eBook - ePub

Animation Writing and Development

From Script Development to Pitch

- 360 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The art. The craft. The business. Animation Writing and Development takes students and animation professionals alike through the process of creating original characters, developing a television series, feature, or multimedia project, and writing professional premises, outlines and scripts. It covers the process of developing presentation bibles and pitching original projects as well as ideas for episodes of shows already on the air. Animation Writing and Development includes chapters on animation history, on child development (writing for kids), and on storyboarding. It gives advice on marketing and finding work in the industry. It provides exercises for students as well as checklists for professionals polishing their craft. This is a guide to becoming a good writer as well as a successful one.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction to Animation

What Is Animation?

The word animate comes from the Latin verb animare, meaning “to make alive or to fill with breath.” We can take our most childlike dreams or the wackiest worlds we can imagine and bring them to life. In animation we can completely restructure reality. We take drawings, clay, puppets, or forms on a computer screen, and we make them seem so real that we want to believe they’re alive. Pure fantasy seems at home in animation, but for animation to work, the fantasy world must be so true to itself with its own unbroken rules that we are willing to believe it.

Even more than most film, animation is visual. While you’re writing, try to keep a movie running inside your head. Visualize what you’re writing. Keep those characters squashing and stretching, running in the air, morphing into monsters at the drop of an anvil! Make the very basis of your idea visual. Tacking visuals onto an idea that isn’t visual won’t work. Use visual humor—sight gags. Watch the old silent comedies, especially those with Charlie Chaplin and Laurel and Hardy. Watch The Three Stooges. Many cartoon writers are also artists, and they begin their thinking by drawing or doodling. The best animation is action, not talking heads. Even though Hanna-Barbera was known for its limited animation, Joe Barbera used to tell his artists that if he saw six frames of storyboard and the characters were still talking, the staff was in trouble. Start the story with action. Animation must be visual!

Time and space are important elements of animation. The laws of physics don’t apply. A character is squashed flat, and two seconds later he’s as good as new again. He can morph into someone else and do things that a real person couldn’t possibly do. Motion jokes are great! Wile E. Coyote hangs in midair. In animation the audience accepts data quickly. Viewers can register information in just a few frames. Timing is very important in animation, just as it is in comedy. The pace of gags is quick. Normally, there are more pages in an animation script than there are in a comparable, live-action script, partially because everything moves so fast.

Animation uses extremes—everything is exaggerated. Comedy is taken to its limits. Jokes that seem impossible in live-action are best, although with today’s special effects, there is little that can be done in animation that cannot be done in live-action film as well.

The Production Process

The production process is slightly different at different studios around the world. Even at a specific animation studio, each producer and director has his or her own preferences. Children’s cartoons are produced differently from prime-time animation because of the huge variation in budget. Television shows are not produced the same way as feature films. Direct-to-videos are something of a hybrid of the two. Independent films are made differently from films made at a large corporation. Shorts for the Internet may be completed by one person on a home computer, and games are something else altogether; 2D animation is produced differently from 3D; each country has its own twist on the process. However, because of the demands of the medium, there are similarities, and we can generalize. It’s important for writers to understand how animation is produced so they can write animation that is practical and actually works. Therefore, the production process follows in a general way.

The Script

Usually animation begins with a script. If there is no script, then there is at least some kind of idea in written form—an outline or treatment. In television a one-page written premise is usually submitted for each episode. When a premise is approved, it’s expanded into an outline, and the outline is then expanded into a full script. Some feature films and some of the shorter television cartoons may have no detailed script. Instead, creation takes place primarily during the storyboard process. Writers in the United States receive pay for their outlines and scripts, but premises are submitted on spec in hopes of getting an assignment. Each television series has a story editor who is in charge of this process. The story editor and the writers he hires may be freelancers rather than staff members. The show’s producers or directors in turn hire the story editor.

Producers and directors have approval rights on the finished script. Producer and director are terms with no precise and standard meaning in the United States, and they can be interchangeable or slightly different from studio to studio. Independent producers may deal more with financing and budgets, but producers at the major animation studios may be more directly involved with production. Higher executives at the production company often have script approval rights. Programming executives also have approval rights, as do network censors and any licensing or toy manufacturers that may be involved in the show. If this is a feature, financiers may have approval rights as well.

Recording

About the time the script is finalized, the project is cast. The actors may be given a separate actor’s script for recording. Sometimes they get character designs or a storyboard if they are ready in time. A voice director will probably direct. If this is a prime-time television project, then the director may hold a table read first, but usually there is no advanced rehearsal. At some studios the writer is welcome to attend the recording session. That is far from standard practice, however, and writers who do attend probably will have little or no input on the recording. Some studios still prefer to record all the actors at once for a television project, as if they were doing a radio play. However, each actor may be recorded separately. This is especially likely if the project is an animated feature. Individual recording sessions make it easier to schedule the actors, work with each actor, move the process along, and fine-tune the timing when it’s edited. Recording the actors together allows for interaction that is impossible to get any other way. Executives with approval rights have to approve casting and the final voice recording.

The directors usually work with a composer, who may be brought in early for a feature. Hiring might not be done until later in the process if this is a television show, although some directors bring in a composer early for TV as well.

The Storyboard

Storyboard artists take the script and create the first visualization of the story. Often these boards are still a little rough. In television and direct-to-video projects each major action and major pose is drawn within a frame representing the television screen. The dialogue and action are listed underneath each frame. Usually, an animatic or video of these frames is scanned or filmed from the board when it’s complete. This animatic, which includes any recorded sound, helps the director see the episode in the rough and helps in timing the cartoon. Executives must approve the final storyboard or animatic.

The storyboard process may take about a year for a feature. The script or treatment will undergo many changes as the visual development progresses. Artists sometimes work in groups on sequences, or a team of a writer and an artist may work together. The development team pitches sequences in meetings and receives feedback for changes. The director and other executives have final approval. Feature storyboard drawings are cleaned up and made into a flipbook. Finally the drawings are scanned or shot, the recorded and available sound is added, and the material is made into a story reel. Any necessary changes discovered during the making of the animatic or story reel are made on the storyboard. The building of the story reel is an ongoing process throughout production. Later breakdowns, then penciled animation, and finally completed animation will be substituted. This workbook of approved elements is usually scanned and available on staff computers and serves as an ongoing blueprint. For CGI features a 3D workbook shows characters in motion in space as well.

Slugging

The timing director sets the storyboard’s final timing, and the board is slugged. This does not mean that somebody gets violent and belts it with a left hook! Slugging is a stage when the overall production is timed out, and scenes are allotted a specific amount of time, measured in feet and frames. In television this information is added to the storyboard before it’s photocopied and handed out. An editor conforms the audiotape.

Character and Prop Design

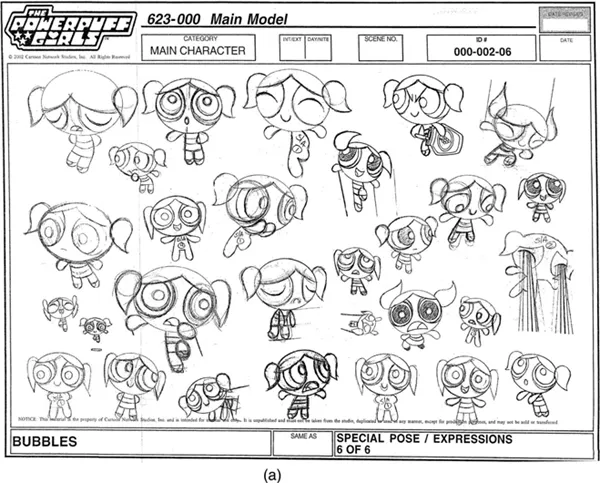

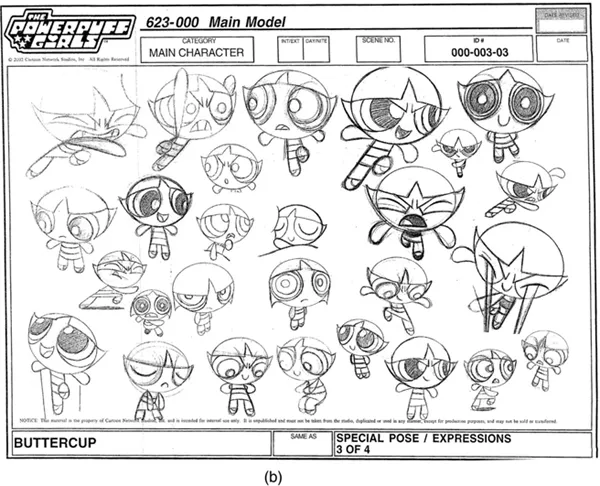

After the script has been approved, a copy goes to the production designer or art director. If the project is a television series, then the major and ongoing characters have already been designed and fine-tuned during development. The approved drawings, as seen from various angles, are compiled into the model sheets (see Figure 1.1). If the ongoing characters have a costume change in this TV episode or feature sequence, or new characters are needed, that must be considered. Each TV episode or feature sequence also requires props that have not been used before. Sometimes the same designers create new characters, costumes, and props; sometimes designers specialize and design either characters or props. New drawings are compiled into model sheets for each specific television episode. The drawings may be designed on paper or modeled in a computer. Approvals are required.

Figure 1.1 Bubbles (a) and Buttercup (b) from The Powerpuff Girls show off their acting skills on these model sheets.

The Powerpuff Girls and all related characters and elements are trademarks of Cartoon Network © 2004. A Time Warner Company. All rights reserved.

The Powerpuff Girls and all related characters and elements are trademarks of Cartoon Network © 2004. A Time Warner Company. All rights reserved.

Background Design

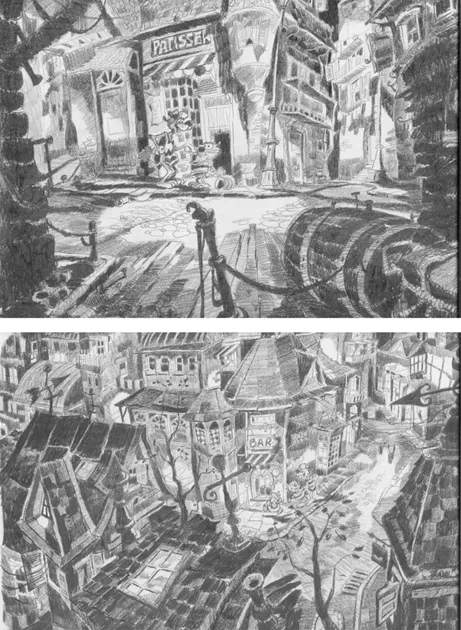

The production designer or a background designer is responsible for all location designs. In television or direct-to-video layout, artists will design these line drawings (layouts) from the roughs done by the storyboard artist (see Figure 1.2). Then a background painter will paint a few key backgrounds (especially those for establishing shots) and ship them overseas to be matched by other painters painting additional backgrounds. Very little animation production is done in the United States due to the high costs. In feature production the visual development artists may be working on both story and design at once, making many concept drawings before the final designs are chosen and refined for actual production. Background artists usually paint in the traditional way, but some or all elements can be painted digitally. Digital backgrounds can be changed more easily. Major designs require approval.

Figure 1.2 These drawings from Poncho Puma and His Gang are essentially background drawings with characters included for presentation and publicity purposes. Notice the use of perspective. Poncho Puma and His Gang © 1998 Alvaro A. Arce.

Color

Color stylists, who are supervised by the art director, set the color palette for a show. It’s important that they choose colors that not only look good together but that will make the characters stand out from the background. Different palettes may be needed for different lighting conditions, such as a wet look, shadowing, bright sunlight, and so on. If the project is CGI, texturing or surface color design is needed. Once again approvals are required.

Layout

Layouts are detailed renderings of all the storyboard drawings and breakdowns of some of the action between those drawings. These include drawings for each background underlay, overlay, the start and stop drawings for action for each character, and visual effects. Layout artists further refine each shot, setting camera angles and movements, composition, staging, and lighting. Drawings are made to the proper size and drawn on model (drawn properly). Key layout drawings may be done before a production is shipped overseas, with the remainder done by overseas artists. Or layout may be skipped, basically, by doing detailed drawings at the storyboard stage. Later these can be blown up to the correct size, and elements separated and used as layouts.

Exposure Sheets

The director or sheet timer fills out exposure sheets (X-sheets), using the information found on the audio track. These sheets will be a template or blueprint for the production, frame by frame and layer by layer. The recorded dialogue information is written out frame by frame for the animator, and the basic action from the storyboard is written in as well. If music is important, the beats on the click track are listed.

Animation

The animator receives the dialogue track of his section of the story, a storyboard or workbook that has been timed out, the model sheets, copies of the layouts, and X-sheets. There are boxes on the X-sheets for the animator to fill in with the details, layer by layer, as the animation is being planned. Animation paper, as well as the paper used by the layout artists and background artists, has a series of holes for pegs so that it can be lined up correctly for a camera. For an animated feature, animation pencil tests may be made prior to principal animation to test the gags and the animation. In television and direct-to-video projects, key animators may animate the more important action before it is sent overseas for the major animation to be completed. Animators might be cast to animate certain characters, or they may be assigned certain sequences.

Clean-up artists or assistant animators clean up the rough animation poses drawn by the animator and sketch the key action in between. A breakdown artist or inbetweener may be responsible for the easier poses between those. Visual effects animators animate elements like fire, water, and props. For a feature production where drawings are ani...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction and User’s Manual

- 1. Introduction to Animation

- 2. The History of Animation

- 3. Finding Ideas

- 4. Human Development

- 5. Developing Characters

- 6. Development and the Animation Bible

- 7. Basic Animation Writing Structure

- 8. The Premise

- 9. The Outline

- 10. Storyboard for Writers

- 11. The Scene

- 12. Animation Comedy and Gag Writing

- 13. Dialogue

- 14. The Script

- 15. Editing and Rewriting

- 16. The Animated Feature

- 17. Types of Animation and Other Animation Media

- 18. Marketing

- 19. The Pitch

- 20. Agents, Networking, and Finding Work

- 21. Children’s Media

- Glossary

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Animation Writing and Development by Jean Wright,Jean Ann Wright in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Computer Science & Digital Media. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.