- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Atmospheric Processes and Systems

About this book

Atmospheric Processes and Systems presents a concise introduction to the atmosphere and the fundamentals of weather. Examining different aspects of the mass, energy and circulation systems in the atmosphere, this text provides detailed accounts of specific phenomena, including

* the composition and structure of the atmosphere

* energy transfers

* the cycle of atmospheric water in terms of evaporation, condensation and precipitation

* pressure and winds at the primary or global scale

* secondary air masses and fronts

* thermal differences and weather disturbances.

The text includes sixteen boxed case studies, annotated further reading lists and a glossary of key terms.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I Introduction to the Atmosphere

Since this book is concerned with physical processes and interactive systems within the global atmosphere, it is logical to consider first the composition and structure of the atmospheric environment. The word atmosphere is derived from the classical Greek words atmos (meaning vapour) and sphaira (meaning sphere). However, it is now used less restrictively to denote the gaseous sphere that surrounds Planet Earth and includes water vapour, numerous gases and aerosols.

1 The composition of the atmosphere

Atmospheric constituents have a significant role to play in the functioning of weather systems and short-term climate change. This chapter covers:

- the average composition of a dry atmosphere

- the contribution of variable gases to total atmospheric composition

- the contributions of carbon dioxide and ozone

- the roles of water vapour and particulate matter

- case study: the acid rain problem

Air (the material of which the atmosphere is composed) is a mechanical mixture of a number of different gases, each of which acts independently of the others. In determining the relative proportions of these ‘constant’ constituents, it is convenient to consider them first in terms of dry air, which is free from any variable components both in space and time (particularly water vapour and carbon dioxide). A typical analysis gives the percentages listed in Table 1.1. These three gases make up 99.96 per cent of dry air, and the remaining four-hundredths of one per cent consist of minute quantities of various inert gases (namely neon, helium, krypton and xenon), hydrogen (H2), ozone (O3), carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), halogen derivatives of organochlorine compounds such as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), nitrous oxide (N2O) and aerosols. With the exception of O3, CO2, CH4, CFCs and aerosols, the components are all ‘fixed’ gases that do not vary in their relative amounts up to a height of 80 km. Consequently, near the surface, there is a balance between the production and destruction of these gases, especially nitrogen and oxygen.

For example, nitrogen is removed from the atmosphere primarily by biological processes (mainly involving soil bacteria) and is replaced by decaying plant and animal matter. Oxygen is removed from the atmosphere when organic matter decomposes and when oxidation takes place with a wide range of substances. Its removal is also associated with respiration, when the lungs take in oxygen and release carbon dioxide. Conversely, oxygen is added to the atmosphere during photosynthesis by plants when solar radiation is used to combine carbon dioxide and water to produce sugar and oxygen. In terms of the functioning of atmospheric processes and systems interactions, these fixed gases have little significance. Far more important are the variable and minute (‘trace’) gases (such as carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide, and methane) and aerosols, CFCs, ozone and (of course) water vapour. Table 1.2 illustrates the percentage composition of these variable gases, and their minuscule contribution to the total concentration masks the fact that these gases are responsible for large-scale global warming/cooling events (see Case Study 3). Furthermore, the important role of CFCs in ozone depletion (see Case Study 2) cannot be appreciated from Table 1.2, where their 0.0001 ppm concentration is the smallest of all the constituents represented.

Table 1.1 Average composition of the dry atmosphere (below 80 km)

Table 1.2 Contribution of variable gases to the total atmospheric composition

It is apparent that variable trace gases have a significant role to play in the functioning of weather systems and short-term climate change. The contribution of carbon dioxide to the so-called greenhouse effect and global warming has received considerable media attention in recent years, and the contributions of methane, nitrous oxide and CFCs are also significant (see Case Study 3). The so-called ozone ‘hole’ over Antarctica (see Case Study 2) has been public knowledge since 1984, and the banning of CFCs resulted from universal concern about increasing skin cancer. Carbon dioxide and ozone are clearly the most important variable gases in the atmospheric environment and their supply/removal from the atmosphere demands special consideration.

Carbon dioxide is a product of combustion, soil processes, oceanic evaporation and various organic processes (e.g. respiration) and is continuously consumed by plants through photosynthesis. Although these processes are not always balanced, the oceans try to regulate the supply of carbon dioxide by dissolving considerable amounts. Even so, carbon dioxide variations are evident over time associated with the ‘locking-up’ of large quantities of carbon in the form of coal and oil (e.g. 1014 tons of CO2 were withdrawn from the atmosphere during upper Carboniferous coal deposition 300 million years ago). Conversely, this carbon can be liberated (and released into the atmosphere) by the burning of fossil fuels. For example, it has been revealed that the CO2 content of the atmosphere has increased by 18 per cent since 1900 (from 296 ppm to 364 ppm in 1997).

It is now generally accepted that these significant changes in carbon dioxide concentrations have a dramatic role to play in the functioning of the greenhouse effect, through the absorption and re-radiation back to Earth of long-wave infrared terrestrial radiation. The exact mechanisms and consequences of this counter-radiation will be discussed in the Chapter 3 Case Study, and it will suffice to say here that CO2 depletion/accumulation are associated with global cooling/warming episodes. Carbon dioxide is essential for life on Planet Earth, for without the greenhouse effect, the Earth’s surface would be 30–40°C cooler and would resemble the surface of the lifeless Moon.

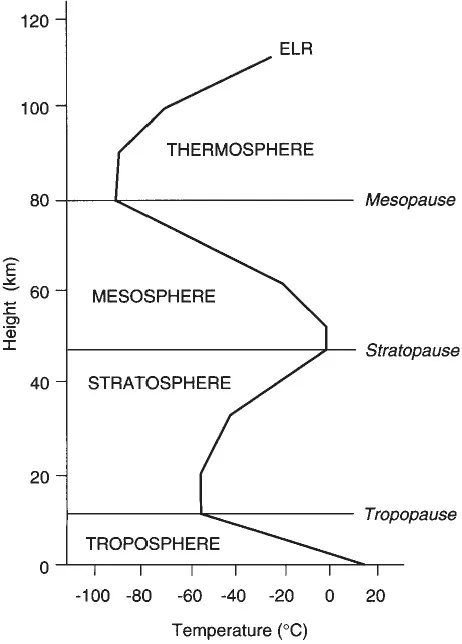

Figure 1.1 The structure of the atmosphere and the distribution of temperature (ELR).

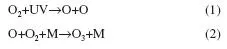

Ozone is concentrated in the stratosphere (Figure 1.1), especially at elevations between 16 km and 25 km, and is formed by the reaction of diatomic oxygen (O2) with ultraviolet (UV) solar radiation, with wavelengths below 190 nanometres (nm). This solar energy breaks the bond between the two atoms in the diatomic oxygen molecule, and some of the free oxygen atoms (O) collide and bind with a ‘normal’ oxygen molecule to form triatomic oxygen (O3) called ozone. This formation is speeded up by a neutral molecule (M), usually nitrogen, which acts as a catalyst for the reaction, and can be represented by the following equations:

Since molecule M also takes up the kinetic energy released in the above reaction, it accelerates and becomes hotter, so warming the stratosphere (Figure 1.1). This warming trend with increasing elevation is known as a temperature inversion, which is discussed in detail in the following chapter.

The build-up of ozone is further balanced by its natural destruction, since the gas reacts with ultraviolet solar radiation (at longer wavelengths than those required for its formation, between 230 nm and 290 nm), nitric oxide (NO) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2), as represented in the following equations:

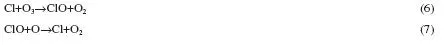

Most of the free oxygen atoms, illustrated in equation (3), combine with oxygen and neutral molecules to recreate more ozone, as in equation (2). This maintains the stratospheric chemistry in a state of equilibrium but it accentuates stratospheric warming with the absorption of more UV radiation in the recreation of ozone. Conversely, the chemical reactions in equations (4) and (5) permanently destroy ozone with its conversion into nitrogen compounds. Furthermore, injections of chlorine into the stratosphere from massive volcanic eruptions (such as El Chichón in Mexico in April 1982) can also deplete stratospheric ozone. Chlorine atoms (Cl) play exactly the same scavenging role as nitrogen compounds (in equations (4) and (5)), as is evident from the following equations:

The largest natural source of atmospheric chlorine is the production of methyl chloride from burning plant material in forest and grassland fires following lightning strikes. Even though only 10 per cent of this chlorine reaches the stratosphere, calculations made in the 1970s revealed that, at that time, methyl chloride may have been as effective at destroying ozone as were anthropogenically produced chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs). However, it is apparent that current ozone depletion over Antarctica, associated with abnormally high chlorine concentrations, is far too great to be caused by natural sources alone. It is now generally accepted that ozone equilibrium levels are being changed inadvertently by human activities, with a serious depletion in ozone concentrations and the creation of the infamous Antarctic ozone ‘hole’. CFCs, which degrade into chlorine, are held responsible for this creation, which will be discussed in the Chapter 2 Case Study.

So far in this chapter, we have emphasised the chemical composition of dry air, especially the contributions of the important variable gases CO2 and O3. However, it must be remembered that the atmosphere also contains a significant, if variable, amount of water vapour, with the variability mainly due to global temperature and associated moisture capacity differences between the poles and the equator. Part III will clearly demonstrate that the capacity of the air to ‘hold’ given amounts of water vapour depends on its temperature. In simple terms, the higher the temperature, the greater the amount of water vapour retained, although Chapter 7 will remind us of the more pertinent saturation vapour content complexities. Water vapour also varies spatially across the Earth’s surface associated with the distribution of land and sea masses and marked differences in the rates of evaporation/evapotranspiration (see Chapter 6) and precipitation (see Chapter 8).

A general, global average for the amount of water vapour in the atmosphere is 1 per cent moist air volume, but hot, humid equatorial air can contain as much as 4 per cent water vapour. Despite the fact that the molecular weight of water vapour is less than that of other gases in the air, 90 per cent of the vapour is concentrated within a few kilometres of the Earth’s surface. This is due to the increasing remoteness from the sources of atmospheric water (namely the world’s oceans, lakes and vegetation) with increasing elevation and the fact that air temperatures aloft are too low to maintain water in its gaseous state. Water vapour is vital in the atmosphere, since it initiates the hydrological cycle (see Chapter 6 and Figure 6.1),

maintains the water balance and has a significant role to play in the greenhouse effect (see Case Study 3).

maintains the water balance and has a significant role to play in the greenhouse effect (see Case Study 3).

Table 1.3 Aerosol production estimates (109 Kg yr-1)

In addition to the various gases mentioned above, the atmosphere contains a considerable amount of particulate matter or aerosols that are held in suspension, especially salt, dust and sulphates, from a wide range of primary and secondary, natural and anthropogenic sources (Table 1.3). Table 1.3 confirms the dominance of the natural supply sources, especially salt, dust and sulphates from hydrogen sulphide (H2S), which contribute up to 89 per cent of the total atmospheric aerosol production. Indeed, the only significant anthropogenic contribution is associat...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Series editors’ preface

- List of plates

- List of figures

- List of tables

- List of boxes

- List of case studies

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Part I Introduction to the Atmosphere

- Part II Radiative Fluxes and Energy Transfers in the Atmosphere and at the Earth's Surface

- Part III Atmospheric Water

- Part IV The Primary Atmospheric Circulation: Global Pressure and Winds at the Earth's Surface and within the Troposphere

- Part V Secondary and Tertiary Circulations: Synoptic Situations and Local Airflows

- Glossary

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Atmospheric Processes and Systems by Russell D. Thompson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Environmental Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.