- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Published in 1990, Poor Reception is a valuable contribution to the field of Communication Studies.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Poor Reception by Barrie Gunter in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Communication Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

| 1 | The Growth of Television News |

THE GROWTH OF NEWS ON TELEVISION

Television news is the most pervasive source of public affairs information in western industrialized societies today. The provision of news has come to be regarded by broadcasters and audiences alike as one of the most important functions carried out by television, a fact that is illustrated by the amount of air time routinely occupied by news programmes in the schedules of major networks and local TV stations, and by the behaviour of many millions of people who have their sets tuned in to television news bulletins every day.

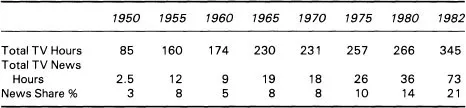

The news has been an important part of the development of network television from the very beginning. Today, news programmes constitute a large segment of total programme output for major television networks. In the United States, for example, network television news programming expanded from 2.5 hours a week in 1950 to over 70 hours a week by the early 1980s, or from about 3% to 21% of regularly scheduled programming (Nielsen, 1984) (see Table 1.1). In 1950, U.S. television audiences had a choice of just two 15-minute programmes transmitted at one time, whereas nowadays they have 28 network programmes to choose from, spread across all times of the day.

Regularly scheduled news programming on U.S. network television increased in amount substantially during the first half of the 1950s. During the early days of television news, the style of presentation changed too. By the middle of the decade, news “personalities” began to emerge, adding a more friendly and human touch to the news. The news continued to be broadcast in 15-minute prime-time segments throughout the 1950s but by 1955 had already begun to establish itself in its now traditional early evening time slot. By this time also, NBC’s Today Show had expanded regular news coverage into weekday mornings.

TABLE 1.1

The Growth of Network News in the US

The Growth of Network News in the US

Source: Nielsen Television Index Ratings reports, 1984. Reprinted by permission of A.C. Nielsen, Inc.

Note: Excludes specials and programmes under 5 minutes duration.

Between 1955 and 1960, the networks continued the development of their main early evening news broadcasts. Weekend reporting in 30-minute bulletins was introduced in a move which set the stage for extended news formats on weekdays. During the 1960s news personalities became firmly established and were an important ingredient of a show’s success with the audience. The main evening news shows were expanded to 30 minutes, and direct or “head-to-head” competition between simultaneously presented programmes became a feature of the schedules.

During weekdays, there was an increase in the number of 5-minute news briefs and updates, and weekend news became a familiar part of the network schedules. In 1967, CBS introduced its Morning News programme to provide a competitor for NBC’s Today Show. With this continued expansion of network news, news “anchors” came to be supplemented more and more by correspondents and reporters who contributed on special news topics.

The 1970s saw further developments in network news. By 1975, early evening news was broadcast on all networks at 6:30 to 7:00pm, and this format (with different “anchors”) was also used on Saturday and Sunday. Early morning news became available on all networks during the same year, with the introduction of Good Morning America by ABC. Short-duration news shows designed especially for children also appeared.

Although by 1980 all main news programmes were of 30 minutes duration or longer, the next couple of years witnessed an unprecedented rate of growth of news on television with the expansion of news into previously unscheduled late night or very early morning time periods. During the first 2 years of the decade, network news coverage in the U.S. doubled (see Table 1.1). News growth during this period, however, has not been restricted to the networks. With cable television, subscribers across America gained access to continuous 24-hours-a-day, 7-days-a-week news and weather information services.

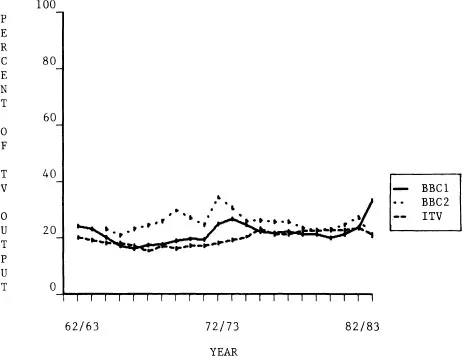

FIG. 1.1 TV network news output in the UK. Percentage of Total Output on Each Channel Devoted to News and Current Affairs Programmes

In the United Kingdom, television began as a regular high-definition service on 2 November 1936. At that time it showed Gaumont-British and British Movitone newsreels such as those shown in the cinema. There were only 2 hours of television a day then, one in the afternoon and one in the evening, and only 400 sets in the London area could receive the service. Television closed down on 1 September 1939 for the duration of the war. It returned on 7 June 1946 and spread slowly across the country. But until 1954, there were no television news programmes, other than outside broadcasts of major events and newsreels.

In 1948, the British Broadcasting Corporation progressed to making its own newsreels, which, from weekly editions with repeats, became biweekly and eventually nightly. In those days, radio was the principal medium people turned to for the most up-to-date news. No efforts were made to speed up the news process on television.

The situation began to change in 1953 when, following the Coronation coverage, the demand for television sets grew. In 1954, with the promise of a new Independent Television channel providing competition, the BBC introduced Television News and Newsreel, heralded as “a service of the greatest significance in the progress of television in the UK” (Davis, 1976, pp. 12–13). In fact, all it consisted of each night was a 10-minute broadcast with a reading of the latest radio news to an accompaniment of still pictures, followed by the familiar newsreel.

With Television News and Newsreel however, came the television newsreader. The first newsreaders were radio men and did not appear on the screen. Newsreel film footage in those days was silent and accompanied by appropriate mood music. There was no attempt at this early stage to create a new form of news presentation—television news was little more than illustrated radio. The BBC had no intention of employing any new techniques which might be construed as sensationalising or personalising the news. The Corporation’s declared policy was: “The object is to state the news of the day accurately, fairly, soberly and impersonally. It is no part of the aim to induce either optimism or pessimism or to attract listeners by colourful and sensational reports. The legitimate urge to be ‘first with the news’ must invariably be subjugated to the prior claims of accuracy” (BBC, 1976b).

Following the introduction of a second major television network, Independent Television News (ITN) began on September 22, 1955. According to ITN, the emphasis of television news should be visual and should interest the greatest number of people. The style ITN adopted was in contrast to the BBC’s illustrated radio format and was inspired to some extent by American television news broadcasting. Rather than simply using newsreaders, ITN opted for newscasters, who were trained journalists who provided their own input into the writing and compilation of the news programme. These individuals were chosen not simply for their professional experience in journalism, however, but also for their personalities. The policy adopted at ITN was to make the news more human and friendly than it had hitherto been. In the beginning, ITN broadcast three news programmes each weekday, at noon, 7:00 pm, and 10:00 pm, and two daily on weekends. The new newscasters were seen by viewers not only presenting the news and introducing stories on film but also interviewing and reporting their own stories. For the first time on British television reporters put direct and pointed questions to politicians and persisted until they answered. Film crews and reporters also went out and sought and recorded the views of the men and women in the street—”vox pop,” as they became known in the profession. Often these early film reports featuring interviews with the ordinary working folk involved in social or industrial disputes had tremendous impact.

With the birth of ITN, for the first time the news also contained elements of humour, usually delivered by the newscaster as the final item in the programme. Davis (1976) quotes one early amusing example: “In Israel a car taking an expectant mother to a maternity hospital collided with a stork. An hour later the mother gave birth to a healthy boy. The stork was stunned and slightly injured. Latest reports say that it is doing as well as can be expected” (p. 18).

Following ITN’s lead, the BBC introduced a 15-minute illustrated news bulletin in which newsreaders were shown on camera, though at first anonymously and only during the headlines. During the late 1950s, the BBC’s news became more human and more personable as its newscasters too were finally named and took on a friendlier style.

For historians of television news in Britain, the next major turning point is identified with the Cuban missile crisis of 1962, when the United States secured evidence of the establishment of Russian rocket bases on Cuba, 90 miles away from the Southeast coast of the United States. President John F. Kennedy appeared on U.S. television and warned that any nuclear attack launched from Cuba against any nation in the western hemisphere would be met with a full retaliatory response against the Soviet Union. As U.S. forces were put on full alert and the world waited for a week on the brink of nuclear war, it was only broadcast news via radio and television, and not newspapers, that was immediate enough to provide news of the latest developments. With two television channels by now serving the British nation as a whole, it was television that the public turned to. At the same time, television became, for the first time in Britain, the chief mass media source for news.

During the second half of the 1960s, television news in the United Kingdom expanded further with the introduction on both major channels (BBC1 and ITV) of main half-hour news programmes on weekdays. Once again, America had shown the way, with CBS’s Evening News with Walter Cronkite, which began in September 1963, followed by NBC’s Huntley-Brinkley Report. Although BBC2, the third channel, included a half-hour news programme when it began in April 1964, the audience for this transmission was very small. Half-hour news first came to a major channel in the United Kingdom on 3 July 1967, when ITN introduced News at Ten. This move was regarded as one not simply of lengthening the news but of providing room for greater flexibility. Until then, the news had been delivered in short bulletins, whereas in-depth coverage had been confined to current affairs programmes. This new extended news programme was aired at 10:00 pm. The independent companies were reluctant to transmit it any earlier because they believed it would be unacceptable to the mass audience interested primaril...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- PREFACE

- Acknowledgments

- 1 THE GROWTH OF TELEVISION NEWS

- 2 THE RECEPTION OF TELEVISION NEWS

- 3 LOCATING THE SOURCES OF BAD RECEPTION: A COGNITIVE RESEARCH PERSPECTIVE

- 4 NEWS AWARENESS AND RETENTION ACROSS THE AUDIENCE

- 5 ATTENTION TO THE NEWS

- 6 STORY ATTRIBUTES AND MEMORY FOR NEWS

- 7 TELLING THE STORY EFFECTIVELY

- 8 PACKAGING THE PROGRAMME

- 9 PICTURING THE NEWS

- 10 HEADLINES, PACE, AND RECAPS

- 11 SCHEDULING THE NEWS

- 12 IMPROVING UNDERSTANDING

- REFERENCES

- INDEX