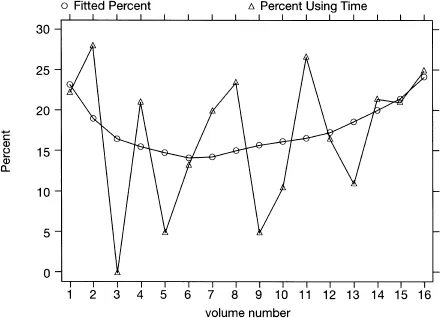

To help set the stage for our discussion, we examined the first sixteen volumes of Social Networks to see how often process in the “series of events” sense was featured in its pages. Of the 285 articles published between 1978 and 1994 we found 47 contained the use of time.3 Is this 16% incidence rate small? Before answering this largely rhetorical but difficult question, we need to say more about the coding of articles in terms of processual ideas. Any article with data at one point in time was coded as a non-process article. Some articles with processual words — like “dynamics”, “formation” and “disintegration” — in their titles were coded as non-processual if their data were cross-sectional. Consistent with the above argument, articles describing network structures at equilibrium were excluded also. Papers on biased network theory (even though the terminal state or distribution could only come as the result of a process operating with biases captured in parameters) were coded non-processual.4 Also, articles that used through time data but discarded the temporal information — for example Bonacich’s (1991) use of the Davis et al.(1941) Deep South data5 — were not included among the processual articles.

FIGURE 1.1. Percent of articles using time.

Rather than respond to the overall 16% in the rhetorical question, we look at the distibution through time of the use of time in articles found in Social Networks. This is shown in Figure 1. The high water marks, as it were, were in Volume 2 and Volume 11 when 28% and 27% respectively of the articles were processual. The graph also shows the lowess6 smoothed trajectory (Cleveland, 1979) which suggests the incidence of processual work is increasing currently — as do the raw data on the right. As we believe we are in an era when it will be fruitful to focus more on social network processes, this is a trend we like. Looking at the 16 volumes of Social Networks makes it clear that many of the cross-sectional articles are devoted to the development and discussion of procedures for describing structure. This is not a lament over the dearth of process and time in social networks research.7 If network processes are characterized as series of structures through time, there is a clear need to have sound structural tools. Indeed, using poor structural tools will threaten any effort to track structure through time, let alone provide the basis for attempts to “explain” structural phenomena. So while the Bonacich (1991) article is non-processual, it does lay out tools that will be very useful in studying networks through time.

It is tempting to treat “evolution of networks” and “network dynamics” as interchangeable terms. For us they have different meanings. We take network dynamics as the more general term and a generic statement of changes through time. The term evolution of networks has a stricter meaning that captures the idea of understanding change via some understood process. If we can lay out the “rules” governing the sequence of changes through time we have some understanding of a process that goes beyond simply observing change. Of course, a network system can be in equilibrium — consistent with the idea that some processes maintain structures. Paradoxically, the idea of a process may not be less relevant when there is no change through time. Without an understanding of a network process all we have is a single description. If we can locate that description in a through time framework, we can say something about the process(es) sustaining the (described) network.

2. PROCESS AS CHANGE IN SOCIAL STRUCTURES

There is a class of models, and corresponding network issues, that belongs here only partially. Articles that use processual ideas simply as illustrations and those advocating the use of processual mathematical ideas without specifying how this could be done are both put to one side. Undoubtably they will inspire future work but, for now, we will pay them no heed beyond the idea that change is important and that certain tools (say, difference equations or differential equations) may have great utility in modeling change.

We defined structure in terms of social actors and social relations and process as (generated) sequences of network events. To complete the picture of work in Social Networks, roughly 55% of the 47 processual articles are straightforward descriptions of networks t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- 1 The Dynamics and Evolution of Social Networks

- 2 The Weakness of Strong Ties: Collective Action Failure in a Highly Cohesive Group

- 3 The Emergence of Groups in the Evolution of Friendship Networks

- 4 Social Structure, Networks, and E-State Structuralism Models

- 5 Is Politics Power or Policy Oriented? A Comparative Analysis of Dynamic Access Models in Policy Networks

- 6 A Brief History of Balance Through Time

- 7 Evolution of Friendship and Best Friendship Choices

- 8 Longitudinal Behavior of Network Structure and Actor Attributes: Modeling Interdependence of Contagion and Selection

- 9 Stochastic Actor-Oriented Models for Network Change

- 10 Models for Network Evolution

- 11 Evolution of Social Networks: Processes and Principles

- Index