- 472 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Occupational Health Services

A Practical Approach

About this book

Workers and their families, employers, and society as a whole benefit when providers deliver the best quality of care to injured workers and when they know how to provide effective services for both prevention and fitness for duty and understand why, instead of just following regulations.

Designed for professionals who deliver, manage, and hold oversight responsibility for occupational health in an organization or in the community, Occupational Health Services guides the busy practitioner and clinic manager in setting up, running, and improving healthcare services for the prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and occupational management of work-related health issues. The text covers:

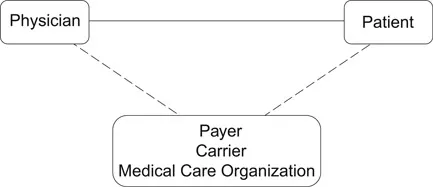

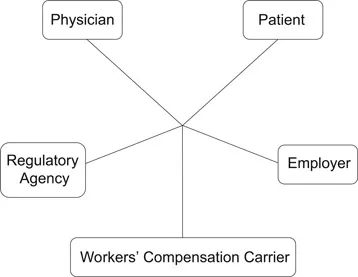

- an overview of occupational health care in the US and Canada: how it is organized, who pays for what, how it is regulated, and how workers' compensation works

- how occupational health services are managed in practice, whether within a company, as a global network, in a hospital or medical group practice, as a free-standing clinic, or following other models

- management of core services, including recordkeeping, marketing, service delivery options, staff recruitment and evaluation, and program evaluation

- depth and detail on specific services, including clinical service delivery for injured workers, periodic health surveillance, impairment assessment, fitness for duty, alcohol and drug testing, employee assistance, mental health, health promotion, emergency management, global health management, and medico-legal services.

This highly focused and relevant combined handbook and textbook is aimed at improving the provision of care and health protection for workers and will be of use to both managers and health practitioners from a range of backgrounds, including but not limited to medicine, nursing, health services administration, and physical therapy.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

1

The Occupational Health Care System

- Prompt and effective care for injuries and illness arising out of work.

- Documentation of the cause of the injury or illness and its relationship to work, for purposes of compensation and future prevention.

- Management of chronic conditions that are aggravated or affected by the work environment.

- Management to promote health, productivity, and well-being.

Occupational Health Care is a Separate System

- Health care for employees, insurance being the obvious expense and wellness and health promotion being a proactive strategy

- Health care for employees injured on the job (in some states employers have the right to specify which doctor sees the employee first)

- Preventing work-related injury and illness by identifying and controlling hazards in the workplace

- Preventing work-related injury and illness by monitoring the experience of workers over time

- Preplacement medical evaluation for new hires

- Accommodation for health problems and impairment (compliance with Americans with Disabilities Act)

- Communication with health care providers to ensure an early and safe return to work for injured employees, whether the injury was work-related or personal

- Evaluating workers’ compensation claims and tracking experience with work-related injuries and disease

- Certification of “serious” illness in an employee or dependent (under the Family and Medical Leave Act)

- Return to work and fitness for duty

- Certifying sickness absence

- Managing “presenteeism” (when an employee comes to work but is not functioning effectively due to health problems)

- Health promotion and wellness, for the employees’ benefit and to improve sustainable productivity

- Drug screening and how to manage it without disrupting the workplace and risking ethical, legal, and privacy problems

- Product safety and liability and the due diligence required of a producer

- Protecting the health of employees in company-run facilities, such as cafeterias and canteens

- Defending against “toxic tort” lawsuits and third-party legal actions

- Environmental hazards and managing the risk and liability beyond simple compliance with EPA regulations

- Compliance with federal and state regulations for occupational health (not all of which are OSHA).

Organization of Occupational Health Services

- Outsourcing. Corporate medical departments were closed and the services were contracted out to practitioners outside the employer’s organization. This trend had the paradoxical effect of increasing the total number of occupational health professionals and the proportion based in the community. However, the trend resulted in a reduction of influence within companies, less engagement in the employer’s specific needs, and loss of familiarity with the workplace. Some employers are now recruiting again because they have found that they need sufficient in-house capacity to manage contractors and to deal with internal matters.

- Delayering. Probably the most significant trend of all, delayering reduced or eliminated the upper- and middle-management layers of the company in order to streamline the organization, shorten the communications link, improve accountability, and increase efficiency. This trend was particularly important because these organizations lost the senior level of management that had been most familiar with occupational health services and its value proposition. Since outsourcing removed occupational health services from view and since the value of occupational health is rarely taught in business schools, new Master of Business Administration (MBA)-level managers almost never know how to manage occupational health services or how they contribute, unless they happen to have prior experience.

- Downsizing. Downsizing was the trend toward drastic reduction in the size of organizations, to the minimum required to conduct business. The objective was to boost profitability, force gains in productivity, and to streamline operations. Later, this was modified to “right-sizing,” reducing the workforce to the optimum required to do business. With a much smaller workforce, many employers saw no need to maintain in-house occupational health services.

- Devolution. Some employers substituted occupational health nurses for physicians or assigned reporting accountability for contract physicians to non-physicians, for functions that did not require a medical license. Many physicians were alarmed at the time and believed that nurses were taking their jobs, which led ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- List of Boxes

- List of Exhibits

- List of Contributors

- Preface

- 1 The Occupational Health Care System

- 2 Workers’ Compensation

- 3 Occupational Health Law

- 4 Occupational Safety and Health Regulation

- 5 Ethics

- 6 Corporate and In-House Occupational Health Services

- 7 Global Occupational Health

- 8 Strategic Planning

- 9 Hospitals and Medical Groups

- 10 Staffing and Personnel

- 11 Facilities and Equipment

- 12 Office Procedures

- 13 Records

- 14 Professional Preparation and Training

- 15 Marketing

- 16 Services and Service Lines

- 17 Quality and Performance Indicators

- 18 Benefit and Cost Analysis

- 19 Primary Care-Level Clinical Services

- 20 Periodic Health Surveillance and Monitoring

- 21 Hazard Evaluation and Management

- 22 Fitness for Duty

- 23 Equal Access

- 24 Absence and Leave

- 25 Independent Medical Evaluation

- 26 Impairment Assessment

- 27 Drug and Alcohol Testing

- 28 Employee Assistance Programs

- 29 Psychological Health and Safety

- 30 Health Promotion

- 31 Emergency Management at the Enterprise Level

- 32 Medicolegal Services

- Appendix 1: An Occupational Health Audit

- Appendix 2: A Reference Bookshelf for an Occupational Health Service

- Index