![]()

Helping You Understand Dr. Goldstein's Book

Dr. Goldstein's book, Betrayal By The Brain: The Neurologic Basis of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, Fibromyalgia Syndrome, and Related Neural Network Disorders, can be a daunting treatise to the layperson as well as a challenge for the physician who is not versed in neurology, psychiatry, immunology, and endocrinology—all specialty fields in their own right.

In reading Dr. Goldstein's book, it becomes apparent that he has drawn upon the research findings of many of his colleagues and, along with his extensive clinical experience of over 12 years and 4,000 patients, has synthesized what he refers to as an "integrative hypothesis" to suggest the pathophysiology of both fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndromes.

Here we will try to present enough of the salient points of the book so that you can understand the underlying concepts. We will also offer a Glossary of words and acronyms you will come across frequently as you read the book.

To the layperson, probably the most compelling evidence lies within Dr. Goldstein's case reports. It becomes less important for the suffering patient to understand why the drug protocol works, but simply that it does work for so many people.

To begin an understanding of Dr. Goldstein's theories, it is important to understand the roles of brain structures and the neurochemicals that interplay to create the complex constellation of symptoms we know as CFS and FMS.

First, we will describe the proper role and function of each brain structure or neural assembly that plays a role in neurosomatic disorders, and then we will describe its apparent dysfunction. Where applicable, we will mention drug therapies that Dr. Goldstein has found to modulate the functioning of these structures or networks to produce symptom relief. All drug names appear in italics.

Understanding the following terms will help as you read about the various structures of the brain. This nomenclature describes the location of brain structures in relation to one another.

Brain Structures

Amygdala

Normal Function—Part of the limbic system, the amygdala is a small mass of gray matter lying in the roof of a lateral ventricle (see Glossary). The job of the amygdala is to receive input from the neocortex (the dorsal [posterior] region of the cortex) and to integrate external events with internal signals. The amygdala is also important in memory encoding, particularly for the ability to recall facts.

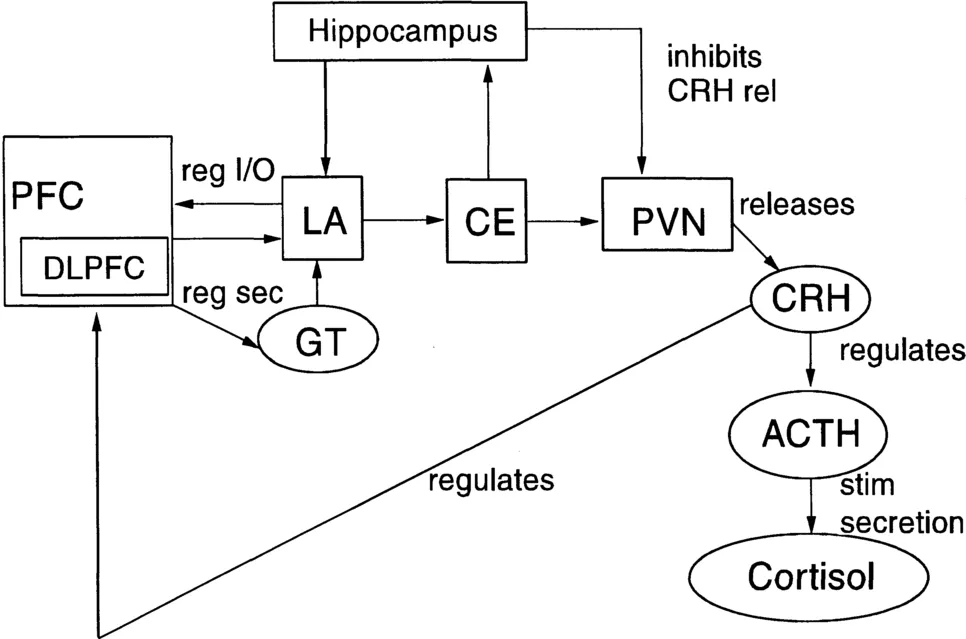

The amygdala's role in auditory fear conditioning is a subject of recent study. Auditory stimuli reach the acoustic thalamus and travel from there to the lateral amygdala (LA) directly or through the specialized auditory cortex within the cerebral cortex. The LA receives data through connections from the hippocampus regarding the "context" (i.e., the environmental and experiential factors surrounding the input), which helps shape the organism's response. The arbiter of this response is the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC). This contextualized input with DLPFC interpretation then continues from the LA to the central nucleus of the amygdala (CE) for processing. The CE then projects to the areas of the brainstem that control the response of the hippocampus, resulting in both voluntary and involuntary actions by the organism. The CE also projects to the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN), another component of the limbic system. The PVN is responsible for the release of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), which stimulates the release of Cortisol through its regulation of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH).

Dysfunction in CFS/FMS—The prefrontal cortex (PFC) regulates amygdalar input and output. A certain location within the PFC, the DLPFC, appears dysregulated. The DLPFC misinterprets the contextualized input coming from the amygdala and hippocampus and perceives it as a novel cognitive situation rather than a known cognitive routine, resulting in an inappropriate stress response.

Decreased secretion of glutamate from the prefrontal cortex to the lateral amygdala may result in a decrease of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) levels in the central nucleus of the amygdala.

When negative outcomes become expected and the subsequent arousal from fear and threat becomes chronic, depression and/or anxiety usually follow, accompanied by activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and elevation of stress hormones such as Cortisol. This expectation of fearful events causes activation

Brain structures appear in boxes; neurochemicals in ellipses.

of the amygdala, hi disorders such as depression, schizophrenia, and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), increased CRH levels in the central nucleus of the amygdala accompany this activation, setting the stage for chronic arousal and its deleterious effects. The amygdala, brainstem, and hypothalamus comprise the neural network that activates the CE CRH release, facilitated by substances called glucocorticoids (such as Cortisol). Chronically elevated levels of glucocorticoids (like Cortisol) can damage hippocampal neurons, producing further levels of PVN CRH because they alter the ability of the hippocampus to inhibit levels of CRH. Obviously, another mechanism must be at work in neurosomatic disorders in which CRH levels are low. (See the section on the hippocampus for Dr. Goldstein's theory.)

Basal Ganglia

Normal Function—These groups of nerve cells sit above the brainstem and next to the limbic system in each hemisphere of the brain. The caudate nucleus, which is part of the basal ganglia, together with the cerebellum, helps maintain balance and coordinate complex body movements, including starting and stopping motion and producing smooth, flowing muscular action. The basal ganglia also play a role in encoding procedural, or skill memory.

Along with its role in coordinating motor functions, the basal ganglia may be the most important structure for nociception (the mechanism by which we perceive painful stimuli). The basal ganglia processes information about noxious and nonnoxious sensory stimuli. The basal ganglia receive this information from nociceptive neurons that cover wide receptive fields, sometimes including the entire body (unlike specialized sense organs such as the eyes and ears). These neurons carry information about the intensity of the stimulus but not its location.

Specialized neurons within the striatum of the basal ganglia may act as sensory gates and contribute to the determination of information saliency and the corresponding motor response.

Studies of injuries to the structures of the basal ganglia demonstrate its link to mood regulation. In most of these disorders, like Parkinson's disease, a motor disorder often accompanied by pain and depression, lack of dopamine plays a major role, along with low levels of serotonin and norepinephrine.

The caudate nucleus of the basal ganglia and the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) are the primary anatomical structures involved in producing slow-wave-sleep.

Dysfunction in CFS/FMS—Hypoperfusion (reduced cerebral blood flow) is evident in the right caudate nucleus of neurosomatic patients. There is a direct correlation between the degree of hypoperfusion and the patient's level of pain.

Because of the wide receptive fields of neurons within the basal ganglia, it is possible that they play a role in the diffuse, bodywide pain perception of FMS.

A very complex neural network loop appears to exist, with relevance to cognitive function, connecting the prefrontal cortex (PFC), the structures of the basal ganglia, and the thalamus. It is the CSTC, or cortico-striatalthalamo-cortical loop. Stated very simplistically, in neurosomatic disorders, reduced function of the PFC and caudate nucleus of the basal ganglia combine with increased inhibition in the thalamus to decrease "thalamocortical excitation." Dysregulation of glutamate, gamma-amino butyric acid (GABA), and dopamine all play a part. Dr. Goldstein speculates that this reduced "thalamocortical excitation" may be the underlying cause of neurosomatic disorders.

Problems with mood regulation are a major component of neurosomatic disorders and the basal ganglia may be the locus of control. Both depression and mania have a link to reduced function of the caudate nucleus. Injury to the structures of the basal ganglia can cause apathy, depression, mania, uninhibited behavior, obsessive-compulsive-disorder, Tourette's syndrome, irritability, and amnesia, among other symptoms. Interestingly, however, many CFS/FMS patients do not experience depression, and disorders falling within the obsessive-compulsive spectrum are uncommon. From a functional standpoint, in many respects, OCD's are the opposite of CFS/FMS.

Reduced dopamine levels in the cerebrospinal fluid are likely due to reduced glutamate secretion from the PFC to the ventral tegmental area (VTA) of the caudate nucleus that releases dopamine. Reduced dopamine levels in the VTA may produce anxiety.

A dysfunction in the caudate nucleus of the basal ganglia could affect the onset and duration of restorative slow-wave sleep, a common problem in neurosomatic disorders.

Drug Remediation—The use of dopamine agonists (drugs designed to increase levels of dopamine or prevent its reuptake) are ineffective in neurosomatic patients.

Cerebellum

Normal Function—Located just below and outside the cerebral hemispheres and behind the brainstem, the cerebellum, or "small brain," is the center for the control and coordination of movement. The cerebellum monitors a "map" of the body's position and location and controls the process of "proprioception," by which the body knows where it is and where it is going. Through its connections to the brainstem, the cerebellum receives information from receptors in the skin, muscles, joints, tendons, and the balance mechanisms of the inner ears. When the central nervous system orders a movement to occur, the cerebral cortex activates a "program" of learned patterns of motion carried within the cerebellum. The cerebellum then continuously monitors the body, particularly its posture and state of muscle contraction or relaxation. Working with the caudate nucleus that is part of the basal ganglia, the cerebellum then corrects any discrepancies between the "program" and what the body is actually doing, producing smoothly coordinated body movements and maintaining posture and balance. The cerebellum also plays a role in encoding procedural, or skill, memory.

The above description represents the traditional, textbook view of the cerebellum as a motor mechanism. However, when viewed with functional brain imaging, the cerebellum is also active during cognitive and language tasks. The neodentate, a recently evolved part of the cerebellum, which has grown very large in humans, has as its target structures the brainstem, thalamus, and the cerebral cortex. Its primary target, however, is the frontal lobe, particularly the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) and Broca's language area in the inferior prefrontal cortex. Broca's area is active in the process of word finding, a function often difficult for CFS/FMS patients. Two-way communications exist between the cortex and the cerebellum, facilitating coordination in performing cognitive and language tasks. Studies imply that the neodentate performs "counting, timing, sequencing, predicting and anticipatory planning, error detecting and correction, shifting of attention, pattern generation, adaption, and learning" (Goldstein, 1996, p. 97); many of the functions impaired in neurosomatic disorders.

Dysfunction in CFS/FMS—PET scan (functional brain imaging) has revealed baseline hypometabolism (reduced metabolism) in certain locations within the cerebellum.

Generally, Dr. Goldstein has not seen evidence of cerebellar dysfunction, either through functional PET scanning or SPECT scanning in CFS/FMS patients; however, he believes that the cerebellum and its associated neural network are likely contributors to the cognitive difficulties found in neurosomatic disorders.

Dr. Goldstein conceives of hypofunction (reduced function) occurring in the cerebellar-locus ceruleus pathway of CFS/FMS patients, due to reduced LC function, resulting in difficulty filtering out irrelevant sensory stimuli.

Cerebral Cortex

Normal Function—The outer layer of the brain, the deeply convoluted cerebral cortex known as "gray matter," makes up about 40 percent of the brain's total weight. One of the functions of this region is to store memories. The cortex is divided into two hemispheres connected by the corpus callosum, allowing an individual to function as a coordinated whole. There are specific regions of the cortex associated with certain senses: the sensory cortex receives signals from the skin, bones, joints, and muscles, producing the sensations of touch and pressure; the visual cortex receives signals from the optic nerve; other less specific cortical regions receive signals regarding hearing, smell, and taste sensations.

In addition to sensor...