- 374 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

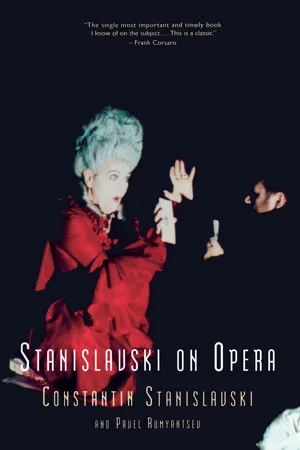

Stanislavski On Opera

About this book

Best known for his fundamental work on acting, Stanislavski was deeply drawn to the challenges of opera. His brilliant chapters here on Russian classics--BorisGudonov and The Queen of Spades among them--as well as LaBoheme will amaze and delight lovers of opera. Also includes 12 musical examples.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

In the Opera Studio

IN JANUARY 1921 Stanislavski was offered an old private house, 6 Leontyevski Pereulok, which had escaped the conflagration when Moscow was burned in 1812. The facade is not distinguished in any special way, but from the courtyard behind it one discovers all the peculiarities of a nobleman’s home dating back to the days of Griboyedov. There is a large two-storied addition which encloses an oaken staircase leading to the second floor. It is so old that the lower-floor entrance to the house is now below today’s ground level. There are also little balconies which have been added, presumably in the first half of the 19th century.

This building was not only the last residence of the great theatre director but was also his working laboratory. About one quarter of the second floor is occupied by a large hall with columns (the former ballroom). It was here and in the room adjacent to it that the Opera Studio of the Bolshoi Theatre, which Stanislavski had agreed to direct, “settled”. Lessons and rehearsals went on without interruption here from early morning to late evening. The piano was never silent except at night. In order to carry out his plan of incorporating his system of acting into opera, Stanislavski immersed himself completely in the world of music and singing.

All he had to do to go to rehearsals, which were carried out on strict schedule, was leave his study, cross a low-ceilinged vestibule with four columns, scarcely higher than Stanislavski himself, and enter the hall where rehearsals were in progress all day long. Every free moment he had Stanislavski would use to come over to see how the work was going on.

“Am I interrupting?” he usually said as he glanced cautiously into the large room. “Please go right on!”

But of course within five minutes he had taken over the rehearsal himself and was working away with the singers. This was extra instruction he gave the young players in addition to their regular training in his system of acting.

“First we must find a common language,” Stanislavski would say, “then we shall try to combine the art of living a role with its musical form and the technique of singing. After that we shall try out the validity of our work in performances. But to reach the point of actual performance we must go through a lot of preparatory improvisations. These will be based on songs and individual scenes from operas.”

This coherent program of work was necessary to the development of Stanislavski’s method of training which was not yet generally accepted in our theatres—that came much later.

The proponents of “pure operatic singing”, those devoted to the old routines, did not accept Stanislavski’s ideas about opera and they did their best to prove that if a singer has a real voice he does not need any training in acting.

The makeup of this Opera Studio group also made Stanislavski realize that he would be obliged to begin his training with the simplest exercises and sketches. The group, aside from a very few singers from the Bolshoi (K. Antarova, V. Sadovnikov, A. Sadomov), was made up of youngsters from the Moscow Conservatory of Music.

In order to keep to the historical truth of the record it must be said that certain other well-known singers were in the Studio, but not for long. In connection with this fact Stanislavski said:

“You must remember that a strong group is formed not by outstanding singers, these will always be lured away from us by other opera managements with promises of big salaries. The core of our Studio will consist of good singers of what we may call average talent, but who love their work; cultivated singers and actors who are welded together into an ensemble, who cannot be thrown off balance by the temptation of becoming stars, or acquiring great personal fame.

‘First we shall go through a course of preparation for opera which was not included in your conservatory training. Until you have finished that you will not be fit to set foot on our operatic stage, that is to say until you have chosen as the goal of your artistic life a kind of singing which is not only beautiful but also informed with that thought and inspiration. That kind of singing is without exception the true kind for all of you.’

The theory of the Stanislavski acting “system”, daily exercises to music, sketches acted out for the purpose of giving a basis to the most varied kinds of body positions, movements in space, the freeing of muscular tenseness and finally, the principal and most interesting work, the singing of arias and lyrical ballads (in the execution of which the students synthesized all the component parts of the “system”)—all this preparatory work was done by the students before they began to put on any Studio productions.

Stanislavski in teaching others was at the same time learning himself. He listened with closest attention, for example, to the lessons on orthophonics and singing diction given by N.M. Safonov, who had the gift of brilliant exposition in analyzing words and the way to achieve expressiveness through them. He knew how to get a singer to feel very deeply the meaning of a lyrical ballad and how to use a variety of techniques, including diction and vocal training, to bring that meaning fully to life—in this he was supreme. Of course, one could always learn from such a great teacher as Safonov and we young singers listened to him avidly during our lessons and “sweated it out” with him at the piano, repeating dozens of times a phrase that did not come off right. Unfortunately he died in 1922.

Concomitantly with our practical work on the “system” Stanislavski gave us a course of lectures drawn from what was later to become An Actor Prepares and Building a Character. At that time Stanislavski was in the process of formulating those books.

Our studies lasted a long time, nearly five years (1921–1926), and continued side by side with the readying of productions. They were carried on by Stanislavski and his assistants. Later on, especially by the new young members, the Studio was called the “School on the Move.”

In the early part of the existence of the Opera Studio Stanislavski was greatly assisted by his sister Zindaïda Sokolova and his brother Vladimir Alexeyev, who undertook all the preparatory training of the young singers.

Vladimir Alexeyev was a good musician. He had a refined sense of the rhythmic side of the acting of opera which occupies such an important place among all the other components of a performer in opera.

Stanislavski himself placed the greatest significance on rhythm: “No, you have not yet established the rhythm of this part of your role. You have not got it under control, you do not savour it. Ask the advice of my brother,” he used to say.

Zinaïda Sokolova helped the students to create the inner score of a part; she had the gift of finding the subtlest shadings for that inner life. The whole pattern of “Tatiana’s Letter” scene was worked out by her with N.G. Lezina; it was on the whole approved by Stanislavski and included in the production of Eugene Onegin..

The man who taught the Stanislavski “system” of acting was N.V. Demidov. He was well informed concerning the psychological foundations of Stanislavski’s work and even helped him in the preparation of material for his books, a fact which the author registered with gratitude.

One half of each day was devoted to class activities and the other to the preparation of performances.

The first three scenes of Eugene Onegin:“The Arrival of the Guests at the Larins’,” “Tatiana’s Letter,” and “The Meeting,”were the basis for Stanislavski’s practical work on the production.

Here he put two main objectives before the young actor-singers. The first was to achieve expressive, incisive diction, thanks to which they could convey clearly and colourfully the words they sang. “Fifty percent of our success depends on diction. Not a single word must fail to reach the audience.” That was the “leitmotiv” of Stanislavski’s work with singers.

The second objective was the complete freeing of their bodies from all involuntary tensions and pressures, for the purpose of achieving easy, simple handling of themselves onstage. It was to achieve this ability to free their bodies from excessive tenseness, especially in the arms, wrists and fingers, that daily exercises were devoted. They were all done to music in order to train the singers in making every movement consonant with musical rhythms.

In the process of projecting his voice a singer is obliged to tense certain muscles (of the diaphragm, the intercostal muscles, the larynx); that is to say these are working contractions which are necessary to the actual singing. It was the principal aim of a whole series of exercises prescribed by Stanislavski to make a distinction between the working contractions and superfluous tensions, thus leaving all the other muscles completely free. He was always on the watch for those unnecessary tensions in the body, the face, the arms, the legs of a singer while performing. When an artist is performing in accordance with his inner feelings he must not be impeded in his movements by muscular contractions. The singer’s whole attention must be centered on his action.

“Actors onstage are often fearful that the public will be bored if there is not enough gesturing, and therefore they go through a whole lot of motions,” Stanislavski used to say. “But the end result is random and trashy. On a large stage, especially, restraint is above all necessary and this can only be achieved if one has complete control over all of one’s muscles.”

“Thoughts are embodied in acts,” Stanislavski taught us, “and a man’s actions in turn affect his mind. His mind affects his body and again his body, or its condition, has its reflex action on his mind and produces this or that condition. You must learn how to rest your body, free your muscles and, at the same time, your psyche.”

Exercises for the purpose of relaxing muscles from ordinary tensions in order to acquire plasticity of movement—easy walking, the ability to govern the use of one’s arms and hands—were set down by Stanislavski as musts for a singer-actor of his school.

These exercises were conducted in a certain order: The students stood in a semicircle and, while music was played, went through various forms of gymnastics. Stanislavski told the musician in charge, one Zhukov:

“What we need is eight quarter notes for the raising of the arms, elbows, hands and fingers; also eight quarter notes for their relaxation and return to position. We want your help in harnessing the energy and then in releasing and relaxing it.

“First relax the muscles of the hands so that they are completely free and hang from the wrists as inertly as strings. Swing them backwards and forwards, separately and together,” he said. “After that the fingers must be so relaxed that they dangle from their joints. Then raise your arm to your shoulder, free that from all tension, and then let your elbow dangle from its joint. Shake the lower part of your forearm from your elbow down lightly and freely.”

To free the muscles of the legs it is necessary to stand on one leg, relax the foot of the raised leg, make it inert, watching mentally the lack of feeling in the toes. Then make rotary movements with the free foot. Stanislavski himself was so accustomed to these exercises that while he was seated, for instance at a rehearsal, he would twist his free foot and test its flexibility. These exercises enabled him to have a light, mobile way of walking, for which he was famous up to the time he was very old. He was fond of repeating that “a flexible foot and toes are the basis of lightness of walking.”

While holding one’s leg off the ground, relax the tension of the whole shank and gently rotate the knee joint. Then raise the leg, bend the knee, relax the whole, and slowly let the leg down.

In relaxing muscular tensions in the neck, one throws one’s head forward and then by movement of the body causes it to roll from side to side. Then, seated on a chair and having relaxed the neck muscles, one throws one’s head backwards and lets it roll around at will. While executing this exercise one imagines oneself in a state of sleep.

To relax the muscles of the shoulders and chest, the torso should be slightly inclined forward, with arms hanging inertly, and the waist muscles quite free.

After these exercises one could gradually relax all the muscles of the body and drop to the ground like a sheaf of wheat.

“These exercises," said Stanislavski, “develop a sense of tranquility, of self-control and power, as well as the clear understanding of one’s muscular structure.”

There were, of course, some singers who deep down in their vocal being considered that the exercises of the relaxing of muscular tensions were quite superfluous, that they bore no relation to singing. “for singing mannequins such exercises are indeed superfluous,” said Stanislavski, “but for living human beings, if they wish to remain such on the stage, they are imperative.”

One must note that it was impossible to imagine all of Stanislavski’s exercises as fun, as fascinating things to do for the participants. At times there was stubborn, monotonous repetition, grinding work done for the sake of art. Yet even to this dull monotony Stanislavski maintained an attitude of enthusiasm and enjoyment as great as when he was carrying on a rehearsal. And he exacted the same kind of joy in work from everyone else.

Daily training in how to walk with graceful fluidity was obligatory before the beginning of any rehearsal; the exercises were necessary as a means of softening and warming up the body, the physical apparatus of an actor. “The singer-actor needs them fully as much as he does his daily vocalization exercises,” Stanislavski would say.

The exercises in smooth walking were begun to very slow music. In the course of two measures in very slow time (adagio) only one step was made so that the weight of the body imperceptibly and smoothly passed from one leg to the other without the slightest hitch. The sole of the student’s foot and the movement of the toes played a great part in this beginning exercise.

“Your feet must be very soft springs in order to carry the weight of your body smoothly. Remember the example of a horse, of the highly trained Orlov breed of trotter—you can put a glass of water on his back and it will never spill. Try to achieve tha...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- ABOUT THE CO-AUTHOR

- TRANSLATOR'S FOREWORD

- 1.In the Opera Studio

- 2. Eugene Onegin

- 3. The Tsar's Bride

- 4. La Bohème

- 5. A May Night

- 6. Boris Godunov

- 7. The Queen of Spades

- 8. The Golden Cockerel

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Stanislavski On Opera by Constantin Stanislavski,Pavel Rumyantsev in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Performing Arts. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.