- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Resistance and social movements in mental health have been important in shaping current practice in both mental health and psychiatry. Contesting Psychiatry, focusing largely on the UK, examines the history of resistance to psychiatry between 1950 and 2000. Building on the author's extensive research, the book provides an empirical account and exploration of the key features including:

- an account of the key social movements and organizations who have contested psychiatry over the last fifty years

- the theorization of resistance to psychiatry which might apply to other national contexts and to social movement formation and protest in other medical arenas

- the exploration of theories of power in psychiatry.

Original and provocative in its approach, this book offers a new sociological perspective on psychiatry.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Contesting Psychiatry by Nick Crossley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Health Care Delivery. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Social movements, SMOs and fields of contention

I have stated that the primary focus of this study is the UK field of psychiatric contention between 1950 and 2000. In this brief chapter I will define in more detail what I mean by ‘field of contention’ and by the related concepts ‘social movement’ and ‘social movement organisation’ (SMO). My understanding of each of these concepts is derived from a critical dialogue with the ideas of Zald and McCarthy (1994). As representatives of the ‘resource mobilisation’ (RM) approach to social movement analysis, Zald and McCarthy are often criticised and dismissed in contemporary social movement analysis. Much of the criticism is justified in my view and I have added my own contribution to their critique (Crossley 2002a). Beyond the problems, however, there is something appealing about their model which makes it a good place to start thinking about ‘social movements’ and more particularly ‘fields of contention’. We need to reconstruct their ideas but they provide an instructive point of departure. I begin, therefore, with Zald and McCarthy.

Zald and McCarthy’s field model

For Zald and McCarthy (1994) a ‘social movement’ is a vague current of collective sentiment within some part of society which expresses a demand for either change or resistance to change. There might be a feeling amongst some members of the general population, for example, that an activity of state, such as a war, is unacceptable. That would be a ‘social movement’ by this minimalist definition.

In addition, Zald and McCarthy continue, we sometimes find sentiments and demands which oppose those of a social movement. Other members of the population, for example, might think that war is justified and that opposition to the war is itself wrong for reasons, of being unpatriotic. This, in Zald and McCarthy’s terminology, is a ‘counter-movement’. Counter-movements oppose whatever it is that movements call for. They call for something different and usually something opposite. Thus we have both pro-choice and anti-abortion movements, fascists and anti-fascists, pro- and anti-hunting lobbies etc. I will be challenging the notion that contention between competing currents of opinion always breaks down into ‘pro’ and ‘anti’ camps later, and I will be suggesting that the concept of counter-movements is problematic for this reason. For present purposes, however, let’s stick with these terms.

Zald and McCarthy do not clarify the nature of these sentiments and demands but I suggest, in opposition to what I think they would suggest, given their underlying theoretical orientation,1 that we can think of them in terms of a communicative model. Social agents form opinions by means of interaction with others, both in their personal social networks, in institutional networks such as the church or workplace and by way of the broadcast networks2 of the mass media. Interactions and the wider networks they comprise are the means by which ideas are both generated and passed on so as to become collective in the manner of a social movement.

Movements and counter-movements are of less interest to Zald and McCarthy, however, than the SMOs which take shape within them and which ‘carry’ them. Social movements, as Zald and McCarthy define them, do not and cannot do very much. They are not agents or actors (see Melucci 1989). In order for their sentiments to be expressed and translated into action they must be taken up by SMOs. Zald and McCarthy’s model of SMOs is quite explicitly economic in inspiration. The relationship of SMOs to movements is one of ‘supply’ to ‘demand’. Movements ‘demand’ expression and action, SMOs supply that expression and action in return for some form of ‘payment’, whether in the form of the symbolic support and recognition of ‘adherents’, who share the view of an SMO, or the more material contributions of ‘constituents’, who donate money and other tangible resources and who may become directly involved in the actions organised by SMOs. As in economic markets, this relationship can be either supply or demand led and will often involve an element of both. The formation of SMOs is often a response by political entrepreneurs to pre-existing problems (supply is generated to meet pre-existing demand). Equally, however, political entrepreneurs and their SMOs can seek to generate demand by trying to sell a problem and their solution to it. In either case, however, SMOs seek to draw individuals from the general population into their pool of adherents, and they seek to draw adherents into their pool of constituents.

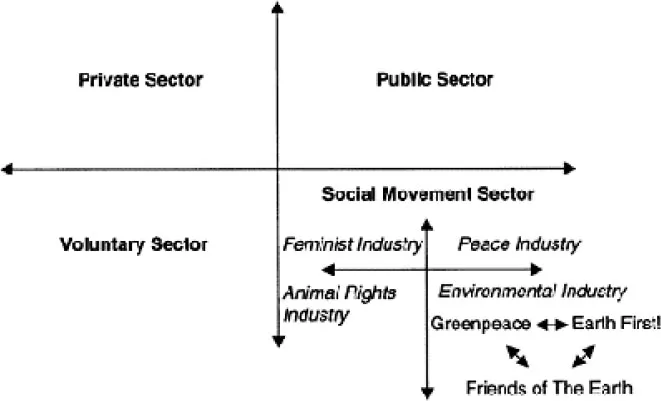

Any social movement, Zald and McCarthy continue, will tend to generate more than one SMO. Thus, within environmentalism, to name only the most obvious, we have Greenpeace, Friends of the Earth, Earth First!, Reclaim the Streets and The Earth Liberation Front. Zald and McCarthy refer to these clusters as industries, arguing both that SMOs within industries compete with one another for resources and support and that this dynamic of interaction and competition is crucial to a proper understanding of contentious politics. ‘All of the SMOs of a social movement industry’, they argue, ‘must be seen as part of an interacting field? (Zald and McCarthy 1994, 120, my emphasis). And it is this field which should form the central point in analysis.

Extending this point Zald and McCarthy argue, first, that there is competition among industries in what they call ‘the movement sector’. The feminist industry, for example, must compete with the environmental and mental health industries for a finite pool of resources and support. Potential constituents have limited resources and cannot donate to every SMO or even to SMOs representing every worthy movement ‘industry’ or cause. They must be selective and this pressure upon them generates pressure between SMOs and industries who must compete to be selected. Second, they argue that the movement sector itself competes with the public, private and voluntary sectors of the economy. Agents who might give their resources to an SMO might also spend those resources on private goods, such as consumer durables, for example, or these resources might be absorbed through increased taxation within the public sector. How the sector and its component industries and SMOs fare is dependent upon its relationship to these other sectors. This links movement activism into the wider economic dynamics of society. Zald and McCarthy argue, for example, that there is evidence to suggest that movement activity increases during periods of affluence, and they seek to explain this by arguing that resources tend to be used for essential purchases in the private and public sectors during times of economic hardship, tending only to be freed up for the ‘luxury’ of donating to movements during periods of economic upturn. Figure 1.1 maps out the various successive layers of SMOs, industries and sectors described by Zald and McCarthy.

Underlying this model is the key claim of the RM approach to social movement analysis; namely, that political mobilisation presupposes a mobilisation or utilisation of scarce resources. That is why SMOs pursue constituents. Furthermore, this claim has the important implication that political mobilisation (or at least successful mobilisation) is said to be dependent upon resource flows and thus to fluctuate with the fluctations in resource flows. When the resource flow into an SMO, industry or the movement sector more generally increases, we can expect levels of contention to rise. When the flow dries up, so too will the contention.

Figure 1.1 Zald and McCarthy’s model illustrated (and simplified).

Although I believe that RM theorists overestimate the significance of resource flows, they clearly have a point. We certainly need to consider resource mobilisation when we start to think about how we might explain the dynamics of contentious politics. What I find most interesting about the work of Zald and McCarthy, however, is their concept of fields. The concept of fields of interacting SMOs, linking to and competing for adherents and constituents is very persuasive in my view and forms the basis of my own concept of ‘fields of contention’. It identifies an irreducible level of contentious politics, both in the concept of SMOs and the field constituted through their interaction. Insofar as SMOs have specific procedures for making and executing decisions we may, following Hindess (1988), grant them a status as (‘minimal’)3 agents in their own right but this does not commit us to a view, much criticised in the literature, of ‘movements’ as collective actors or subjects (see Melucci 1989 for a critique of this view), not least because SMOs are not movements and, in any case, are situated in a field of social relations and interactions. It is this field which is our primary focus of analysis. The field, moreover, is irreducible and relational. The action of each agent within it, whether an individual, an SMO or some other organisational actor, responds to and anticipates the actions of at least some of the others, who do the same, such that no agent can be understood independently of the processual and interactive dynamics of the field as a whole. In addition, Zald and McCarthy encourage a dissection of contentious politics which the notion of ‘movements’ sometimes obscures. Whilst drawing ‘the whole’ into focus they simultaneously identify the division of labour and competitive tensions between its constituent parts. If the whole is greater than the sum of its parts this is only in virtue of the interdependencies and interactive dynamics between them. The moment one becomes acquainted with a movement, the existence of these ‘parts’ is often obvious but Zald and McCarthy are relatively rare in seeking to explore their interdependency.

There are problems with the model, however. I have spelled these out in detail elsewhere (Crossley 2002a). Here I will outline a few key problems. They come in three batches. The first relates to the economism of the model, the second to questions of culture and the third to issues of structure.

The problem of economism and rational action

The market model evoked by Zald and McCarthy offers an image of individual entrepreneurs appealing to the demands or generating demand from a mass of individual consumers. This is problematic on a number of levels. In the first instance it overlooks the importance, in at least some cases, of social networks. Here, the example of the black civil rights movement in the United States, is illustrative. The early SMOs of the movement grew out of community networks which were rooted in black churches and colleges and often preserved the organisational hierarchies (e.g. ministers as activist leaders) and cultural forms (e.g. hymn singing and hand holding) of those communities. Moreover, these SMOs sought ‘block recruitment’ from amongst congregational and student bodies, rather than individual recruits. Networks rather than individuals were the key ‘building blocks’ of this movement. This is not true of all movements, of course. One need only open a national newspaper for evidence of SMOs, such as Greenpeace, making appeals to individuals for money and support. And there is evidence that these professional ‘mail order’ SMOs have increased their ‘market share’ in recent years (Putnam 2000). Indeed Zald and McCarthy themselves make this case. However, we should at least be aware that the individualistic assumptions of Zald and McCarthy’s model do not always hold, and we should be aware of a need to be able to think in more collective and relational ways.

Second, the idea of economic rationality, which, in the guise of rational action theory (RAT), guides Zald and McCarthy’s model, is deeply problematic (Crossley 2002a, Feree 1992, Hindess 1998). It is difficult to deny that there is an element of truth to RAT. It is to the advantage of activists to pursue and use scarce resources in an efficient manner and most will tend to do so. Moreover, human action is purposive. It pursues goals. If one defines ‘goals’ as ‘rewards’ then much human action is, by definition, the pursuit of ‘rewards’. The RAT model pushes this too far, however, claiming that ‘rewards’ are necessarily individual, selfish, material and stable over time-none of which is necessarily true (see Crossley 2002a). Moreover, it tends to ignore the role of interpretation in cognition and to presuppose, unrealistically, both ‘perfect’ information and extremely refined mechanisms of information processing, priority setting, strategising and tactical deliberation on behalf of social agents. This is problematic on many levels and fails to account for much of what we find in social movements. Indeed it fails to account for much of what Zald and McCarthy refer to in their own model. The selfish materialism of the approach, for example, fails to explain the often principled and altruistic demands of social movements: for example, humane treatment of animals, protection of the planet for the sake of future generations and the welfare of fellow human beings in distant societies. Why would selfish materialists be bothered about such ends? Furthermore, in their discussion of ‘constituents’ Zald and McCarthy accord a high priority to those who contribute resources to movements on the basis of conscience (‘conscience constituents’). This is hardly rational economic behaviour!

We could push the point further by considering some of the considerable acts of self-sacrifice made by activists. From suicide bombers and hunger strikers through tunnelers and tree house dwellers4 to the nameless many who stuff envelopes for ‘lost causes’, social movement activism throws up numerous examples of agents who give a great deal without much expectation of reward, certainly not in a material sense. Some RAT advocates deflect such criticism, claiming to find ‘profit’ in self-sacrifice, but their defences make the theory circular, as any goal becomes profitable and selfish, by definition. The further consequence of this is that the testable aspect of the theory, one of its virtues, celebrated by many of its advocates, is lost too (Crossley 2002a).

I suggest that we abandon RAT. We should stick with the idea that resources are important and will therefore often be sought after. We should also stick with the idea that human action pursues goals and, under most circumstances, seeks to maximise ‘goods’ and minimise ‘bads’. But we should avoid carrying that to the absurd lengths of RAT. And we should allow ourselves a model of human agency which is richer and includes the many obvious human attributes and tendencies (socially generated and/or shaped in many cases) ignored by RAT including interpretation, conscience and even a sense of humour.

For similar reasons, I suggest that we relax the definition of SMOs suggested by Zald and McCarthy. Any large social movement involves multiple discrete networks, groups and organisations but by no means all of them conform to the model of economically rational organisation suggested by Zald and McCarthy (1994), and we overlook much of what is interesting about them if we assume that they do. I would rather think of an SMO as any group, network, organisation or collective project which has a discrete identity within a field of contention; that is, a collective formation that either thinks of itself as distinct or is recognised and known as such in the field. Usually this will be a named collective but often it will not be a ‘rational’ organisation, in the utilitarian sense. Indeed, in some cases it will involve collectives whose members strive to organise themselves in ways which depart from and resist the assumptions of a rational economic or political model.

Cultures of contention

In some of their work Zald and McCarthy concede that they are too economistic. We need a more cultural model they suggest:

Although we think the parallel with economic processes is striking, we should remember that there are differences. In particular, competition for dominance amongst SMOs is often for symbolic dominance, for defining the terms of social movement action. Social movement leaders are seeking symbolic hegemony. At some point social movement analysis must join with cultural and linguistic analysis if it is to understand fully cooperation and conflict in its socially specific forms.

(Zald and McCarthy 1994, 180)

I couldn’t agree more. Zald and McCarthy do not develop this aspect of their argument, however. We must. We need to be mindful that interaction within fields is generative of a movement discourse and culture; that is, of norms, identities, symbols, frames, typifications and a range of stories and sacred texts which identify heroes, villains, promised lands etc. This is not to say that members of a field agree about such matters but, as Bourdieu (1993) says in his conception of fields, they at least agree sufficiently to have something to disagree about. We need to be mindful of this cultural dimension in our investigation of fields of contention, following through on what Zald and McCarthy fail to deliver. I address this further in Chapter 2.

Structure

A further problem with Zald and McCarthy’s model is their failure to identify that and how network patterns take shape within fields which structure those fields and which, potentially at least, have significant effects. I agree with Zald and McCarthy that SMOs interact and that these interactions are constitutive of (what I call) fields of contention but I want to take this further, following the lead of DiMaggio and Powell (1983), by noting that this does not entail every SMO interacting with every other SMO. Certain SMOs interact with certain others. More to the point, SMOs will interact in certain ways, giving rise to certain forms of relationship, with certain of their fellow SMOs, relating to others in other ways and perhaps not really relating at all to others still. Potentially there may be a great deal of fluidity involved here. I have used the term ‘interaction’ alongside ‘relationship’ in an attempt to indicate that relationships have to be ‘done’ and can be ‘undone’. New relationships form; old ones sometimes die out. They are always ‘in process’. Indeed a field i...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction Researching resistance

- 1: Social movements, SMOs and fields of contention

- 2: A value-added model of mobilisation

- 3: Contextualising contention A potted history of the mental health field

- 4: Mental hygiene and early protests 1930–60

- 5: Anti-psychiatry and ‘the Sixties’

- 6: Parents, people and a radical change of MIND

- 7: A union of mental patients

- 8: Networks, survivors and international connections

- 9: Consolidation and backlash

- Notes

- Bibliography