eBook - ePub

The Enquiring Teacher

Supporting And Sustaining Teacher Research

- 280 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Enquiring Teacher

Supporting And Sustaining Teacher Research

About this book

First Published in 1988. Throughout this book 'enquiring teachers' is taken to mean those who are students on courses, successful completion of which depends in part on their undertaking one or more enquiries into their own practice or that of their colleagues. This Introduction presents some definitions and then discusses the implications for teachers who become students on enquiry-based courses, for the schools and colleges in which they teach and for the colleges, polytechnics, universities and teachers' centres which mount and teach the courses.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Enquiring Teacher by Susan Groundwater-Smith,Jennifer Nias,Jennifer Nias University of Cambridge; Susan Groundwater-Smith University of Sydney, Australia. in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

Why Enquiry-based Courses?

Enquiry-based courses in teacher education are founded upon well-reasoned and defended arguments. The section which follows articulates the rationale for the provision of enquiry-based courses. This rationale is predicated upon three different, but overlapping, assumptions underlying teacher research (in which teachers are learners, regarding and reflecting upon their own practice). These are: (a) that the focus of the enquiry should be of the learner’s choosing; (b) that having perceived the problem (should one exist) the learner should feel moved to change the conditions from which the problem arose; and (c) that the learner will see him/herself as a member of a community of enquirers, rather than as an isolated individual. Letiche, Bell and Rowland draw upon these assumptions in their presentations.

More specifically, Letiche challenges the notion of reducing enquiry, as part of an award-bearing course, to a technical exercise. He couples cognitive action with contextual action and emphasizes the social experience of collaborative learning. He analyzes the interaction between learning by doing, learning to learn and learning via group processes. The curriculum which he proposes for enquiry-based courses has been characterized by Letiche as a negative-curriculum, that is one which is defined by its non-values, by making clear what it is that students are not supposed to do. It is founded upon the notion that there is ‘no one privileged approach’ to enquiry but recognizes that certain forms and practices are inimicable to practitioner research. Letiche briefly illustrates his argument by drawing upon a medical education case study.

In the second chapter Bell brings our attention to the shift which enquiry-based courses require from the study of received knowledge to the active construction of practitioners’ epistemologies. This entails the ‘lived experience of an uncertainty about what is worth while’. Bell is critical of those protagonists of a particular form of teacher enquiry, i.e. action research, who reduce the research activity to an iconic cycle serving narrow, instrumental interests. He points to the problems in the current pressure for collaboration, for groups to undertake studies, which leaves unexamined the question as to whether group members have any common epistemology. Bell also draws our attention to the products of practitioner research; that is, what is it that the teacher-as-enquirer produces and to what use is it put?

Rowland, too, is concerned with epistemological questions. He examines critically the concept of personal knowledge and asks, ‘how does my body of knowledge relate to the knowledge of others?’ and ‘how does personal knowledge affect practice if it is merely unreflective introspection?’ By bringing together reading and personal experience Rowland indicates that a practitioner’s body of knowledge is constructed and nurtured in a number of ways.

These three chapters, then, lead us to formulate a rationale for enquiry-based courses as a practice which is itself dynamic and open to critique.

1 Interactive Experiential Learning in Enquiry Courses

There’s nothing so practical as a good epistemology.

Introduction

The enquiry-based curriculum for which I shall argue seeks to channel the participants’ energy.1 The students learn to look at their experiences through the eyes of curriculum goals which are non-instrumental in nature. It is as though they become external observers of their own experiences. This is neither a comfortable nor an easy experience. As long as enquiry courses are a pedagogical exception, one can expect that most enrolments will be by highly motivated students willing to take the risks involved in the management of their own learning. Thus, Antioch College’s internship curriculum was long able to draw on a willing student body who had consciously chosen an exceptional course of study. Antioch’s success led some educators to propagate internships as a solution to the work/university tension. But Dutch universities, with their required internships, prove that one cannot rely on this curricular innovation to solve much of anything. What worked well in a situation of self-selection does not achieve comparable results when it is required. Educationists often fall into the trap of generalizing their limited successes. Innovational success, based on a small staff and self-selected students, does not harbor general applicability. When we want students to get rid of the external vantage point (the world as seen by the curriculum) and to observe concretely a here and now, we have to make sure that our pedagogics do not freeze the situation. Learning goals quickly limit the categories of (self-) investigation. The organizational dynamics of the curriculum produce illustrations, models, guidelines and norms of grading. These define what the student has to do, a situation which is inimical to genuine enquiry. This argument is not leading to an equating of enquiry with anarchy. Disciplined professional and cognitive development can be demanded in enquiry course work. What we need is a framework of agreements clarifying what is not going to take place.2 These interdicts clarify the situation wherein one works. Agreements on what one is not going to do are in practice easier to justify, and more simple to arrive at, than are prescriptive rules. And more important still, they do not freeze the categories of thought. Given that individual social responsibility is enquiry learning’s most central point of departure, a negative code of research norms can at once act as a necessary procedural statement, and leave ample room for initiative. The mania to equip students with an efficient ‘tool kit’ leads educators to define behavioral goals, every-which-way. Enquiry becomes so many skills to be mastered according to a pre-set (ideally, highly efficient) research path. Enquiry then, has been operationalized. The intellectual and practical self-management crucial to experiential learning has been sacrificed to a technical approach. Genuine wrestling with a context has been replaced with pre-fab research techniques. Curricular clarity has been bought at the cost of rigidifying learning. ‘Proven’ teaching techniques, standard lessons, foolproof materials can all now be developed. But we cannot marshal real personal resources in this manner! Enquiry may need facilitation and/or support, but it cannot survive when moulded into a preset curriculum. If students are to attempt to solve practical problems as a learning exercise, they have to be left to get on with it. The educators have to adopt a low profile, as curriculum designers. The rule being developed here is:

DON’T INTERFERE TOO MUCH IN THE LEARNING PROCESS; DON’T BE AFRAID OF STUDENT INITIATIVE.

The corollary for curriculum development is:

DEFINE YOUR COURSE’S NON-VALUES; MAKE IT CLEAR WHAT THE STUDENTS AREN’T SUPPOSED TO DO.

I have, along with colleagues at the Rotterdam School of Management, developed enquiry course work, based upon a negative-curriculum, when facilitating student internships and while supervising student research projects.3 In both situations the stated goal was to encourage experiential learning. In this chapter I shall attempt both to clarify the role of experiential learning in enquiry courses and to examine how a negative-curriculum functions as a basis for enquiry learning. In conclusion, I will defend the thesis that interactive experiential learning defines an epistemology for enquiry course work which needs to be mastered if student work is to be both genuinely independent and subject to high standards of quality. It is important to note that I have limited my attention to issues and problems as they occur in degree granting courses. Since the form of enquiry course work which I know the best is student-based practitioner (action) research the results of this research will be used to illustrate my points. Specifically, I shall offer as both illustration and illumination an account of a graduate student’s research and practice wherein the student sought to both describe and prescribe his own actions.

The Nature of Experiential Learning

Experiential learning can be defined as not merely abstract: it is the ‘learning in which the learner is directly in touch with the realities being studied. Experiential learning typically involves not merely observing the phenomena being studied but also doing something with it such as testing the dynamics of the reality to learn more about it, or applying the theory learned to deliver some desired result.’4 Thus, when we discuss experiential learning we explore a form of interactive knowledge. Not abstraction or observation alone, but cognitive activity coupled to [appropriate] contextual action, is what takes place.

COGNITIVE ACTIVITY + CONTEXTUAL ACTION = EXPERIENTIAL LEARNING

Fundamentally, in the practice of experiential learning there is a place for the making of an argument, for the raising and testing of hypotheses, and for engaging in the other instruments of rational discourse. Experiential learning must not become an excuse for an educational process, wherein each person’s experience is a separate (positive) ‘truth,’ divorced from broader social and intellectual concerns, or where no prerequisite knowledge is demanded in the research process, which may lead to an impoverishment of research through neglect of methodology and of theory; or wherein there is no hierarchy, sequence, or continuity in learning. Experiential learning bases its ‘truth claim’ (at least in part) on the intuitive recognition of the givens presented. But this must not lead to the demand that learning be directly accessible or to a demand that expression not be complex. Detailed and concentrated study depends on the use of special research grammars and applied logics. These permit the student to make a buttressed interpretation. Learning not based on preparation which does not make use of investigatory skills, becomes irrelevant, discontinuous, fragmented, lacking in context, impersonal, ahistorical, and trivial. Experiential learning is not merely the passive, unprepared reception of sense data; it depends on active mental participation in ‘matters at hand’. It is not the purpose of experiential learning to increase impulsive reaction at the cost of thoughtful response; the manipulative stimulation of anti-intellectual ‘spontaneism’ is inimical to enquiry.

Experiential learning is based upon the study of contextually grounded givens. The interpretative labor of describing these ‘meaningfully’ is immensely active. By thinking through this activity, one encounters the hermeneutic process. I have tried to capture this line of development in a paradigm that is at once self-reflective (methodological knowledge) and socially dynamic (new ways of seeing/dealing with the ‘world’).

At least three different combinations of cognitive activity and contextual interaction have been proposed as sub-sets to experiential learning. Experiential learning is not identifiable with one prescribed technique; it is made up of a dynamic tension between the differing elements. The learning strategies of experiential learning do not stress either/or options, but the complementary utilization of a variety of approaches: learning by doing; learning how to learn; and learning through experiential group processes.

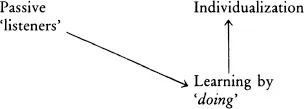

In considering learning by doing the emphasis is on a direct encounter with experience. ‘Progressive education,’ beginning in the twenties [the moving forward, step by step, to an improved use of individual powers, in order to be able to meet human needs], and ‘radical education,’ in the sixties [spiritual growth, through social exchange, directed towards individual ethical insight], both stressed learning by doing. The argument for learning by doing begins by denouncing the reduction in schools of learners into a passive mass of disinterested ‘listeners’; when motivated to learn, students will individualize themselves by doing things.

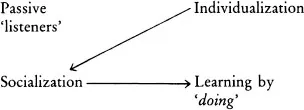

If we pursue the analysis of the rhetorical opposites used in the argument, we discover:

If we begin with the ‘individualizing’ effect that the stress on personal powers and needs has, we can rightfully criticize the evident lack of attention to the positive value (and cultural significance) of learning through social exchange. Everyday experience and material reality need to be acknowledged as a necessary background to all learning. The criticism of one-sided individualism, leads to an emphasis on socialization. This standpoint translates into a programme of learning by doing, wherein the learner is introduced to cooperative learning. Learning is not realized by the mere collecting of sense data; bare physical stimuli only become significant when mitigated by social experience. Modern knowledge is a result of human beings’ efforts to meet their social and physical needs. Knowledge must not be taught as so many empty symbols without meaning for the learner. Knowledge needs to become the learner’s ongoing reconstruction of reality based upon a dialogue between particular needs and shared aims.

Attention to the students’ readiness to learn, to motives and to constructive ingenuity is, in theory, all well and good; but how does one plan or evaluate course work grounded in the learner-context? How can one distinguish between genuine circumstantial commitment and the slavish following of imposed rules? Criteria for the ‘living through’ of situations are difficult to define. What is it to ‘have an experience’? What is the difference between mere sense perception, and experiencing? Does the instructor pre-structure the learning-field to stimulate experiential development? Should one provide so much order that meaning is inevitably to be found; or should there be a realistic threat of failure, wherein learning may not take place? What is the relationship between the ‘instructor’ [facilitator] and the ‘learner’? How can one evaluate learning-through-practice? How does one know that any learning actually took place? If the learner ‘experiences’, what right does the instructor have t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- PART 1. Why Enquiry-based Courses?

- PART 2. Pre-service Teacher Education: Some Dilemmas and Resolutions

- PART 3. In-service Teacher Education

- PART 4. Continuing to Change

- PART 5. Some Conclusions

- Note on Contributors

- Index