1

INTRODUCTION

The Persians were one of the most highly developed civilisations of the ancient world. An Indo-European people, their influence on western European civilisations is apparent not only in regard to the linguistic affinity, but also in terms of culture, society, and even the Christian religion. The Persians were the first monarchy to create a world empire which included most territories of the known ancient world, from Egypt to India, and from southern Russia to the Indian Ocean. The fall of the first Persian empire (559–330 BC), which was ruled by the Achaemenid dynasty, was followed, after a hundredyear interlude of Hellenistic rule, by a new Persian power, the Parthians, who were based in northern Iran. In a gradual process of conquest, they recovered most of the former Achaemenid empire up to the River Euphrates. The Parthians ruled for almost 500 years (247 BC–AD 224), until they were succeeded by a new Persian dynasty, the Sasanians, which rose in Persis (modern Fars) under their king Ardashir I. Their empire fell following the Arab conquest of Mesopotamia and Iran in the mid-seventh century AD, and the subsequent coming of Islam.

The following remarks may serve to highlight the political and cultural achievements of the Persian empires. The most outstanding achievement of the Achaemenids undoubtedly was their ability to maintain control over an empire of such vast and unprecedented geographic proportions for 230 years. To a large extent this was due to the Persian kings’ acceptance of the political, cultural and religious diversity of the different peoples of the lands of the empire. No attempt was made to impose Persian language and religion on other people. Instead, the kings emphasised a policy which was, to use a modern phrase, all-inclusive. This does not mean to say that there were no repercussions in case of rebellious activities, but in principle the political and religious tolerance of the Achaemenid kings towards their subject peoples was adhered to, and was, by all accounts, overwhelmingly successful.

Being at the forefront of architectural and technological innovations meant that Persian kings prided themselves on employing the best architects and engineers at their courts. The creation of an extensive imperial road network in the Achaemenid empire not only established an unprecedented and unique infrastructure, but also led to the installation of the first known postal service in history. It provided a basis for the network of international routes, known collectively as the Silk Road, opened in the Parthian period, which linked Persia and the West with Central Asia and China. The architectural innovations of Persia include the vast columned halls of the royal palaces of Achaemenid Persia; the creation of round cities, an innovation of the Parthians and adapted by their successors, the Sasanians; the change from using columns to support a roof to the construction of barrel-vaulted structures called ivans, which characterise Parthian and Sasanian palace architecture; as well as the introduction of the squinch, an architectural feature which allowed the Sasanians to build a domed roof over a square space.

The Persian courts, especially those of the Parthians and Sasanians, took pride in an oral literary tradition which created the romances of Vis and Ramin and Khosrow and Shirin, stories which can be compared to, and may even have influenced, European literary tradition in stories such as Tristan and Isolde and Romeo and Juliet. Banqueting and hunting were recognised pastimes of the Persian kings and their courts, and found their way to the medieval courts of Europe. Chess and polo were amongst the games Khosrow I introduced to the Sasanian court from India, and Persian and foreign philosophers, astrologers and physicians were welcomed at the royal court to exchange knowledge and expertise.

Yet the high civilisation that was ancient Persia has been overshadowed by an overwhelmingly hostile press which is embedded in the European tradition, but which ultimately originates in antiquity. Europe’s first hostile encounters with the Persian world were the Persian Wars of 490 and 480/79 BC. These wars became an event of world-historical importance, shaping European historical tradition and Europe’s view of Persia, and indeed the Near (Middle) East. The Greek victories at Marathon (490 BC) and at Salamis and Plataea (480/79 BC) led to their transformation into mythical events, even gaining a religious dimension. These events triggered the creation of a Hellenic identity, in which the Greeks identified themselves in contrast to the ‘Barbarian’. Used initially as a reference to the Persians, it soon became a term for any non-Greek. The GreekBarbarian antithesis dominated Greek politics throughout the fifth and fourth centuries BC, and stood for an ideology in which Greek freedom was contrasted with Asian despotism and decadence. The Romans took up the baton from the Greeks, and as their political successors continued the propaganda of the western defence against the despotic East, be they Parthians or Sasanians. While the Greeks never distinguished between Medes and Persians, the Romans made no attempts to differentiate between Persians, Parthians and Sasanians. In their centuries-long wars against the empires of Parthia and Sasanian Persia, the Romans emphasised the weakness, effeminacy and the political and military decadence of ‘the Persians’, making little or no attempt to present a balanced view. It is the view of the Greek and Roman sources which has exerted considerable influence on the way we look at ancient Persia today.

So, who were the Persians? The Persians were an Iranian people who migrated from the east to the Iranian plateau in c.1000 BC. When they arrived in the region that is equivalent to modern-day Iran, they settled in different areas of the country alongside the indigenous population, the Elamites. Persians are attested in northwestern Iran, in the Zagros mountains and in Persis, modern Fars, in southwestern Iran. Another Iranian group were the Medes, who settled in the northwest of Iran, around the city of Ecbatana, modern Hamadan, and further north, in the area of Iranian Azerbaijan.

Elamite civilisation dates back to the third millennium BC. The Elamites were ruled by kings whose power was centred on two royal cities, Susa in Khuzestan, and Anshan in Persis. The Elamites were renowned as great warriors and appear in the Near Eastern sources as fervent enemies of the Assyrians. In the mid-seventh century BC the Assyrian king Assurbanipal defeated the Elamite army and sacked the city of Susa, which was destroyed and the surrounding land devastated to render it unsuitable for agriculture. Despite these events a new Elamite dynasty emerged, if only for a brief period of time, centred on Susa in the western part of the Elamite kingdom, while the area east of the Zagros mountains, including the city of Anshan, appears to have been deserted.

Elamite culture possessed a distinctive art and architecture, especially with regard to its religious architecture, exemplified in the ziggurat of Choga Zanbil, the temple constructed by the Elamite king Untash-Naprisha in the thirteenth century BC. Elamite rock reliefs attest to the importance of the celebration of religious rituals of the kings and queens of Elam.

No documents survive from Elam which would allow us to reconstruct the history of this kingdom, but building inscriptions and administrative documents attest to the fact that Elam possessed a long written tradition. Writing on clay, the Elamites used a cuneiform script which was distinct from Akkadian, though it did employ Sumerian logograms as word indicators. When the Persians settled in Elam, they adapted the Elamite script to conduct their administration. As far as can be deduced from the available evidence, the early Persian kings also adapted Elamite art and culture.

Median influence on Persia is less secure. In language and culture the Medes, an Iranian people, were related to the Persians. Yet the extent of their mutual affinity, or of Median influence on Persia, cannot be determined with any certainty. The Greek historian Herodotus, who described the political dependency of the early Persians on, and their cultural debt to, the seemingly superior Medes, presented Media as a kingdom which had been unified under Deiokes and reached its political zenith under Cyaxares and his son Astyages. But in recent studies scholars have placed serious doubt on the existence of a united Median empire.1 From the eighth century BC onwards, Assyrian documents mention the Medes alongside several other peoples who live in the northern Zagros mountains, and frequently refer to the numerous kings who rule over them. Median sites such as Nush-e Jan, Godin Tepe and Baba Jan, which represented local centres of power, support the idea that Media was most likely a confederation of smaller states. During Assyrian expansion northward some Medes were forced to accept Assyrian suzerainty, but at the end of the seventh century the Median king Cyaxares fought a victorious battle against the Assyrians. This achievement may have led to the brief political sovereignty of Cyaxares and his son Astyages over other Median peoples, centring their power in the city of Ecbatana.

Geographically, the core region of imperial Persia is roughly equivalent to modern Iran. The Iranian plateau is situated between the Arab world in the west, India in the east and Turkoman Central Asia in the north. The plateau’s altitude ranges between 1,000 and 1,500 metres. The country is dominated by the mountain ranges of the Alburz in the northwest, which has the highest mountain in Iran, the Damavand (5,610 m), the Kopet Daǧ in the northeast and the mountains of Khorasan. The Zagros mountains stretch in a north–south direction in the western part of the country, while the eastern territory is marked by two deserts, the Dasht-e Kavir and the Dasht-e Lut. The plains are ideal for pastoral agriculture, while the lands of Khuzestan and of the region along the Caspian Sea are suitable for arable agriculture. The climate of Iran changes dramatically across its north–south extent, with cold, harsh conditions in the north and excessive heat in the south. It was the southwestern province of Persis which witnessed the birth of the first Persian empire under its king Cyrus II.

2

THE ACHAEMENIDS

HISTORICAL SURVEY

The early Persian kings

In the second half of the seventh century BC a Persian, named Cyrus I (Elam. Kurush; c.620–c.590), inherited the title of ‘King of Anshan’ from his father Teispes. They ruled over a principality located in southwest Iran, called Parsa, or Persis (modern Fars). This region had formerly been part of the kingdom of Elam, which had stretched across the Zagros mountains from Khuzestan to Persis, and was controlled by two respective capitals, Susa and Anshan. But the defeat of the Elamites by the Assyrian king Assurbanipal and the destruction of the western capital Susa in 646 BC had created a power vacuum in Persis. The Persians, who had lived peacefully alongside the indigenous Elamite population for several centuries, had established themselves sufficiently to create a noble class, out of which Teispes emerged as the principal leader who filled the political vacuum. In recognition of the former Elamite power Teispes and his immediate successors adapted the Elamite royal title, ‘King of Susa and Anshan’, to the title ‘King of Anshan’. This was an act of political symbolism with which the Persians gave weight to their role as successors of the Elamite kings. In using this title they also acknowledged the eastern Elamite capital, Anshan, which had ceased to function as a major city in the mid-seventh century BC.

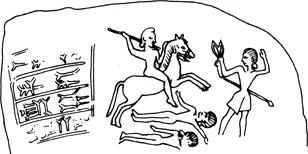

The inscription on his personal seal refers to Cyrus I simply as ‘Cyrus of Anshan, son of Teispes’, alongside an image which shows the king on horseback pursuing his enemies, some of whom are already lying slain on the ground (see Fig. 1). His affinity with Elamite culture was expressed in the adaptation of the artistic style of the Neo-Elamite period, as well as in the use of the Elamite cuneiform script for the inscription. His grandson, Cyrus II, expressed more confidence in his written testimonies, claiming the royal title for himself and his ancestors back to his great-grandfather Teispes.

It is possible that a certain Kurash of Parsumash mentioned in a Neo-Assyrian text of Assurbanipal (668–631/27?) is identical with Cyrus I. In recognition of Assurbanipal’s superiority over Elam after the fall of Susa in 646 BC, this Kurash sent a son, Arukku, with tribute to the Assyrian king. While the different rendering of the name Cyrus does not present a difficulty, the location of Parsumash is disputed and its identification with Persis uncertain. Yet there remains a possibility that the Assyrian record attests to Persian power in the eastern part of Elam.

Greek sources provide us with some information about Cyrus’ son and successor Cambyses I (c.590–559 BC). They tell us that Cambyses entered an alliance with the neighbouring kingdom of Media. The Medes had settled in northwest Iran, with Ecbatana emerging as a major centre of this region. Both the Babylonians and the Persians might well have regarded the Medes as a worthy ally against the dominant power in Mesopotamia, the Assyrians. The Median kings Phraortes (647–625) and Cyaxares (625–585) both launched attacks against Assyria and its capital Nineveh. Cambyses I may have sealed the political alliance with Cyaxares’ successor Astyages (585–550) with a dynastic marriage to his daughter Mandane. What is not certain is whether the alliance between the Median and the Persian king was one between equal partners, or one

in which the Persians were regarded as inferior to the Medes, as was claimed by the Greek historian Herodotus. In any case, it appears that the Persian dynasts were still at a very early stage of royal power. Their main aim was the defence of their kingdom, as no source records any expansionist activity during that period.

Figure 1 Seal of Cyrus I with Elamite inscription (drawing by Marion Cox)

The founder of the empire: Cyrus II the Great

This changed dramatically with the succession of Cambyses’ son Cyrus II (559–530), who is rightly regarded as the founder of the Persian empire. Within the space of about twenty years Cyrus II led a series of military campaigns in which he subjected the existing kingdoms of the known world, Media, Lydia and Babylonia, as well as territories east of Parsa, controlling an area roughly equivalent to the geographical territory of the modern Middle East, reaching from Turkey and the Levantine coast to the borders of India, and from the Russian steppes to the Indian Ocean. This was a phenomenal and outstanding achievement for a single ruler, whose charisma and military skill allowed him to command a vast, multi-ethnic army, and who enforced a political organisation of empire which remained an effective tool of imperial government for over 200 years.

Media was the first kingdom to succumb to Cyrus’ army in 550/49. Greek sources would have us believe that Cyrus attacked the Median king Astyages in a bid for political independence from Media. The familial element of this story, according to which this was a rebellion of Astyages’ grandson, added a particular poignancy. Whether this is a case of romantic fiction will remain a question of much debate, but the fact that not all Greek sources agree on this version should alert us to the possibility that the familial link could have been a fictional addition to the story of conquest in order to legitimate Cyrus’ rule in Media. Thus, in contrast, the fourthcentury BC Greek doctor and writer Ctesias explicitly states that no familial relationship existed between Cyrus and Astyages. This view corresponds to the Near Eastern sources which make no mention of a political or familial link between the ruling houses of Media and Persis. Furthermore, these sources claim that Astyages took the offensive in battle, leaving Cyrus to take a defensive position to his attack. According to the Babylonian Nabonidus Chronicle Astyages intended to conquer Persis and therefore mustered an army. But when part of his army deserted from the king and sided with Cyrus, the outcome of the battle was decided and Astyages’ fate was sealed. Cyrus immediately took control of the Median capital Ecbatana, confiscating the treasury and transferring its wealth to Persis.

[1] (Astyages) mustered (his army) and marched against Cyrus (Bab. Kurash), king of Anshan, for conquest [. . .]. [2] The army mutinied against Astyages (Bab. Ishtumegu) and he was taken prisoner. Th[ey handed him over?] to Cyrus [. . .]. [3] Cyrus marched to Ecbatana, the royal city. Silver, gold, goods, property, [. . .], [4] which he carried off as booty (from) Ecbatana, he took to Anshan. The goods (and) treasures of the army of [. . .]. (. . .)

(Nabonidus Chronicle col. II: 1–4)

Following Near Eastern tradition, Cyrus probably married a daughter of Astyages called Amytis (Ctesias FGrH 688 F1), thereby affirming his victory over the Medes.

Reasons why Astyages wanted to attack Persia in the first place remain obscure. It may have been due to his ambition to expand the Median realm, but he also could have recognised the growing power of Cyrus and was compelled to react before his power could pose a political threat.

Cyrus’ military triumph was marked by the foundation of the first Persian royal centre, Pasargadae (Elam. Batrakatash), in the plain of Marv Dasht in eastern Persis. The site was dominated by Cyrus’ palace and audience hall, as well as his tomb, placed on a six-stepped platform. In front of his residential palace Cyrus II built the first structured garden, a paradeisos (Elam. partetash), with irrigation channels dividing four rectangular spaces (see Fig. 2).

In a next step, Cyrus II conquered the regions north of Media, including Urartu, which was located around Lake Van, and the Lydian kingdom. Lydia was one of the most powerful and wealthiest kingdoms of the sixth century BC. King Croesus (c.560–c.547) had subjected the Ionian cities of the coastal area, and made them tributaries. An alliance with the Assyrian king, which extended the Neo-Assyrian system of overland routes from Mesopotamia to the Lydian capital Sardis, brought further prosperity. His fame in the Greek world was due to the fact that he was accredited as being one of the first rulers to mint coins. But militarily Croesus was in a weak position since he failed to secure military support from Greece and Egypt for his fight against Cyrus. Taking the offensive, Croesus crossed the River Halys and attacked the city of Pteria, traditionally identified with the ancient Hittite capital Hattusa, modern Boǧazköy.1 In reaction to this attack, Cyrus moved his army towards Cappadocia, confronting Croesus’ army, and forcing its retreat to Sardis after an indecisive batt...