- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Industrial Archaeology uses the techniques of mainstream archaeological excavation, analysis and interpretation to present an enlightening picture of industrial society.

Technology and heritage have, until recently, been the focal points of study in industrialization. Industrial Archaeology sets out a coherent methodology for the discipline which expands on and extends beyond the purely functional analysis of industrial landscapes, structures and artefacts to a broader consideration of their cultural meaning and value. The authors examine, for example, the social context of industrialization, including the effect of new means of production on working patterns, diet and health.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Industrial Archaeology by Marilyn Palmer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

The scope of industrial archaeology

The serious study of industrial archaeology is a phenomenon of the second half of the twentieth century, but even in that comparatively short period it has come to mean different things to different groups of people. Practitioners from backgrounds as diverse as public and private museums, railway preservation societies or canal restoration groups, and academics from a variety of disciplines as well as professional archaeologists and architects concerned with the recording of historic buildings would all class themselves as ‘industrial archaeologists’. Such a diversity of interests has resulted in a continuing debate concerning the scope of the subject but the general consensus now favours a definition of industrial archaeology as the systematic study of structures and artefacts as a means of enlarging our understanding of the industrial past. On the basis of this definition, the subject is now achieving a respectable professional standing not only in Britain but throughout the world. It has not yet, however, achieved a comparable academic standing, the result being that many of its practitioners have received no formal training in the specialist techniques required. The purpose of this book is to discuss these techniques in their wider archaeological context so that industrial archaeology can take its place in normal undergraduate courses to satisfy the demand for trained personnel to enter this new and exciting field.

THE ORIGINS OF INDUSTRIAL ARCHAEOLOGY

There have been various attempts to demonstrate that the term ‘industrial archaeology’ has its origins in the late nineteenth century, but it did not pass into popular usage until the mid-1950s in Britain. It arose out of a concern to record and even preserve some of the monuments of the British industrial revolution at a time of wholesale urban redevelopment. Its earliest champion was Michael Rix, whose work with Workers’ Educational Association (WEA) classes at the University of Birmingham highlighted the rapid transformation of the major iron and steel district of the Black Country. In an article entitled ‘Industrial archaeology’ in The Amateur Historian, he wrote:

Great Britain as the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution is full of monuments left by this remarkable series of events. Any other country would have set up machinery for the scheduling and preservation of these memorials that symbolise the movement which is changing the face of the globe, but we are so oblivious of our national heritage that apart from a few museum pieces, the majority of these landmarks are neglected or unwittingly destroyed.

(Rix 1955: 225)

Unlike previous industrial historians, Rix placed the emphasis firmly upon what could be learnt from the physical remains of industrialisation. His use of the term ‘archaeology’ inspired the Council for British Archaeology (CBA) in 1959 to set up a Research Committee on Industrial Archaeology and to call a public meeting, at which it was resolved that recommendations be made to national government urging the formation of a national policy for the recording and protection of early industrial remains. Before any formal action was taken, a significant monument from the earliest days of locomotive railways, the Euston arch, designed by Philip Hardwick as a triumphal entrance for the London terminus of the railway to Birmingham, was demolished. This caused a public outcry, and in 1963 the Industrial Monuments Survey was established jointly by the CBA and the Ministry of Public Buildings and Works. Rex Wailes became the first Survey Officer and a basic index record was begun, known as the National Record of Industrial Monuments (NRIM). From 1965 this passed under the direction of R. A. Buchanan in the Centre for the Study of the History of Technology at what was later to become Bath University. The data collected was not, however, transferred to the county Sites and Monuments Records, which were themselves in their infancy, and this transfer is only now beginning to take place in the 1990s.

The Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments of England (RCHME) had included some industrial buildings such as malthouses and watermills in its county inventories, but was then working to a cut-off date of 1700. In Scotland, on the other hand, nineteenth-century industrial buildings had been included in the county inventories prepared in the 1950s by the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland (RCAHMS) at the instigation of the then secretary to the commission, Angus Graham. This emphasis on compiling lists of industrial sites was also reflected in the earlier publications on industrial archaeology, many of which took the form of regional gazetteers, but little attempt was made to prioritise these sites on a national basis. From the late 1960s, however, a number of industrial monuments were added to the schedules, largely as a result of recommendations from the CBA's Advisory Panel which considered lists of sites prepared by the Survey Officer and others on either a thematic or a regional basis. The scope of the thematic surveys depended on the interests of the volunteers prepared to undertake them, and included lighthouses, water-raising by animal power and existing steam plant in water supply, sewage and drainage pumping stations. While creating a valuable record, the scope of these thematic surveys was obviously highly selective and did not enable the majority of sites to be placed in their context. The Industrial Monuments Survey, then the responsibility of Keith Falconer, followed the NRIM to the University of Bath in 1977 and both were transferred to RCHME in 1981. From a national point of view, then, the CBA was the first archaeological organisation to espouse this new aspect of archaeology but did not altogether maintain its interest, whereas the Royal Commissions were slightly later in the field but have been responsible for maintaining and developing the records created in those early years.

The Newcomen Society, which was formed in 1920 to pursue the study of the history of engineering and technology, encouraged the new discipline to the extent of supporting the Journal of Industrial Archaeology, first published in 1964. A series of annual conferences, mainly at the University of Bath, resulted in 1973 in the foundation of the Association for Industrial Archaeology (ALA) with L. T. C. Rolt as its first president. The aims of this organisation were to encourage improved standards of recording, research, conservation and publication as well as to assist and support regional and specialist survey and research groups and bodies involved in the preservation of industrial monuments. The AIA in 1976 launched Industrial Archaeology Review, first published by Oxford University Press but becoming the AIA's house journal in 1984 and now the only surviving national journal in the discipline. The aims of the AIA reflect the dichotomy within industrial archaeology between research and preservation, which has perhaps hindered its acceptance as an academic discipline. Recently, however, the Association has played a much greater role in influencing national trends in industrial archaeology, notably through its publication of a policy document entitled ‘Industrial archaeology: working for the future’ (Palmer 1991) which stated the objectives of industrial archaeology in the 1990s and offered recommendations for their implementation.

At the local level, the cause of industrial archaeology was taken up by a variety of people who all brought their own particular skills and expertise to bear on the subject. It flourished in university adult education and WEA courses, while numerous preservation groups were established to maintain monuments, particularly those containing prime movers such as waterwheels and steam engines. The cultural resource management of industrial sites in Great Britain will be discussed in Chapter Seven, although some mention is made of the international dimension of the conservation movement in this chapter. The landscape, however, is not a static environment; it is constantly evolving and to conserve more than a selection of the physical evidence of the industrial past is neither possible nor desirable. Preservation is only part of industrial archaeology, and its main thrust should be towards the recording of artefacts and structures and illuminating the context of people at work in the past. This balance has not always been achieved, but the over-emphasis on monuments is now disappearing and industrial archaeology can now take its place as a fully fledged branch of archaeological studies if it will at the same time accept the need for a research agenda with a theoretical content.

INDUSTRIAL ARCHAEOLOGY AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL THEORY

Industrial archaeology became an accepted area of study in the 1960s at the same time as archaeology itself was adopting a more theoretical stance. Yet, as E. G. Grant has said:

Industrial archaeology has neglected almost all theory in some kind of mistaken belief that it could approach the material remains of industrial society with no particular methodological or explanatory framework.

(Grant 1987: 118)

It is undoubtedly true that much of the work carried out in industrial archaeology has been of a descriptive rather than an analytical nature, concentrating on the physical remains of past industries as entities in themselves rather than as expressions of human endeavour. Or, as Matthew Johnson has put it: ‘most work in this area has concentrated on the archaeological elucidation of the development of the technologies involved rather than the social and cultural parameters’ (Johnson 1996: 12). This is partly because much of the work undertaken in industrial archaeology, as in post-medieval archaeology, has been small-scale site work which has not been susceptible to the generalisations beloved of processual archaeologists. Explanations have often been limited to site-specific ones framed in an historical mode, in the belief that if all the details leading up to the establishment of a site or structure are known, this is in itself sufficient explanation. Industrial archaeology has hitherto lacked a broader research agenda and has rarely tried to contribute to wider historical debates, e.g. on the origins and effects of industrialisation.

If the ‘new archaeology’ did nothing else, it taught archaeologists to approach both fieldwork and the analysis of data with a series of often complex questions in mind. But the data of industrial archaeology is generally limited to the physical remains of sites and structures plus map, documentary and photographic evidence; what is nearly always lacking is normal artefactual material for analysis. There are large numbers of industrial museums which all display artefacts, often in their social context, but no real attempt has been made to build up reference collections of pottery, glass, metal artefacts, slags, etc. Few British archaeologists working on sites of the industrial period have treated artefacts in the same way as, for example, historical archaeologists in America or Australia (Deetz 1977; Glassie 1975). The stratigraphy of artefacts on industrial sites has rarely been noted, and the assemblages have been discarded rather than preserved. If we accept that material culture is meaningfully constituted, we therefore lack the raw data from which to extract those meanings. Even the documentary sources so successfully used by Lorna Weatherill to determine consumer behaviour in early modern Britain (Weatherill 1988) are more fragmentary for the industrial period, which makes it even more important to take note of artefacts. An example of how consumer attitudes can be inferred even from contemporary articles of material culture is the comparative work carried out by Shanks and Tilley on the design of contemporary beer cans in Britain and Sweden, which can be shown to indicate the differing attitudes of the two countries towards the consumption of alcohol (Shanks and Tilley 1987). Despite the problems of retaining the often vast assemblages derived from sites of the recent past, some attempt should be made both to build up reference collections of basic types of artefacts and to use the data as evidence of the material culture of the period.

Industrial archaeologists at present, therefore, concentrate on the interpretation of sites, structures and landscapes rather than artefactual material. This does not, of course, mean that they are excused from working within a theoretical framework but that the data used is rather different from that of the prehistoric archaeologist. The various approaches used by archaeologists are intended to provide a means of extracting the maximum information from material remains by making observations within a framework of inference. Yet industrial archaeologists have usually contented themselves with a functional analysis of sites and structures, or by giving them an economic or technological context. The necessity of locating the earliest example of a particular process, or the most complete surviving site for the purposes of listing and scheduling, as discussed earlier, has inevitably led to an approach which concentrates on the positive aspects of human progress and therefore has much in common with the processual school of the new archaeology. Yet the majority of sites in the industrial period provide structural evidence for the social upheaval and redefinition of the class system which accompanied the process of industrialisation. A Marxist approach would be more appropriate in many cases, since the period under study certainly witnessed contradictions between the forces and the relations of production, i.e. between capitalist organisation utilising new technology and the social organisation of the workforce who were forced to adapt to a new working and often also a new domestic environment. Looked at in this way, the introduction of a new steam engine to a previously water-powered mill, a common phenomenon in the nineteenth century which can be identified both from physical and documentary evidence, probably involved the workforce both in learning new skills and also in more rigorous shiftwork, since the owner would wish to recoup his capital expenditure by keeping the engine working on a continuous basis. The resolution of this conflict between the new technology and the social organisation of the workforce which operated it would be, in Marxist terms, an example of the way in which society advanced.

Of course, not all sites of the industrial period lend themselves to this kind of approach. Many mundane structures, such as lime-kilns or buddies, seem far removed from conflicts within human society. They have usually been examined typologically to assess technological development (Palmer and Neaverson 1989; Stanier 1993), yet any industrial structure is not an isolated monument but part of a network of linkages relating to the methods and means of production. In these instances, Ian Hodder's use of ‘contextual archaeology’ is relevant, ‘the full and detailed description of the total context as the whole network of associations is followed through’ (Hodder 1986: 143). These associations include not only the economic ones of sources of raw materials, methods of processing and transport networks which industrial archaeologists do normally consider, but also the social context of production. Industrial archaeologists have the advantage of documentary as well as material evidence, and should not be afraid to use it to help explain the sites and structures with which they are dealing. The social context of production has frequently figured in the display material accompanying museum or conservation projects, but has less often formed part of the agenda for recording industrial sites. It is, however, a vital element in understanding the relationship between the different components of complex sites and also their social symbolism.

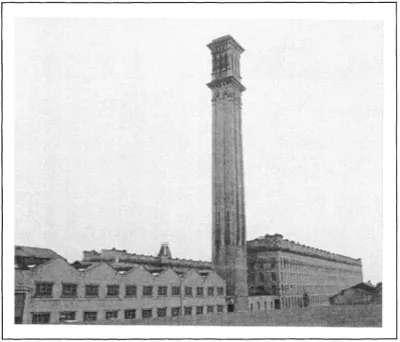

From the point of view of the entrepreneur, his industrial empire could be used as a vehicle for the expression of personal prestige. The mill-owner adopted new fashions in architecture, from the Palladianism of the late eighteenth century to the Gothic and Italianate traditions of the late nineteenth. Boulton and Watt in 1765 employed Benjamin Wyatt to design their manufactory at Soho, Birmingham, which for a time became the largest of its kind in Europe. The Palladian façade disguises the more mundane reality of the forges, rolling mills and other aspects of the production carried out by this international firm. The Italianate style became popular for textile mills in the north of England, where several magnificent mill chimneys were modelled on Italian campaniles. A supreme example is Manningham Mill in Bradford (Plate 1), designed by local architects for Messrs Lister, manufacturers of velvet and other fancy cloths. The six-storey mill, with its campanile chimney 249 feet [75.9 metres] high, dominated the Bradford skyline, and enabled its owners to maintain their position in relation to other local entrepreneurs such as Sir Titus Salt, whose model community and huge mill had been built twenty years before. Similar fashions were also often adopted in the homes of the mill-owners: the wealthy cotton-spinning family, the Fieldens of Todmorden, had the vast pile of Dobroyd Castle constructed for themselves in the 1860s as well as providing their town with a town hall, the scale of which was designed to reflect their own prestige rather than to be in keeping with the rest of its buildings. These symbols of power are as important to the understanding of the dynamics of nineteenth-century society as the personal possessions of the elite are to that of Bronze Age Wessex.

Plate 1 The dominant Italianate chimney stack of Manningham Mill, built 1871–3 on a hilltop site, which helped to establish Lister's as a landmark in Bradford, West Yorkshire.

Many industrial sites developed over time as sources of power and methods of technology changed, and have primarily been analysed in these functional terms. But these sites can also indicate the changing social dimensions of production, the landscape of weavers’ cottages with isolated fulling mills representing a different type of organisation from that of Sir Titus Salt's model community of Saltaire (Plate 2). The spatial layout of the purpose-built industrial complex, which was typical of much industrial society from the late eighteenth century onwards, shows how time was regulated in the interest of the maximisation of profit. Continuous production, whether pow...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Industrial Archaeology

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of plates

- List of figures

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- List of abbreviations

- Chapter One THE SCOPE OF INDUSTRIAL ARCHAEOLOGY

- Chapter Two LANDSCAPES AND TOWNSCAPES

- Chapter Three BUILDINGS, STRUCTURES AND MACHINERY

- Chapter Four FIELD TECHNIQUES

- Chapter Five DOCUMENTARY RESEARCH

- Chapter Six INDUSTRIAL ARCHAEOLOGY IN PRACTICE

- Chapter Seven CULTURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT OF THE INDUSTRIAL HERITAGE IN BRITAIN

- Bibliography

- Index