![]()

1 Why Evaluate Schools?

Why evaluate schools? Why not leave them alone to do what they do best, to get on with the business of teaching and learning?

The answer is simple. There is no alternative. For as long as we have had schools we have evaluated them. We have not always done it well or systematically. It has often been intuitive, off the cuff, a matter of hearsay and reputation. And what have often been widely regarded as good schools have benefited from mythology and mystique. Evaluating the quality of schools is not just the researcher’s province. It has always been an element in people’s everyday vocabulary. Whatever the nature of their judgements, the quality of schools has for many years been a matter of concern to most parents, some of whom put their child’s name down for ‘a good school’ even before their child is born. Virtually every parent wants his or her child to have ‘a good education’ and that is often equated with sending him or her to a ‘good’ school.

But what lies beneath the comment ‘It’s a good school’? What meanings are attached to that judgement, and what differing forms do meanings take when pronounced by a politician, a journalist, an inspector, a pupil, a researcher, or a parent recommending their own child’s school to a neighbour? And what is the difference between a ‘good’ school and an ‘effective’ one?

How Good is Effectiveness?

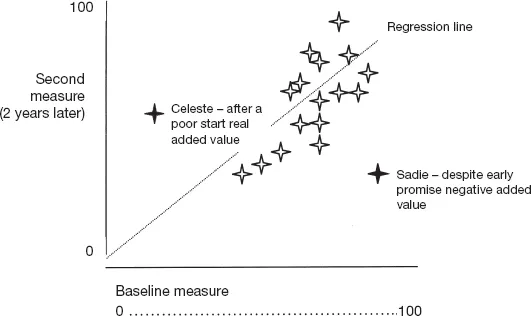

The term ‘effective’ has passed imperceptibly into our everyday vocabulary and into policy dialogue. It is often used synonymously with ‘good’, so concealing a multitude of possible meanings. For the purist researcher, effectiveness is a measurement of progress over and above what might have been predicted from pupils’ background characteristics and prior attainment. That is what is commonly referred to as the ‘added value’ which is the mark of an effective school as against a ‘good’ one. By this definition, a school is effective when it surpasses the predictions about the future success of its pupils. The ‘value’ that is added is normally a reference to extra unpredicted attainment that exceeded the forecast of prior attainment or baseline measurement. It is what appears ‘above the line’ on any graph which compares attainment at two points in time (as in Figure 1.1.).

Figure 1.1 Illustrating value-added attainment

A decade or so ago teachers in the United Kingdom might have been baffled by such statistical wizardry, but third-millennium schools have had to familiarise themselves with this way of thinking about their work and this way of measuring their success. However, most teachers, most researchers and policy-makers too, regard such a measure of success as only partial and potentially misleading. It is hard to see how any school could be called effective without broader measures of achievement such as improved attitudes, motivation, raised esteem and difficult-to-measure skills such as learning to learn. The more we stretch the definition of effectiveness, however, the more difficult it becomes to see the difference between the ‘good’ and the ‘effective’, and it is difficult to see how an effective school could not be good and a good school not effective.

Good schools and effective schools are, ultimately, a matter of perspective. They depend on the criteria we use for our judgement, however implicit or explicit these criteria are. All judgements are made in a context, within a culture and within a linguistic convention. All our evaluations subsume clusters of value judgements, beliefs and opinions. Sometimes these are so deeply embedded in our thinking and discourse that they are not open to question. Some value judgements are taken as so fundamental to human life and well-being that they are beyond question. For example, no one is prepared to contest that learning is a good thing, that age is a significant factor in deciding what children should and shouldn’t know, or that children’s behaviour and beliefs should be shaped by adults. In other words, there is a moral base on which school education is allowed to rest and that moral base is a virtually universal one.

What is Good about Good Schools?

Going beyond these unquestioned taken-as-read value judgements there is a fairly solid core of agreement on what is good about schools. Irrespective of culture we prefer orderly to disorderly schools, well-managed to badly-managed schools, schools in which pupils show progress over time, schools in which teachers monitor and assess how well their pupils are doing. We believe that parents are necessary and valued co-educators and that children learn best when there is some form of bridge between home and school learning. We believe that learning has a social dimension and that it is good for children to cooperate with and learn from one another.

These are generally undisputed characteristics, or benchmarks, of good schools. They are ones which we continually monitor and measure in the day-to-day life of schools and classrooms. We do this mostly in a subjective or intuitive fashion, only becoming concerned when these basic tenets are breached in some way. Our consensus on common values might progress quite a distance before we begin to diverge in our judgements, but we sooner or later do reach a point where our opinions begin to become more contested. These differences become progressively more acute across different national contexts, cultures and ethnic languages. Yet even beneath a common language and a common national culture lie some quite different understandings of the emphasis and priority that ought to be given to some values as against others. We reach a point too where we begin to dissect the common language and discover that it sometimes conceals more than it reveals.

Virtually everyone wants schools in which children respect their teachers, but what does ‘respect’ mean? Everyone believes that pupils should behave well, but can they agree on what constitutes ‘good’ behaviour? Order is inherently preferable to disorder, but how do we distinguish one from the other? Is someone’s disorder another’s order? Highly interactive noisy classrooms may be underpinned by order which is not apparent at first sight and a highly ordered classroom may conceal beneath its surface slow educational death.

What may have appeared at first sight to be simple and common-sensical turns out to be so complex that it is tempting is to abandon systematic evaluation and trust to the sound professional judgement of each individual teacher or headteacher. However, it is the very complexity of what makes for good, and less good, schools that makes evaluation compelling, significant and worth pursuing.

The ‘pursuing’ of evaluation has, historically, come from three main directions:

- from the top down, driven by political pressures, nationally and internationally, to assure quality and deliver value for money;

- from the bottom up, stimulated by schools seeking strategies and tools for self-improvement;

- from sideways on, from researchers and commentators, in particular school effectiveness research which has, over three decades, pursued inquiry into what makes schools effective and what it is that helps schools improve.

These three strands of development are virtually impossible to disentangle in simple cause-and-effect terms. Researchers could not have produced their findings without the insights and collaboration of teachers. Policy-makers relied on researchers to lend authority to their pronouncements. Research and policy fed back into school and classroom practice. And, as in the natural order of things, the implicit becomes gradually more explicit, the informal becomes formal and evaluation is discovered, and rediscovered, from generation to generation.

The Germans have a word, ‘Zeitgeist’, to describe a climate of ideas whose time has come. The need for better, more systematic, evaluation of schools is a third millennium global zeitgeist. It finds a common meeting ground of schools and authorities, policy-makers and politicians, researchers and academics. There is an emerging consensus among these various groups and across nations that we want to get better at evaluation because it is good for pupils, for parents and for teachers because without it what is learned is simply a matter of hunch, guesswork and opinion.

Beneath this happy consensus, however, lie some deeply contested issues. Evaluation is a good thing, but who should do it? We all want better evaluation, but what should be evaluated? Evaluation is necessary, but when and how should it be carried out? Evaluation is beneficial, but who is it for?

Who Should Evaluate?

A decade or so ago we might have answered this with a simple retort – Her Majesty’s Inspectors. Or perhaps, we might have entrusted this to local education authority inspectors or advisers. In 2002 a more common answer to the question would be: ‘Schools themselves’. There does, however, appear to be an emerging consensus that the most satisfactory answer to the question is both. Both internal and external evaluation have complementary roles to play. (This is the theme we explore in chapter 2.)

What Should We Evaluate?

Evaluating schools has been a major thrust of policy in the last two decades in the UK. It has drawn heavily on the work of school-effectiveness researchers and their three-decade-long pursuit of the question ‘What makes an effective school?’ with assumptions built into that question that have been increasingly challenged by others from different fields of inquiry (see, for example, Thrupp, 1999).

Effectiveness research has taken the school as the unit of analysis, working on the assumption that a school as an entity makes a critical difference, and that going to school A as against school B is a prime determinant of life chances. Inspection and reporting in all UK countries has similarly taken the school as the unit of analysis and reported publicly on the quality of the school, its ethos, leadership, shared culture of learning and teaching. Evaluation at whole-school level is less taken for granted in other cultures, however. Countries such as France and Belgium have tended to focus inspection on individual classrooms and individual teachers. In many German states, Swiss cantons or Danish communes, teachers have enjoyed a considerable measure of individual autonomy, neither seeing the need to know what other teachers were doing in their classrooms nor accepting the necessity of senior management observing or evaluating the quality of their teaching.

While the school effect has been reported in highly optimistic terms – ‘Schools can make a difference’ (Brookover et al., 1979), ‘School matters’ (Rutter, Mortimore et al., 1979) – researchers have come progressively to the recognition that schools make less of a difference than teachers. So in recent years effectiveness researchers have turned their attention much more to the internal characteristics of schools, to departments and classrooms as the focal point for what differentiates success from failure. Unsurprising as such a refocusing might be, the implications are far-reaching. It means that if we are to get a true and faithful measure of effectiveness our primary concern has to be with what happens in individual classrooms, with individual teachers and with individual learners.

This refocusing more on what happens in classrooms should not, however, ignore the wider focus on school culture. It is not a matter of either or: school or classroom, management or teachers, teaching or learning. Measuring effectiveness means sharpening our thinking as to where we should give most attention and invest our energies at any given time and in light of the priorities we pursue. And as we get better at it we recognize that in good schools the boundaries between different levels become so blurred that they defy even the most inventive of statistical techniques.

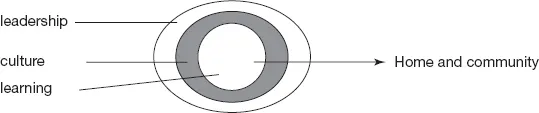

Research and school experience point towards three main levels, which may be illustrated as in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2 Circles of evaluation

At the centre of our model we have to put pupil learning, because this is unarguably the most central and significant purpose of school education. At the second level is culture, that is the climate and conditions which not only enable pupil learning to flourish but also sustain staff learning. The third level is leadership, that is the direction and driving force which creates and maintains the culture. Taken together these three points of focus provide the essential constituents of the school as a learning community.

There is, however, a critical missing ingredient, indicated by the arrow which points out from the school to the home and community. None of what takes place at any of these three levels can be evaluated in any meaningful sense without reference to the wider context in which they operate. Leadership must be outward-looking and responsive to the needs and expectations of both the local and the wider community. Culture is not merely something fabricated within the school walls but is brought in by pupils and teachers, a product of past histories and future hopes. Learning is as much a home and community matter as a school matter, and how children learn outside school should be as critical a focus of evaluation as what they learn inside classrooms.

In deciding what to evaluate there is an irresistible temptation to measure what is easiest and most accessible to measurement. Measurement of pupil attainment is unambiguously concrete and appealing because over a century and more we have honed the instruments for assessing attainment and for a century and more these pupil-attainment measures have provided benchmarks for teachers and those who had an interest in monitoring and comparing teacher effectiveness.

Numbers of words correctly spelt, percentage of correct answers on an arithmetic test, words decoded correctly on a reading test, or terms translated correctly from French to English provide fairly unambiguous performance measures. This process is normally described as ‘assessment’ because it measures individual attainment, but these measures have served evaluation purposes too because they provide evidence on the performance of a group – an ethnic group, boys and girls, a class, a school, an authority or a nation. So, we have volumes of data on the attainment of boys as against girls, the underperformance of certain ethnic groups and, in addition, large-scale international studies such as the Third International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) which aggregates pupil-attainment scores to national level in order to compare how different countries perform.

In the process evaluation has become so clearly associated with assessment that the terms now tend to be used interchangeably. The distinction is, however, critical. If the evaluation of national, school or teacher effects rests on assessment of pupil performance we must be clear about the assumptions and limitations of that view.

Evaluation and Assessment – Making the Distinction

The distinction between assessment and evaluation may be illustrated by taking the example of the individual pupil. A pupil may be asked to assess for himself a recently completed piece of work, perhaps giving it a grade or applying a set of given criteria. In this way the pupil shares with the teacher in the assessment process. However, if the pupil is asked to engage in evaluation it requires taking a further step back, moving outside the situation, addressing questions such as these:

- Was the experience worthwhile?

- Were the criteria for assessment the right ones?

- What did I learn from that process?

- What might I do next time to improve?

- How am I developing as an eff...